The Arctic, a landscape of breathtaking beauty and formidable challenges, has historically demanded unparalleled ingenuity from its inhabitants. Among their most remarkable innovations stands the traditional Eskimo kayak, or qajaq as it is known in many Inuit dialects. Far more than just a boat, the qajaq was a vital tool for survival, a hunter’s indispensable companion, and a testament to centuries of accumulated knowledge and craftsmanship.

This comprehensive guide delves into the intricate world of traditional Eskimo kayak construction, exploring the materials, techniques, and profound cultural significance that shaped these extraordinary vessels. From the selection of driftwood to the meticulous stitching of seal skin, every step in the process was a blend of practicality, skill, and a deep understanding of the harsh Arctic environment.

For thousands of years, the indigenous peoples of the Arctic regions – including the Inuit, Yup’ik, and Aleut – relied heavily on the sea for sustenance. Hunting marine mammals such as seals, walruses, and even whales was critical for their survival, providing food, blubber for fuel, and materials for clothing and tools. The kayak emerged as the perfect solution for silent, swift, and efficient hunting in icy waters.

The design of the traditional qajaq was not accidental; it was the result of continuous refinement over millennia, adapting to specific regional needs and hunting practices. Its low profile, narrow beam, and exceptional maneuverability made it ideal for stealthily approaching prey and navigating treacherous coastal waters and ice floes.

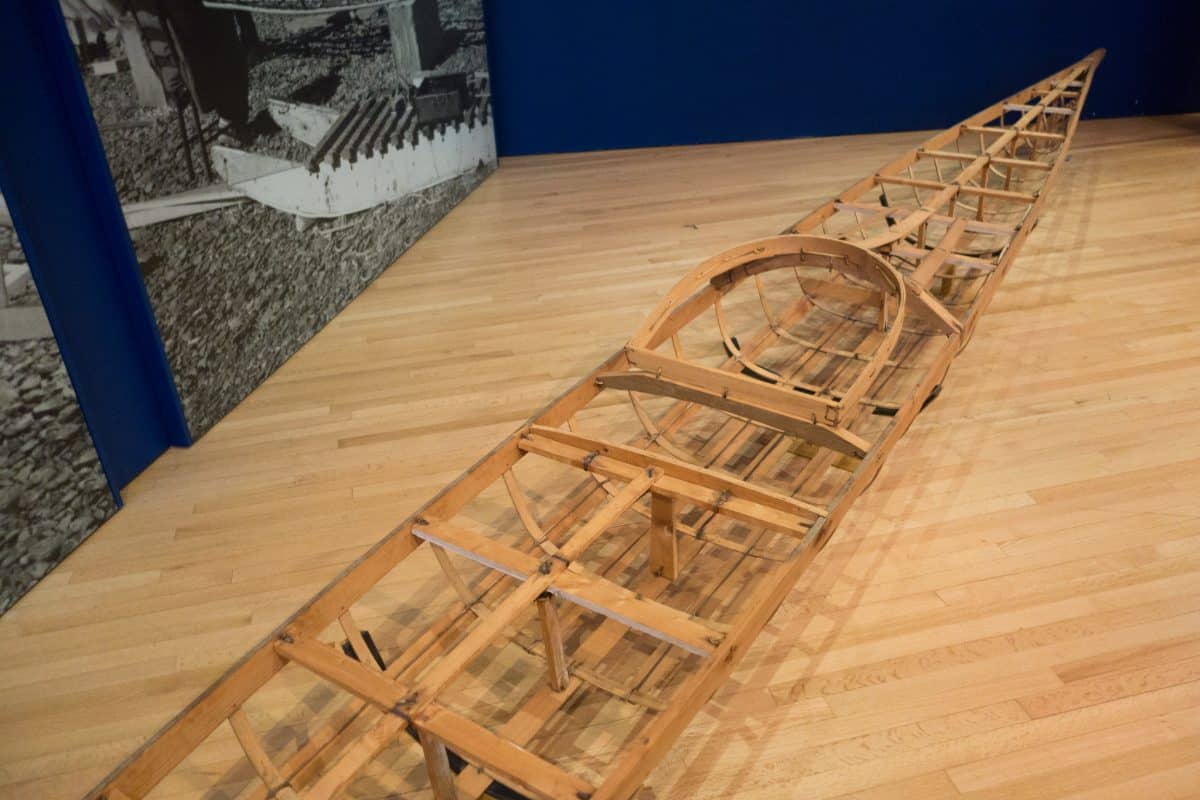

At its core, the traditional Eskimo kayak is a ‘skin-on-frame’ vessel. This construction method involves building a lightweight, flexible wooden skeleton and then covering it with a durable, waterproof skin. This approach offered several advantages, including portability, ease of repair, and the ability to absorb impact without catastrophic failure, a crucial feature in icy conditions.

The most critical component of any qajaq was its internal framework, the skeleton. Finding suitable materials in the treeless Arctic was a challenge. Driftwood, carried by ocean currents from distant forests, was the primary source of timber. This precious resource was carefully collected, often stored for years, and expertly chosen for specific parts of the kayak.

Beyond driftwood, builders ingeniously utilized other available materials. Bone, particularly from whales or caribou, and antler were often used for smaller components, joints, or reinforcing critical areas. These materials provided strength and durability where wood might be scarce or less suitable.

The skeleton typically consisted of several key elements: a long, slender keel forming the backbone, numerous delicate ribs that defined the hull’s shape, and a series of longitudinal stringers running parallel to the keel, providing rigidity and attaching the ribs. Deck beams created the top structure, supporting the deck and the all-important cockpit coaming.

The joining of these skeletal components was a masterpiece of pre-industrial engineering. Rather than nails or screws, which were unavailable, builders used intricate lashing techniques. Sinew – strong fibers made from animal tendons – was the primary lashing material, often combined with wooden pegs. These lashings allowed for a degree of flex, making the kayak more resilient to stress and impact.

Once the skeleton was complete, the next crucial step was applying the skin. Traditionally, seal skin was the material of choice due to its strength, flexibility, and natural waterproofing properties. Occasionally, caribou hide was used, though it was generally thicker and less ideally suited for the hull.

Preparing the seal skin was a labor-intensive process, often performed by women. The skins were carefully cleaned, dehaired, and then stretched and dried. Multiple skins, typically three to five depending on the kayak’s size, were meticulously stitched together to form a seamless, watertight covering.

The stitching itself was an art. Using a bone awl and sinew thread, the seams were created with a special waterproof stitch that prevented water ingress. After stitching, the entire skin was often treated with seal oil or animal fat, which further enhanced its waterproofing and preserved its flexibility, creating a truly impermeable barrier against the cold Arctic waters.

The traditional Eskimo kayak was not a monolithic design; significant regional variations existed, reflecting local hunting needs, available resources, and cultural preferences. These differences are a testament to the adaptive genius of Arctic peoples.

The East Greenlandic kayak, for instance, is renowned for its sleek, narrow, and extremely fast design. Its sharp chines and low volume were optimized for speed and agility in open water, often used for hunting seals with harpoons. This design demanded exceptional skill from the paddler.

In contrast, the West Greenlandic kayak often featured a slightly wider beam and more rounded hull, offering greater stability. While still very agile, it provided a more forgiving platform for diverse hunting activities and navigating coastal areas with varying conditions.

The Aleut baidarka, from the Aleutian Islands, stands out with its unique multi-cockpit designs, sometimes accommodating two or three paddlers. Characterized by a distinctive bifurcated bow and stern (split ends), the baidarka was known for its exceptional speed and seaworthiness in the often tempestuous waters of the North Pacific.

The tools used in traditional kayak construction were as ingenious as the kayaks themselves. Builders relied on locally sourced materials, crafting specialized instruments: adzes for shaping wood, various types of knives (often with stone or bone blades) for cutting and carving, and bone awls for piercing holes in hide for stitching. The mastery of these simple tools to create such complex structures is truly remarkable.

Building a qajaq was more than a technical task; it was a deeply cultural and spiritual endeavor. The knowledge was passed down through generations, often from father to son, emphasizing patience, precision, and a profound respect for the materials and the environment. Each kayak was custom-built to fit its paddler, becoming an extension of their body and will.

Upon completion, the qajaq was immediately put to use. It allowed hunters to quietly stalk seals, navigate through ice, and retrieve their catch. The intimate connection between the hunter and their vessel was paramount; a well-built kayak could mean the difference between a successful hunt and starvation.

Maintenance was an ongoing process. The skin, though durable, required periodic re-oiling and minor repairs to ensure its watertight integrity. Small tears could be patched, and lashings tightened. The flexibility of the skin-on-frame design made minor repairs relatively straightforward, extending the life of these essential craft.

Today, the traditional Eskimo kayak continues to inspire. Modern skin-on-frame builders around the world study and replicate these ancient designs, appreciating their efficiency, beauty, and connection to a rich cultural heritage. The principles of lightweight construction, flexibility, and hydrodynamic efficiency found in the qajaq are still relevant in contemporary paddle craft design.

The revival of traditional kayaking, often referred to as ‘Greenland style paddling,’ has led to a renewed interest in the qajaq’s unique characteristics and the skills required to paddle them. Enthusiasts learn traditional rolls, sculling strokes, and the nuanced handling of these highly responsive boats, honoring the legacy of their original builders.

What is a traditional Eskimo kayak made of? Primarily, the skeleton is constructed from driftwood, supplemented by bone or antler, and lashed together with sinew. The outer covering is typically waterproofed seal skin.

How were Eskimo kayaks built? They were built using a ‘skin-on-frame’ method. First, a flexible skeleton of wood, bone, and antler was assembled using intricate sinew lashings. Then, prepared and stitched seal skins were stretched over the frame and waterproofed with animal fats.

What is the name of the Eskimo kayak? The indigenous term frequently used is qajaq (pronounced ‘kai-yak’), which is the origin of the English word ‘kayak.’ The Aleut people referred to their similar craft as a baidarka.

How did Eskimos waterproof their kayaks? After the seal skins were stitched together and stretched over the frame, they were thoroughly treated and sealed with animal fats, such as seal oil, which rendered them highly waterproof and helped preserve the material.

Why did Eskimos use kayaks? Kayaks were essential for hunting marine mammals like seals, walruses, and whales, providing a stealthy, fast, and stable platform for navigating Arctic waters. They were also crucial for travel and transport in their coastal environments.

The traditional Eskimo kayak is more than just a historical artifact; it is a living legacy of human ingenuity, adaptability, and profound respect for the natural world. Its elegant design and sophisticated construction methods speak volumes about the deep knowledge and practical skills possessed by the indigenous peoples of the Arctic.

From the careful selection of materials in a resource-scarce environment to the meticulous craftsmanship of its frame and skin, every aspect of the qajaq’s creation was purposeful. It represents a harmonious blend of form and function, a vessel perfectly suited to its challenging domain.

Understanding traditional Eskimo kayak construction offers a window into a culture that thrived by mastering its environment, not by conquering it. It reminds us of the power of observation, innovation, and the enduring human spirit to create tools that enable survival and foster a deep connection with the natural world.

In conclusion, the traditional Eskimo kayak, or qajaq, stands as an enduring symbol of Arctic craftsmanship. Its skin-on-frame construction, utilization of natural materials like driftwood and seal skin, and ingenious lashing techniques created a vessel perfectly adapted for hunting and travel in the challenging polar environment. This remarkable legacy continues to inspire paddlers and builders worldwide, a testament to its timeless design and the profound wisdom of its creators.