Death is a universal experience, yet the ways in which humanity confronts and commemorates it are as diverse as the cultures themselves. For Indigenous peoples of the Arctic, a region defined by its extreme climate and profound connection to nature, death and burial practices are deeply intertwined with their spiritual worldview, ancestral beliefs, and the very land that sustains them.

When discussing these traditions, it is important to address terminology. The term ‘Eskimo,’ while historically used, is often considered outdated and, in some contexts, offensive. We will primarily use the preferred and more accurate terms ‘Inuit’ (referring to Indigenous peoples of Canada, Greenland, and parts of Alaska) and ‘Yup’ik’ (primarily of Alaska and Siberia), or the broader ‘Indigenous Arctic peoples,’ to respectfully explore their rich cultural heritage.

The Arctic environment, characterized by vast expanses of ice, snow, and permafrost, has profoundly shaped the daily lives and spiritual beliefs of its inhabitants. This harsh yet beautiful landscape fostered a deep respect for nature and a pragmatic approach to life and death, where survival often depended on understanding and adapting to the land’s rhythms.

Central to many Indigenous Arctic spiritualities is the concept of animism, the belief that all objects, places, and creatures possess a distinct spiritual essence. This worldview means that humans are not separate from nature but are an integral part of an interconnected web of life and spirit. Death is not an end but a transition, a journey for the soul.

The spirit world, often referred to as Sila or Sila-Inua (the spirit of the air or universe), is a pervasive force that influences all aspects of existence. Shamans, known as Angakkuq, played a crucial role in mediating between the human and spirit worlds, guiding souls, healing the sick, and interpreting signs from the unseen realms.

For Indigenous Arctic peoples, the human body was believed to house multiple souls or life forces. For instance, among some Inuit groups, the tarniq (life-giving soul, breath) and inua (personal spirit or essence) were distinct. The proper handling of the deceased was vital to ensure these souls transitioned peacefully and did not linger to cause harm or distress to the living.

Upon a person’s death, traditional practices often began immediately, focusing on respectful treatment of the body and safeguarding the community. There was a period of intense mourning, often accompanied by strict taboos and rituals designed to protect the living from the deceased’s spirit, which might be disoriented or unsettled.

The preparation of the body was a solemn affair, typically undertaken by close family members or designated individuals. The body would be cleaned, dressed in new or special clothing, and sometimes bound or positioned in a fetal or sitting posture, symbolizing a return to the earth or readiness for a new journey.

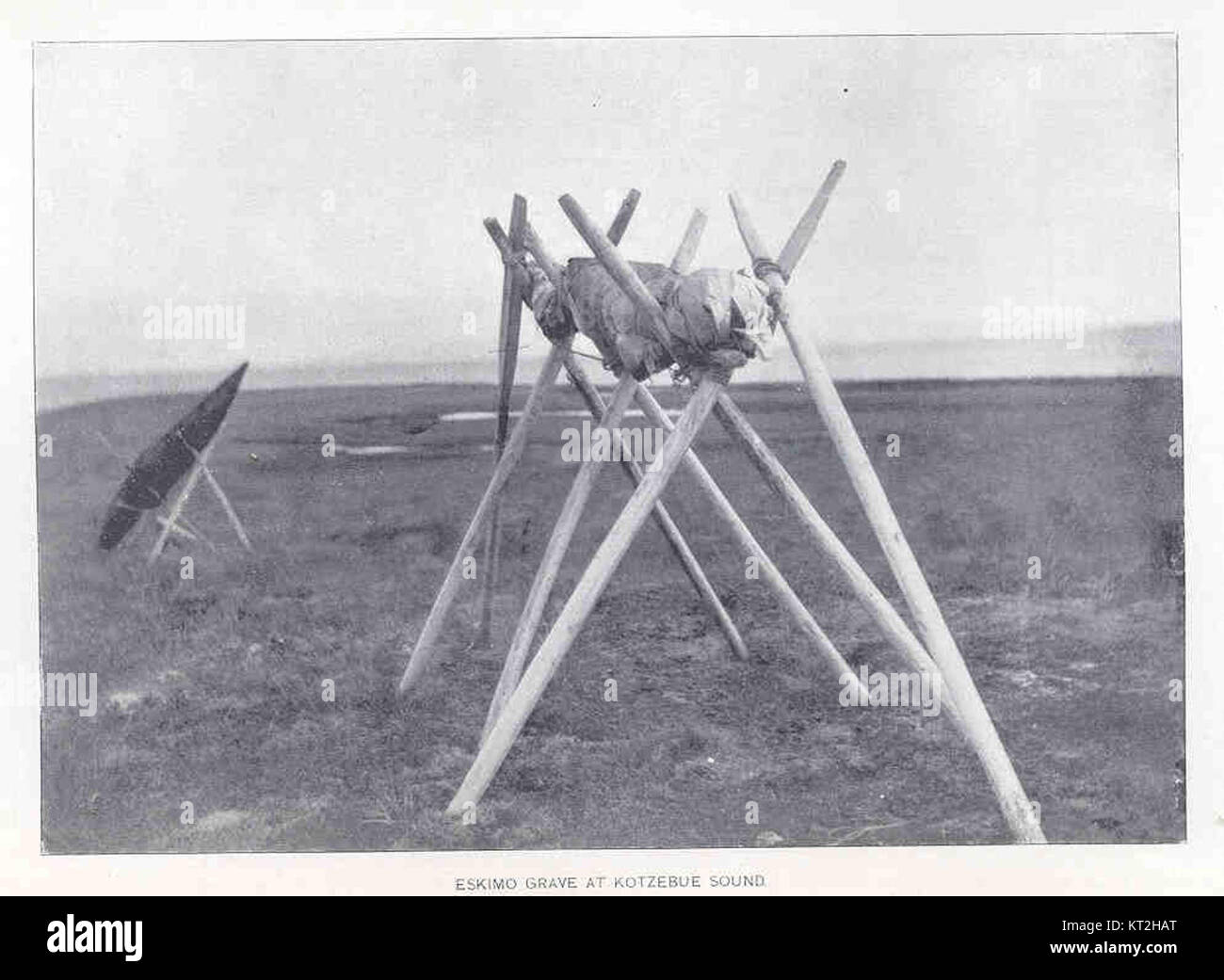

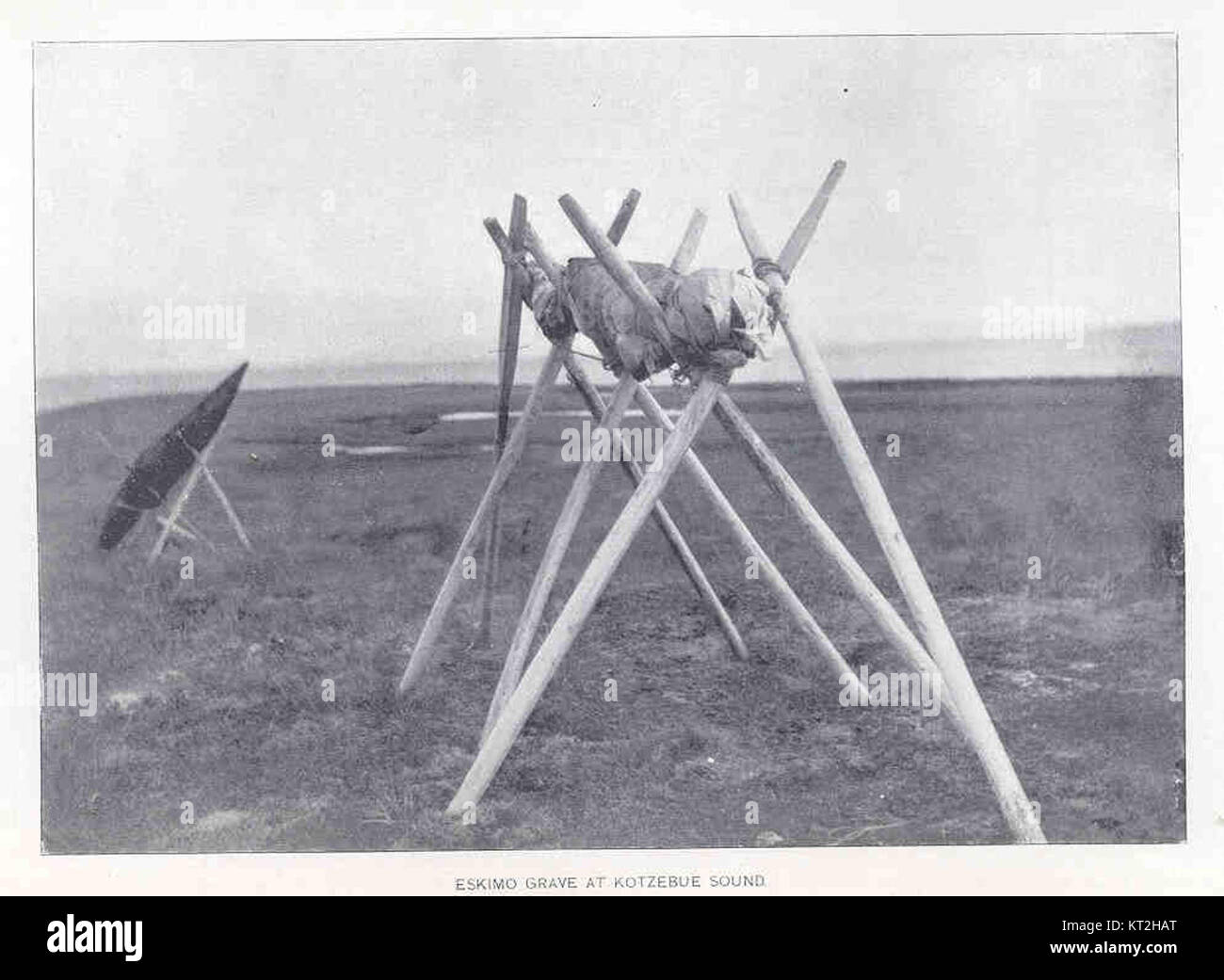

Given the challenges of the permafrost, traditional burial methods varied significantly from those in temperate climates. Digging a deep grave was often impossible. Instead, bodies were frequently placed on the surface of the tundra, sometimes enclosed within stone cairns, wooden structures, or covered with rocks and moss.

These above-ground burials, while seemingly exposed, were a practical adaptation to the environment. The natural elements, including wind and snow, would gradually return the body to the earth. In some coastal communities, sea burials were also practiced, particularly for those lost at sea or under specific ritualistic circumstances, though this was less common than terrestrial methods.

Grave goods were an important part of the burial process, intended to assist the deceased in their journey to the afterlife. These items often included tools, hunting implements, personal ornaments, and sometimes food. The selection of grave goods reflected the individual’s life and status, as well as the community’s beliefs about what was needed for the spirit world.

The orientation of the body was also significant. In many traditions, the deceased might be positioned facing east towards the rising sun, symbolizing new beginnings, or towards a specific land of the dead. These details were not arbitrary but held deep spiritual meaning for the community.

Mourning periods were observed with great solemnity. Family members, especially widows, might adhere to specific restrictions, such as avoiding certain activities, foods, or even speaking for a set duration. These practices were believed to help the bereaved cope with grief and ensure the spirit of the deceased transitioned without impediment.

Community support was paramount during times of loss. Feasts and gatherings were common, serving both to honor the deceased and to reinforce social bonds among the living. Storytelling, drumming, and singing might accompany these events, sharing memories and celebrating the life that had passed.

A unique aspect of some Indigenous Arctic cultures, particularly among the Inuit, is the practice of naming children after deceased relatives. It was believed that by doing so, the spirit or certain qualities of the deceased would live on within the child, ensuring a form of reincarnation or continuous presence within the community.

Beliefs about the afterlife varied, but a common thread was the idea of a spirit world or a land of the dead. This realm was not necessarily a place of reward or punishment in the Western sense, but a continuation of existence, perhaps in a different form or dimension. The journey to this afterlife was often seen as arduous, requiring proper rituals and guidance.

Ensuring the peaceful transition of the soul was critical not only for the deceased but also for the living. Improper burial or neglected rituals could lead to the restless spirit of the deceased lingering, potentially causing misfortune or illness for the community. This fear reinforced the importance of adhering to traditional practices.

While sharing core philosophies, specific death and burial practices exhibit variations across different Indigenous Arctic groups. For instance, the Inuit of Canada, Greenland, and Alaska have distinct regional customs, just as the Yup’ik of Alaska and Siberia maintain their unique traditions, reflecting centuries of adaptation to diverse local conditions.

The arrival of European explorers, traders, and missionaries brought significant changes. Christianization, beginning in the 18th and 19th centuries, gradually introduced Western concepts of heaven, hell, and sin, often conflicting with traditional spiritual beliefs and funerary rites.

Today, many Indigenous Arctic communities blend traditional and modern practices. While Christian burial services are common, elements of ancestral respect, such as naming traditions or community feasts, often persist. This reflects a resilience in maintaining cultural identity amidst external influences.

Modern challenges include the impact of climate change on permafrost, which can disturb ancient burial sites and make traditional land-based burials more complex. There’s also an ongoing effort to revitalize and document traditional knowledge, ensuring that these invaluable cultural practices are preserved for future generations.

What is the Inuit belief about the afterlife? Generally, Inuit beliefs involve a spirit world where souls journey after death. This realm is not necessarily a place of judgment but a continuation of existence. The journey can be challenging, and proper rituals are essential for the soul’s peaceful transition. Some beliefs also involve a form of reincarnation, especially through naming practices.

How did ancient Eskimos bury their dead? Ancient Indigenous Arctic peoples (referring to Inuit, Yup’ik, etc.) often practiced above-ground burials due to permafrost. Bodies were placed in stone cairns, covered with rocks and earth, or sometimes placed in wooden structures. Grave goods, such as tools and personal items, were commonly included to aid the deceased in their journey.

Do Inuit believe in reincarnation? While not reincarnation in the strictly Eastern sense, many Inuit traditions hold a belief that aspects of a deceased person, particularly their name or certain characteristics, can live on or be reborn in a newborn child. Naming a child after a deceased relative is a significant practice tied to this belief.

What are some significant Inuit death rituals? Key rituals include: immediate preparation of the body by family, often involving specific postures; the inclusion of grave goods for the afterlife journey; periods of mourning with specific taboos for the bereaved; community feasts to honor the deceased; and the practice of naming newborns after ancestors.

The profound respect for life and death, the intricate spiritual beliefs, and the remarkable adaptability of Indigenous Arctic peoples are vividly reflected in their death and burial practices. These customs are not merely historical relics but living traditions that continue to evolve, embodying a deep connection to the land, community, and the enduring human spirit.

From the practical necessity of above-ground burials in a permafrost environment to the spiritual significance of grave goods and naming ceremonies, each aspect tells a story of survival, reverence, and cultural richness. Understanding these practices offers invaluable insight into the unique worldview of Arctic communities.

It underscores the importance of cultural sensitivity and the recognition that diverse approaches to death reflect deeply held values and beliefs. The resilience of these traditions, even in the face of external pressures, speaks volumes about the strength of Indigenous identity and heritage.

The journey of the soul, guided by ancient rituals and beliefs, remains a central theme, highlighting a continuous cycle of life, death, and spiritual renewal that transcends the physical realm. These practices remind us that even in the harshest environments, human culture flourishes with profound meaning and ritual.

As we continue to learn and appreciate the rich tapestry of human experience, the death and burial practices of Indigenous Arctic peoples stand as a testament to humanity’s capacity for adaptation, spiritual depth, and an unwavering connection to both the visible and unseen worlds.

The wisdom embedded in these traditions offers a powerful counter-narrative to more generalized views of mortality, inviting us to consider death not just as an ending, but as a complex transition deeply woven into the fabric of community and cosmos. Their stories are a vital part of our global human heritage, deserving of respect and understanding.

The emphasis on community involvement, from preparing the deceased to supporting the bereaved, showcases a communal approach to grief and remembrance, where the loss of one is felt and processed by all. This collective strength is a hallmark of Arctic life.

Moreover, the practical solutions developed for burial in extreme conditions, such as the construction of cairns, demonstrate ingenuity born of necessity and a deep understanding of the environment. These methods were not just pragmatic but imbued with spiritual significance.

The enduring presence of traditional beliefs, even alongside modern influences, illustrates a powerful cultural continuity. Indigenous Arctic peoples have navigated centuries of change, consistently finding ways to honor their ancestors and maintain their distinct identities.

This blend of old and new is not a sign of weakness but of strength, allowing cultures to adapt without losing their essence. It’s a dynamic process that ensures the wisdom of the past continues to inform the present and shape the future.

Ultimately, exploring these practices is an act of cultural appreciation, fostering a deeper understanding of the diverse ways in which humanity grapples with the mysteries of life and death, guided by unique spiritual landscapes and environmental realities. It enriches our collective human story.

The respectful study of these traditions helps to dispel misconceptions and promotes a more nuanced understanding of Indigenous cultures, moving beyond simplistic narratives to appreciate the intricate beauty of their spiritual and social structures.

It reinforces the idea that every culture holds unique insights into the human condition, and that these insights are invaluable for a holistic understanding of our shared world. The Arctic, often seen as remote, offers profound lessons on life’s most fundamental transitions.

In conclusion, the death and burial practices of Indigenous Arctic peoples are a fascinating and deeply meaningful aspect of their cultural identity. Shaped by a challenging environment and a rich spiritual worldview, these traditions—from practical adaptations to profound beliefs about the afterlife—offer a powerful testament to human resilience and cultural depth.

By understanding and respecting these practices, we gain a deeper appreciation for the diverse ways humanity navigates life’s ultimate transition, ensuring that the wisdom and heritage of the Inuit, Yup’ik, and other Arctic peoples continue to be honored and celebrated.