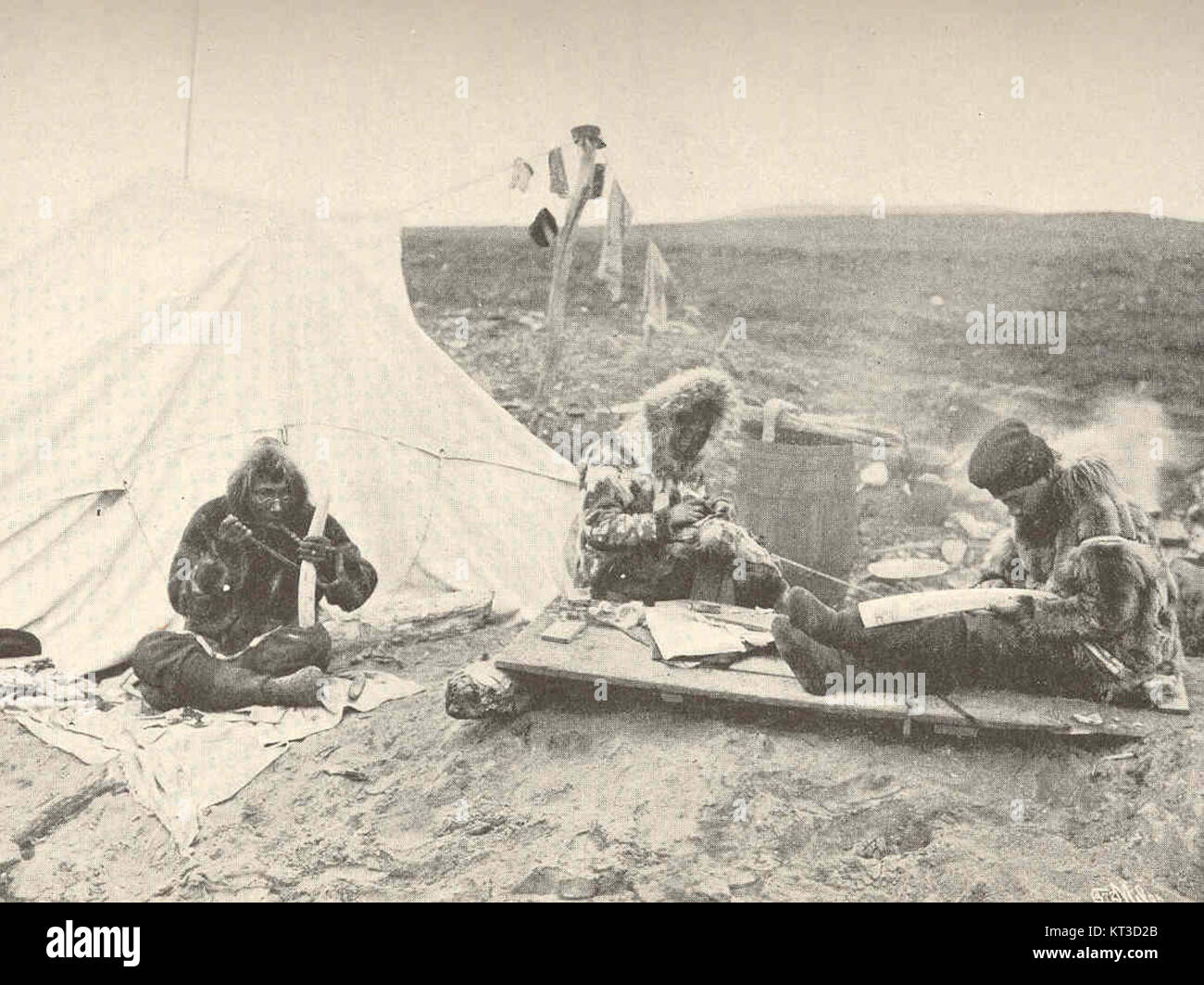

The Arctic, a landscape of breathtaking beauty and unforgiving conditions, has long tested the limits of human endurance. For millennia, Indigenous peoples of the Arctic, often broadly referred to as Eskimo or Inuit, have not merely survived but thrived in this challenging environment, largely due to their profound understanding of the land, its resources, and their ingenious clothing.

Traditional Eskimo clothing craftsmanship is a testament to human innovation, a sophisticated system of design and fabrication honed over thousands of years. It represents far more than mere garments; it is a vital survival technology, a cultural expression, and an art form.

This comprehensive guide delves into the intricate world of Arctic apparel, exploring the materials, techniques, and cultural significance that define this remarkable heritage. We will uncover how these master craftspeople transformed raw resources into functional masterpieces that offered unparalleled protection against the frigid elements.

The Indispensable Materials of Arctic Survival

The foundation of effective Arctic clothing lies in the careful selection and preparation of natural materials. Every component, from the animal hides to the sinew used for stitching, was chosen for its specific properties – insulation, durability, water resistance, and flexibility.

Caribou Hide: The Ultimate Insulator. Caribou (reindeer) hide was a primary material, particularly prized for its exceptional insulating properties. The hollow hairs of the caribou trap air, creating a dense, warm layer that effectively keeps the wearer warm even in extreme cold.

Sealskin: Waterproof and Durable. Sealskin, with its natural oils and dense fur, offered excellent water resistance and durability. It was often used for outer layers, especially for hunting and travel on ice and water, providing a crucial barrier against wetness.

Polar Bear Fur: Elite Warmth for Specialized Garments. Less common but highly valued, polar bear fur provided unparalleled warmth and was often reserved for specific garments or trims due to the difficulty and danger of hunting polar bears. Its dense undercoat and long guard hairs are incredibly insulating.

Bird Skins and Feathers: Lightweight Warmth. For lighter, inner layers or specialized items, bird skins, particularly eider duck, were used. The down and feathers provided excellent, lightweight insulation, often used in conjunction with other furs.

Animal Sinew: Strong and Biodegradable Thread. Sinew, extracted from the tendons of animals like caribou or seal, served as the primary sewing thread. When dried and split, it was incredibly strong and, crucially, would swell when wet, creating a naturally waterproof seam.

Gut Skin: The Transparent and Watertight Marvel. The intestines of seals or whales, meticulously cleaned and prepared, were stretched into thin, translucent sheets. These ‘gut skin’ garments, known as kamleikas, were remarkably lightweight, windproof, and waterproof, ideal for kayak hunting or rain protection.

Traditional Tools: Crafting with Precision

The creation of these complex garments required specialized tools, often made from bone, stone, or antler. These tools were simple yet highly effective, reflecting a deep understanding of material properties and ergonomic design.

The Ulu: The Versatile Arctic Knife. The ulu, a crescent-shaped knife with a handle in the center, was indispensable. Used for skinning, cutting, and preparing hides, its unique design allowed for precise, rocking cuts, making it superior to straight-bladed knives for these tasks.

Bone Needles: Durable and Effective. Needles crafted from bone or ivory were essential for stitching. Their strength allowed them to pierce tough hides, and their smooth surfaces prevented snagging the sinew thread.

Scrapers and Softeners: Preparing the Hides. Various scrapers, often made from bone or stone, were used to remove flesh and fat from hides. Specialized tools, sometimes combined with chewing, were then used to soften the hides, making them pliable for sewing.

Ingenious Crafting Techniques: Beyond Simple Sewing

The true genius of Eskimo clothing lies not just in the materials but in the sophisticated techniques employed to assemble them. These methods were developed to address the unique challenges of the Arctic climate.

Skin Preparation: The Foundation of Quality. Hides underwent extensive preparation, including scraping, drying, and often chewing by women to soften them. This meticulous process was crucial for creating durable, flexible, and insulating materials.

Patterning for Optimal Fit and Function. Garments were cut to specific patterns that maximized warmth, allowed for freedom of movement, and minimized seams. The patterns often incorporated ample room for layering and ease of donning.

Waterproof Seams: A Critical Innovation. For outer garments, especially those made from sealskin, waterproof seams were paramount. This was achieved through a unique double-stitch technique, where two rows of stitches were made, with the sinew swelling when wet to seal the holes.

Layering for Thermoregulation. Arctic clothing was typically designed in layers. An inner layer of fur with the hair facing inward provided direct warmth, while an outer layer with the hair facing outward offered additional insulation and protection from wind and snow. The air trapped between layers was key to warmth.

Key Garments: Designed for Specific Needs

Each piece of traditional Arctic clothing served a specific purpose, meticulously designed for maximum efficiency and protection.

The Parka (Qulittaq/Amauti): The Iconic Outerwear. The parka, known by various names such as qulittaq or amauti (for women, with a large pouch for carrying a baby), is the quintessential Arctic outer garment. Hooded and often made from caribou or sealskin, it provided full-body warmth.

Kamiks: The Ultimate Arctic Boots. Kamiks are traditional boots, typically made from sealskin or caribou hide, often with a waterproof sole and sometimes lined with fur or grass for added insulation. They were designed to be lightweight, flexible, and provide excellent traction on ice and snow.

Pants and Mittens: Essential Extremity Protection. Trousers, often made from caribou or polar bear fur, protected the legs. Mittens (pualuk), frequently made from sealskin with fur lining, were crucial for preventing frostbite on hands, proving more effective than gloves in extreme cold.

Cultural Significance and Enduring Legacy

Beyond their practical function, traditional Eskimo garments held deep cultural significance. They were often adorned with intricate patterns, fringe, and decorative elements, reflecting the wearer’s identity, status, and artistic expression.

The creation of clothing was a communal effort, particularly among women, who passed down their extensive knowledge of tanning, cutting, and sewing techniques through generations. This collective wisdom ensured the survival and well-being of the entire community.

Today, the legacy of Eskimo clothing craftsmanship continues to inspire. Modern outdoor apparel companies draw lessons from these ancient designs, incorporating principles of layering, material selection, and ergonomic fit into their high-performance gear.

Preservation efforts are vital to maintaining this rich heritage. Indigenous communities are actively working to revitalize traditional skills, ensuring that younger generations learn the intricate art of crafting these essential garments, connecting them to their ancestors and cultural identity.

The profound ingenuity of Arctic clothing craftsmanship stands as a powerful reminder of humanity’s ability to adapt, innovate, and create beauty in the face of nature’s most extreme challenges. It is a legacy of survival, artistry, and deep respect for the natural world.

People Also Ask: Common Questions About Eskimo Clothing

What is traditional Inuit clothing made of? Traditional Inuit clothing is primarily made from the hides and furs of Arctic animals such as caribou, seal, polar bear, and various bird skins, along with sinew for stitching and occasionally gut skin for waterproof layers.

How did Inuit make their clothes waterproof? Inuit crafted waterproof garments using meticulously prepared sealskin, which is naturally water-resistant. They also employed a unique double-stitch technique with sinew thread that swelled when wet, sealing the needle holes. Lightweight, transparent gut skin was also used for highly waterproof outer layers.

What is an Eskimo parka called? The general term ‘parka’ is widely used. However, specific types include the qulittaq (a general parka) and the amauti, a women’s parka with an enlarged hood or pouch designed to carry a baby close to the body for warmth and transport.

How do Inuit stay warm in the Arctic? Inuit stay warm by wearing expertly crafted layered clothing made from insulating animal furs (like caribou with hollow hairs), utilizing the air trapped between layers for thermal regulation. Their designs also prioritize covering all extremities and minimizing heat loss through openings.

What tools did Inuit use to make clothes? Inuit used a range of traditional tools including the versatile ulu (crescent-shaped knife) for cutting and preparing hides, bone or ivory needles for sewing, and various bone or stone scrapers for cleaning and softening skins.

In conclusion, the craftsmanship inherent in traditional Eskimo clothing is a marvel of human adaptation and ingenuity. From the careful selection of materials like caribou and sealskin to the sophisticated techniques of waterproof stitching and layering, every aspect was meticulously designed for survival in the harshest environment on Earth.

This intricate art form not only ensured physical protection but also served as a profound expression of cultural identity and artistic skill. The enduring legacy of these Arctic garments continues to inspire modern design and reminds us of the deep wisdom held within Indigenous traditions.

Understanding this craftsmanship offers valuable insights into sustainable living, resourcefulness, and the timeless connection between people and their environment. It is a powerful narrative of resilience, innovation, and the mastery of the Arctic.