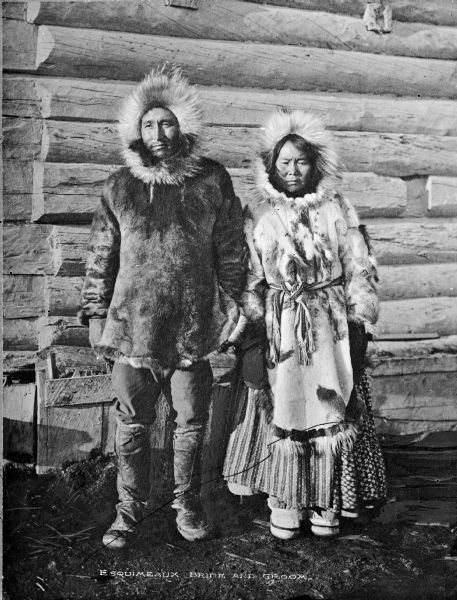

When one thinks of a ‘marriage ceremony,’ images of white dresses, vows, and elaborate celebrations often come to mind. However, for many Indigenous cultures, particularly those in the Arctic, the concept of marriage, and how it was recognized, differed significantly from Western norms. This article will delve into the rich and practical traditions surrounding unions among the Inuit and Yup’ik peoples, often collectively referred to as ‘Eskimo,’ highlighting their unique approaches to partnership and family.

It’s important to begin by acknowledging the term ‘Eskimo.’ While historically used by non-Indigenous peoples, many prefer ‘Inuit’ (referring to people inhabiting Arctic regions of Canada, Greenland, and parts of Alaska) or ‘Yup’ik’ (primarily in Alaska and Siberia) as more accurate and respectful self-identifiers. For the purpose of discussing historical traditions broadly encompassing these groups, we will use ‘Eskimo traditions’ as a collective term while emphasizing the distinct identities within.

Traditional Arctic societies were shaped by the harsh realities of their environment. Survival depended on cooperation, resilience, and practical skills. Marriage, therefore, was often viewed less as a romantic ideal and more as a fundamental social and economic partnership crucial for the well-being of individuals, families, and the wider community.

Unlike many cultures where a specific, formal ‘wedding ceremony’ marked the transition into marriage, traditional Inuit and Yup’ik unions were often recognized through mutual agreement and communal acceptance rather than elaborate rituals. There was rarely a singular event akin to a Western wedding.

Instead, a couple’s union was often solidified through a series of practical arrangements and a gradual integration into each other’s families. This could involve moving in together, the man providing for the woman’s family, or the woman contributing her skills to the man’s household. The community’s acknowledgment of their partnership was the primary form of validation.

Arranged marriages were common, particularly in pre-colonial times. These arrangements were typically made by parents or elders, often when children were very young, sometimes even in infancy. The primary goal was to strengthen family ties, ensure economic stability, and secure the future of the lineage.

The criteria for a suitable match were practical: a young man’s hunting prowess, a young woman’s skills in preparing hides, cooking, and child-rearing were highly valued. These practical considerations outweighed romantic love, though affection and respect often grew within the partnership.

The concept of ‘trial marriage’ or temporary unions also existed in some communities. These informal partnerships allowed individuals to assess compatibility and practical skills before a more permanent arrangement was recognized. If the union proved unsuitable, it could be dissolved without significant social stigma.

One practice that has often been misunderstood by outsiders is ‘wife-sharing’ or ‘spouse exchange.’ It’s crucial to understand this within its specific cultural context. This was not about casual promiscuity but a complex social mechanism often tied to hospitality, kinship, and survival.

In times of travel, hunting expeditions, or during long, isolated winters, sharing spouses could foster deep bonds between families, provide comfort, ensure mutual support, and even strengthen alliances. It was a reciprocal agreement, understood and sanctioned by the community, and often carried specific rules and expectations.

The roles within a traditional Inuit or Yup’ik marriage were distinct yet complementary. Men were primarily responsible for hunting, fishing, and providing raw materials. Their skills in tracking, boat building, and tool making were essential for survival.

Women’s roles were equally vital. They were experts in processing game, preparing food, sewing intricate clothing from hides (crucial for warmth and survival), raising children, and maintaining the home. The success of a household depended entirely on the efficient collaboration of both partners.

Children were highly valued within these societies. Large families were often seen as a blessing, contributing to the family’s labor force and ensuring the continuation of the lineage. Adoption was also a common and respected practice, allowing families to share wealth, support, and perpetuate their names.

The community played a significant role in recognizing and supporting unions. Elders often mediated disputes, offered guidance, and helped maintain social harmony. The strength of the family unit was seen as integral to the strength of the entire community.

Divorce, while not always simple, was generally more pragmatic than in many Western societies. If a union proved dysfunctional, abusive, or simply unproductive, it could be dissolved. The focus was often on ensuring the well-being of the children and the community’s stability.

The arrival of European missionaries, traders, and later, government influences, brought significant changes to these traditional practices. Western concepts of marriage, often involving Christian ceremonies, monogamy, and formal legal recognition, began to be introduced.

Missionaries, in particular, often condemned practices like spouse exchange and polygamy, pushing for unions that conformed to their religious doctrines. This led to a gradual shift away from indigenous customs towards more Westernized forms of marriage.

Today, marriage among Inuit and Yup’ik peoples is a blend of tradition and modernity. Many couples choose to have civil or religious ceremonies, reflecting contemporary societal norms, while still holding deep respect for their cultural heritage.

However, the underlying values of partnership, mutual support, family strength, and community connection remain profoundly important. These fundamental principles continue to shape relationships, even within modern contexts.

The wisdom embedded in traditional Inuit and Yup’ik marriage practices offers valuable lessons. It underscores the importance of practical compatibility, shared responsibility, and the profound role of family and community in supporting enduring partnerships.

Understanding these traditions helps to dispel misconceptions and fosters a deeper appreciation for the diversity of human relationships and cultural expressions around the world. It reminds us that ‘marriage’ is a concept with many forms, each perfectly suited to its unique environment and societal needs.

In summary, traditional ‘Eskimo traditions marriage ceremony’ as a formal event was largely absent. Instead, marriage was a recognized social and economic partnership, often arranged, solidified by mutual agreement and community acknowledgment, and characterized by complementary gender roles essential for survival.

The evolution of these practices reflects the resilience and adaptability of Indigenous peoples in the Arctic, who have navigated profound cultural shifts while striving to maintain the core values that define their identity and relationships.

Key takeaways include:

- Traditional unions were practical agreements, not ceremonial events.

- Arranged marriages were common for family and economic stability.

- ‘Wife-sharing’ was a complex social custom for survival and bonding, not casual.

- Gender roles were distinct and complementary, vital for household success.

- Community recognition was paramount for validating a union.

- Modern marriages blend traditional values with contemporary practices.

This exploration into the nuanced world of Inuit and Yup’ik marriage practices serves as a testament to the ingenuity and interconnectedness of cultures facing the most challenging environments on Earth.

By appreciating these historical and evolving practices, we gain a richer understanding of human relationships and the diverse ways societies have structured family and partnership throughout history.

The emphasis on practical skills, resilience, and community support in these traditional unions provides a powerful counter-narrative to purely romanticized views of marriage.

It highlights that a strong partnership in the Arctic was a matter of survival, where each individual’s contribution was indispensable to the collective well-being.

The concept of ‘family’ extended beyond the nuclear unit, with kinship ties and communal bonds playing a crucial role in providing a safety net and support system for new couples.

Even today, while formal ceremonies may be adopted, the spirit of mutual respect, shared burden, and collective thriving continues to resonate within Inuit and Yup’ik communities.

These traditions underscore that the true ‘ceremony’ of marriage often lies not in a single event, but in the ongoing daily acts of partnership, commitment, and shared life.

Understanding these rich cultural nuances helps us to move beyond superficial understandings and truly appreciate the depth and wisdom embedded in Indigenous ways of life.

The adaptability of these marriage practices over centuries demonstrates the enduring strength of these cultures in the face of immense environmental and social changes.

Ultimately, the story of traditional Inuit and Yup’ik marriage is a story of survival, community, and profound connection, shaped by the unique challenges and beauty of the Arctic.

It teaches us that the essence of a lasting union is often found in shared purpose and unwavering support, regardless of the presence of a formal ceremony.

This deep dive into Arctic marriage traditions serves as a valuable resource for anyone interested in anthropology, Indigenous studies, or the diverse tapestry of human relationships.

We hope this comprehensive overview has shed light on the intricacies and significance of these often-misunderstood cultural practices.

The legacy of these traditions continues to inform and enrich the lives of Inuit and Yup’ik peoples today, representing a powerful connection to their ancestors and their unique heritage.

Embracing this knowledge allows for a more respectful and informed dialogue about Indigenous cultures worldwide.