Reclaiming Narratives: The Enduring Struggle for Eskimo Identity and Self-Determination

The term "Eskimo" evokes images of a people intrinsically linked to vast, icy landscapes, a testament to human resilience in extreme environments. Yet, this widely used exonym, originating from an Algonquian word meaning "eater of raw meat," carries a fraught history and is increasingly rejected by the very communities it purports to describe. Across the circumpolar north – from Alaska to Canada, Greenland to Siberia – the Indigenous peoples collectively referred to as "Eskimo" are diverse, vibrant nations, each with their own names, languages, and cultures, primarily identifying as Inuit, Yup’ik, Inupiat, or Kalaallit. Their story is not merely one of survival, but an ongoing, profound struggle for self-determination, a quest to reclaim their narratives, assert their rights, and forge futures rooted in their distinct identities.

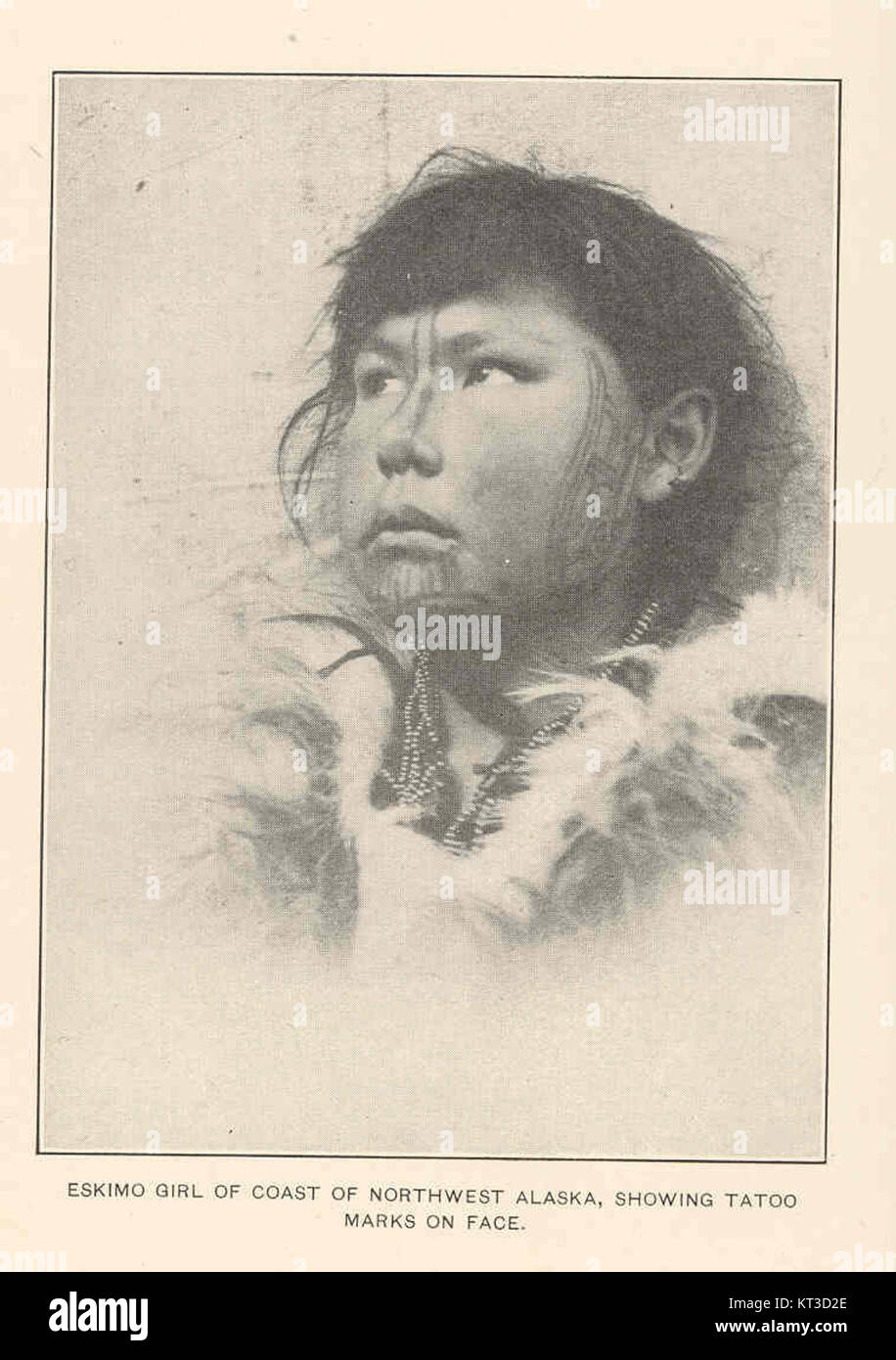

The issue of identity for these Arctic peoples is multifaceted, shaped by millennia of adaptation, distinct cultural practices, and, more recently, the indelible impact of colonialism. Before European contact, these were self-sufficient, complex societies with intricate social structures, spiritual beliefs, and sophisticated technologies perfectly suited to their environment. Their languages, such as Inuktitut, Yup’ik, and Kalaallisut, are not mere communication tools but repositories of vast traditional knowledge, intricate relationships with the land and sea, and unique ways of understanding the world. The wisdom embedded in these languages, often concerning navigation, hunting, animal behavior, and environmental changes, is a critical component of their identity, passed down through generations.

However, the arrival of European explorers, traders, missionaries, and later, government administrators, irrevocably altered their trajectory. What followed was a systematic erosion of self-governance, forced assimilation policies, and the imposition of foreign values. Children were forcibly removed from their families and sent to residential schools, where they were forbidden to speak their languages, practice their cultures, and were often subjected to severe abuse. This traumatic period, which for some extended into the late 20th century, created intergenerational trauma, disrupting cultural transmission and severing vital links to identity. As Sheila Watt-Cloutier, a prominent Inuit leader and Nobel Peace Prize nominee, eloquently states, "The Arctic is not a wilderness, it is our home. Our culture, our identity, our very existence is inextricably linked to the ice and snow." The assault on their homelands and way of life was, therefore, an assault on their very being.

The contemporary quest for self-determination is a direct response to this colonial legacy. It is a demand for the right to govern themselves, manage their resources, preserve their cultures, and shape their own destinies in the modern world. This pursuit takes various forms across the circumpolar region, reflecting the unique political and historical contexts of each nation.

One of the most celebrated examples of Indigenous self-determination is the creation of Nunavut, Canada’s largest and newest territory, established in 1999. This landmark achievement arose from the largest Indigenous land claim settlement in Canadian history, granting the Inuit of the eastern Canadian Arctic significant land ownership and a public government where Inuit form the majority. Nunavut, meaning "our land" in Inuktitut, represents a powerful assertion of identity and political autonomy. It is a jurisdiction where Inuktitut is an official language, traditional knowledge (Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit) is integrated into governance, and Inuit values are intended to guide public policy. While challenges persist in building capacity and addressing socio-economic disparities, Nunavut stands as a beacon of what Indigenous self-governance can achieve.

Similarly, Greenland, home to the Kalaallit (Greenlandic Inuit), has progressively moved towards greater autonomy from Denmark. Gaining Home Rule in 1979 and Self-Government in 2009, Greenland now controls most domestic affairs, including education, healthcare, and resource management, with aspirations for full independence in the future. Their distinct identity is affirmed through their language, Kalaallisut, and their cultural institutions, which are central to national life.

In Alaska, the path to self-determination has been more complex. The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) of 1971 extinguished aboriginal land claims in exchange for 44 million acres of land and nearly $1 billion, distributed among regional and village corporations. While providing a significant economic base and land ownership, ANCSA created a corporate model rather than tribal governments, leading to ongoing debates about the balance between economic development and traditional governance structures. Despite this, Alaska Native peoples continue to assert their sovereignty through tribal councils, cultural revitalization programs, and advocacy for greater governmental recognition and inherent rights. The Inupiat and Yup’ik of Alaska, like their relatives in Canada and Greenland, are deeply invested in maintaining their languages and subsistence hunting practices, which remain vital for both physical and cultural sustenance.

The fight for self-determination is not solely political; it is deeply cultural and environmental. The Arctic is warming at twice the global average, a devastating reality that directly threatens the traditional way of life and the very fabric of identity for these communities. Melting sea ice disrupts ancient hunting routes, threatens the survival of marine mammals, and makes travel increasingly perilous. Permafrost thaw damages infrastructure and alters landscapes, while changes in weather patterns impact food security and cultural practices. As Inuit knowledge holder Aaju Peter often emphasizes, "We are climate change on the ground." For peoples whose identity is so profoundly intertwined with their environment, climate change is not an abstract scientific concept but an existential crisis, demanding their voices be heard in international forums and their traditional knowledge be respected in global climate solutions.

Furthermore, the pursuit of self-determination involves addressing pressing social issues stemming from historical injustices. High rates of suicide, substance abuse, and food insecurity are stark reminders of the ongoing impact of colonialism and the need for culturally appropriate solutions developed and led by Indigenous communities. Education systems that incorporate Indigenous languages and worldviews, healthcare services that are culturally sensitive, and economic development opportunities that align with Indigenous values are crucial components of this self-determined future.

Youth play a critical role in this ongoing journey. While facing the pressures of globalization, urbanization, and the allure of modern technologies, many young Inuit, Yup’ik, and Inupiat are actively engaged in cultural revitalization. They are learning their ancestral languages, participating in traditional arts and practices, and using social media and digital platforms to share their stories, advocate for their rights, and connect with other Indigenous youth globally. This intergenerational transfer of knowledge and resilience is vital for the continued strength of their identities.

Organizations like the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC), representing Inuit from Alaska, Canada, Greenland, and Chukotka (Russia), serve as powerful international voices, advocating for the rights of Inuit on the global stage. The ICC actively champions the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), which affirms Indigenous peoples’ right to self-determination, including their right to freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social, and cultural development. This international framework provides a critical tool for advancing their cause.

In conclusion, the story of the Indigenous peoples often referred to as "Eskimo" is far more complex and dynamic than popular stereotypes suggest. It is a saga of profound cultural resilience, an unwavering commitment to identity, and an ongoing, determined struggle for self-determination. From the groundbreaking political autonomy of Nunavut and Greenland to the nuanced corporate structures in Alaska, these nations are actively shaping their futures, often against immense historical and contemporary challenges. Their journey is a testament to the enduring power of Indigenous identity, the fundamental human right to self-governance, and the urgent necessity of listening to the voices of those who know the Arctic best, as they navigate a rapidly changing world while holding fast to the wisdom of their ancestors. Their fight is not just for themselves, but a beacon for Indigenous peoples worldwide, demonstrating that despite centuries of oppression, their spirit remains unbroken, and their quest for a self-determined future continues to unfold with strength and unwavering resolve.