Abenaki Maple Ceremonies: Honoring the First Sweet Water of Spring

As the late winter chill begins to recede, yielding to the subtle warmth of early spring, a profound transformation stirs in the forests of what is now known as New England and Eastern Canada. This isn’t merely a shift in seasons; for the Abenaki people, it marks the sacred return of Sokanon, the Sugar Moon, and the awakening of the maple trees. It is a time for profound gratitude, renewal, and the ancient practice of honoring the Sipask – the first sweet water of spring – through ceremonies that resonate with thousands of years of cultural memory and ecological wisdom.

The Abenaki Maple Ceremony is far more than a simple harvest; it is a meticulously observed ritual of thanksgiving, a spiritual communion with the land, and a powerful affirmation of their enduring connection to the natural world. It predates European contact by millennia, rooted in a worldview that perceives all living things as relatives and resources as gifts to be used with respect and reciprocity. The maple tree, Sipaskw, is not just a source of food; it is a life-giver, a teacher, and a central figure in their creation stories.

One of the most cherished Abenaki legends tells of Gluskabe, the culture hero, and how he made the maple trees give forth their sweet sap. Originally, the legend recounts, maple trees produced thick, pure syrup that flowed freely. People did not have to work, and this abundance made them lazy, neglecting their other responsibilities and their spiritual connection to the Creator. Seeing this, Gluskabe, in his wisdom, diluted the syrup with water, transforming it into sap that required considerable effort – tapping, collecting, and boiling – to yield its sweet essence. This act instilled in the people the values of hard work, gratitude, and community cooperation, ensuring they would always remember the gift and the labor required to receive it. "It taught us the value of effort, of working together, and of never taking the gifts of the Creator for granted," explains an Abenaki elder, his voice imbued with generations of wisdom. "The sweetness of the maple became a reward for our diligence, a reminder of the balance Gluskabe brought to our lives."

The ceremony typically begins not with the tapping, but with a deep spiritual preparation. It is a time of prayer and introspection, acknowledging the generosity of the Creator and the spirit of the maple tree. Before the first tap is ever driven, an offering is made, often tobacco, placed at the base of a chosen maple. This act is a humble request for permission, an expression of gratitude, and a promise to use the sap respectfully. "We ask the tree for its gift," states another Abenaki community member, describing the ritual. "We tell it we will use its water to nourish our families, to heal, and to give thanks. It’s a conversation, a bond."

The tapping process itself is a carefully choreographed dance between human hands and the ancient trees. Historically, the Abenaki used methods that are remarkably similar to those employed by contemporary "sugarmakers," albeit with tools crafted from the forest. Birch bark containers, hollowed-out logs, and later, wooden spiles were used to collect the flowing sap. Stone tools and hot stones were employed to boil the sap down in birch bark or clay vessels. The efficiency and ingenuity of these pre-contact practices are a testament to their deep empirical knowledge of the forest and its cycles. Archaeological findings in the Northeast have unearthed evidence of maple sugaring dating back over 3,000 years, confirming the ancient roots of this tradition. These sites often show concentrations of fire-cracked rock and pottery shards, indicating long-term sap processing locations.

Central to the ceremony is the collective effort. Maple sugaring was, and remains, a communal activity. Families, clans, and entire villages would gather in the sugarbush, or Sipaskwan, sharing the labor of tapping, collecting, and boiling. The air would fill with the sweet, earthy scent of woodsmoke and evaporating sap, a sensory signature of spring’s arrival. Songs and stories would accompany the work, particularly as the sap slowly transformed into syrup, then into sugar cakes or granular sugar, a vital sweetener and preservative for the year ahead. These gatherings reinforced social bonds, provided opportunities for elders to pass down knowledge to younger generations, and ensured the continuity of cultural practices.

The Abenaki worldview emphasizes a reciprocal relationship with nature. When they take, they also give back. This principle extends to their maple practices. They understand the importance of not over-tapping a tree, ensuring its health and continued productivity for future seasons and future generations. Only healthy, mature trees are tapped, and care is taken to rotate tap holes and to avoid causing undue stress to the tree. This inherent sustainability is not a modern concept for the Abenaki; it is an intrinsic part of their traditional ecological knowledge, a testament to a wisdom that recognizes the interconnectedness of all life. "We don’t just take," says a tribal environmentalist. "We manage. We live with the forest, not just in it. Our ancestors taught us that if you respect the land, it will always provide."

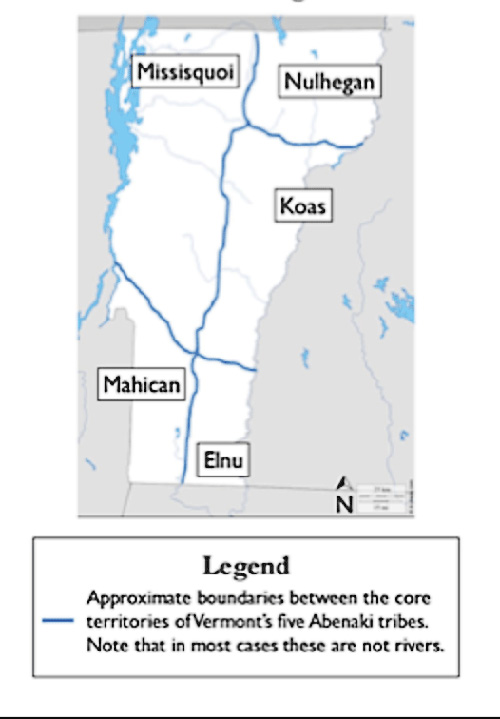

In contemporary times, the Abenaki Maple Ceremonies continue to be a vibrant expression of cultural identity and resilience. While the tools may have evolved to include metal spiles and evaporators, the spirit of the ceremony remains unchanged. Abenaki communities across their traditional territories, from Vermont to Quebec, hold annual maple gatherings. These events often include traditional drumming, singing, storytelling, and shared meals featuring maple-infused dishes. They serve as crucial opportunities for cultural revitalization, particularly for younger Abenaki who may be growing up in urban environments, disconnected from the ancestral lands.

The act of sharing the first syrup of the season is particularly significant. It symbolizes sharing abundance, gratitude, and the enduring strength of the community. It is a time for feasting, for reconnecting with family and friends, and for celebrating the renewed life that spring brings. The taste of that first, freshly boiled maple syrup is not merely sweet; it carries the essence of the forest, the labor of hands, and the prayers of a people deeply rooted in their heritage. It is a taste of continuity, a flavor of survival.

Beyond the immediate community, the Abenaki Maple Ceremonies offer profound lessons for the wider world. In an era of increasing environmental concern and a growing disconnect from natural cycles, these ancient practices highlight the importance of respectful stewardship, sustainable harvesting, and the spiritual dimension of our relationship with the Earth. They remind us that food is not just sustenance for the body, but also for the spirit, and that true abundance comes from living in harmony with the natural world, rather than attempting to dominate it.

The "First Sweet Water of Spring" is more than just sap; it is a potent symbol of life, resilience, and the enduring wisdom of the Abenaki people. Their maple ceremonies are not relics of the past but living traditions, vibrant testaments to a culture that continues to honor the gifts of the Creator, sustain its people, and remind us all of the profound sweetness found in gratitude and respect for the earth. As the sap begins to run again this spring, carrying the promise of new life, the Abenaki will once again stand with the trees, offering their prayers and ensuring that the ancient bond with the maple, and all that it represents, continues to flow for generations to come.