The Lingering Echoes: How Boarding Schools Wrecked and Reshaped Navajo Culture

For generations, the vast, arid landscapes of Dinétah, the Navajo homeland, cradled a vibrant civilization rooted in centuries of tradition, language, and spiritual connection to the land. This intricate cultural tapestry, however, was violently unraveled by a brutal chapter in American history: the Indian boarding school system. Designed with the explicit goal of "killing the Indian to save the man," these institutions, operating from the late 19th century through the mid-20th century, inflicted profound and lasting damage on Navajo culture, leaving a legacy of trauma that continues to echo today, even as the Diné people relentlessly pursue healing and revitalization.

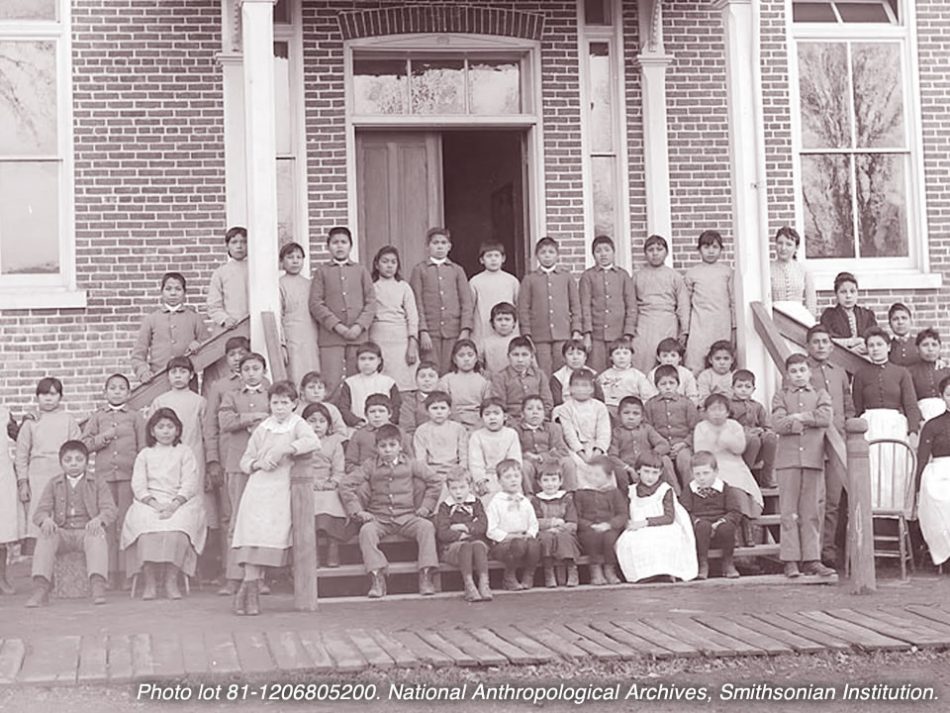

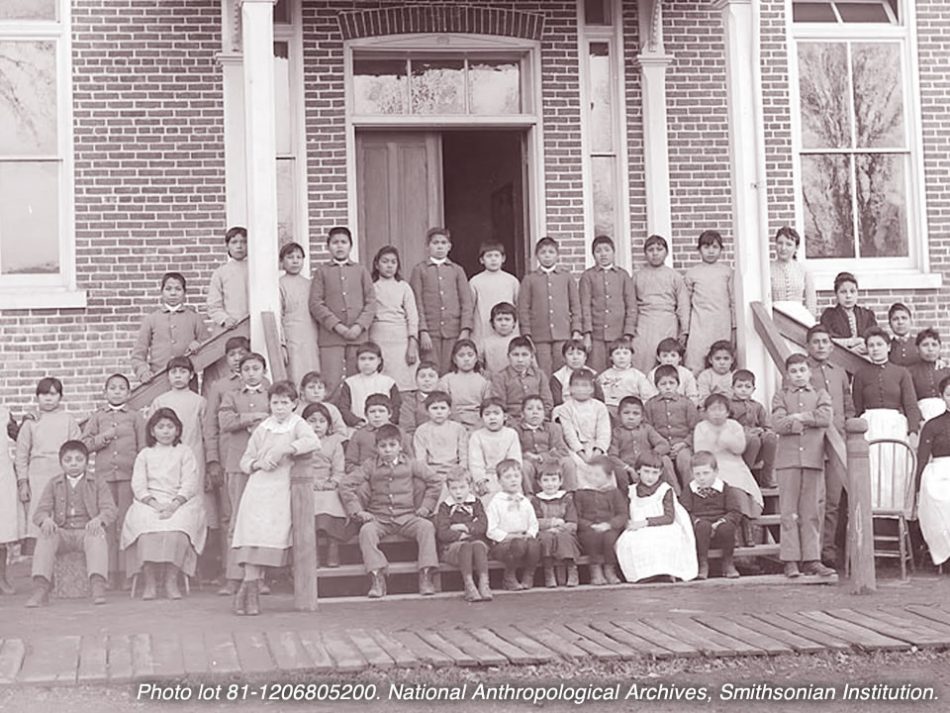

The intent behind these schools was unambiguous cultural genocide. Driven by a federal policy to assimilate Native Americans into white society, children were forcibly removed from their homes, often against the desperate pleas of their parents. Schools like Fort Wingate in New Mexico, Sherman Institute in California, and later, the Intermountain Indian School in Utah, became crucibles where Diné identity was systematically attacked. Richard Henry Pratt, founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, famously articulated the philosophy: "All the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man." This chilling directive was carried out with ruthless efficiency.

Upon arrival, Diné children were stripped of every vestige of their heritage. Their long, sacred hair was shorn, a deeply traumatic act for a culture where hair signifies strength, identity, and connection to ancestors. Traditional clothing was replaced with uniforms, and their ancestral names were discarded in favor of English ones. Most devastatingly, their native language, Diné Bizaad (Navajo language), was strictly forbidden. Children caught speaking their mother tongue faced severe corporal punishment – beatings, public humiliation, or even having their mouths washed out with soap. This deliberate suppression was not just about language; it was about severing the primary conduit of cultural transmission, silencing the stories, songs, prayers, and wisdom passed down through generations.

The curriculum, where it existed beyond forced labor, was a stark departure from traditional Diné learning. Instead of lessons in weaving, silversmithing, sheepherding, or the intricate cosmology of Hózhó (the concept of balance and harmony), children were taught vocational skills deemed appropriate for their "lower station" – farming, domestic service, carpentry. Academic subjects were often rudimentary, designed to prepare them for subservient roles rather than empowering them. This not only denied them access to higher education but also devalued their inherent intelligence and traditional knowledge systems.

Beyond the cultural stripping, the boarding schools were often places of immense suffering. Physical, emotional, and sexual abuse was rampant. Malnutrition, disease (like tuberculosis), and unsanitary conditions were common, leading to high mortality rates. Children were isolated, lonely, and deprived of the familial love and community support that are central to Diné life. The spiritual practices of the Navajo, which emphasize ceremonies like the Kinaaldá (girl’s puberty ceremony) and connections to Diyin Diné (Holy People), were demonized and replaced with Christian teachings, further alienating children from their spiritual roots.

The long-term impact of this systemic trauma on Navajo culture has been profound and multi-generational. One of the most significant consequences is the dramatic decline in Diné Bizaad fluency. While the Navajo Nation remains one of the strongest linguistic groups among Native Americans, the chain of intergenerational transmission was broken for many families. Parents, traumatized by their own experiences, sometimes chose not to teach their children Diné Bizaad, hoping to spare them similar suffering or believing that English was the key to success in the dominant society. This linguistic loss impacts more than just communication; it erodes the ability to fully understand traditional stories, philosophical concepts, and ceremonial practices that are deeply embedded in the language.

Family structures, traditionally strong and extended, were also severely disrupted. Children who grew up without parental nurturing and learned harsh discipline at school often struggled to parent their own children, perpetuating cycles of trauma. The breakdown of traditional parenting models contributed to social issues, including substance abuse, domestic violence, and mental health challenges like PTSD, depression, and anxiety, which are disproportionately high in communities affected by historical trauma. The sense of belonging, vital to Diné identity, was fractured, leaving many individuals feeling caught between two worlds, alienated from their heritage yet not fully accepted by mainstream society.

Economically, the boarding school experience created a workforce ill-equipped for self-sufficiency within their own culture and marginalized within the larger economy. The focus on menial vocational training denied generations the opportunity to develop skills that could foster economic development within the Navajo Nation or compete effectively in professional fields. This contributed to ongoing poverty and economic disparity.

Yet, despite the immense devastation, the Navajo people have shown remarkable resilience. Diné culture, though wounded, has refused to die. In recent decades, there has been a powerful movement toward cultural and linguistic revitalization. The Navajo Nation has taken significant steps to reclaim its educational system, establishing tribal colleges and developing curricula that integrate Diné language, history, and culture. Schools are now actively teaching Diné Bizaad, and immersion programs are working to restore fluency among younger generations. Elders, who often suffered in the boarding schools, are now recognized as invaluable repositories of knowledge, sharing stories, traditional crafts, and ceremonial practices with youth.

The irony of the boarding school era is perhaps best encapsulated by the Navajo Code Talkers of World War II. The very language that was forbidden and punished became an unbreakable code, instrumental in American victory in the Pacific. This remarkable act of patriotism, leveraging the strength of a supposedly "primitive" language, served as a powerful testament to the resilience and unique value of Diné culture, even as the wounds of boarding school policies continued to fester.

Today, healing initiatives within the Navajo Nation address the intergenerational trauma, offering counseling rooted in traditional healing practices and promoting cultural camps that reconnect youth with their heritage. The stories of survivors are being collected and shared, not just as a testament to suffering, but as a source of strength and a call for justice. The Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, launched by the U.S. Department of the Interior, is beginning to unearth the full scope of the system’s horrors, including unmarked graves, offering a path towards truth and reconciliation.

The impact of boarding schools on Navajo culture is a stark reminder of a painful past, a period where a nation attempted to erase an entire civilization. While the scars remain deep, the enduring spirit of the Diné people, their unwavering commitment to their language, land, and traditions, speaks volumes. Their journey is one of immense loss, but also of profound strength, a testament to the power of cultural survival and the ongoing quest for healing and self-determination against overwhelming odds. The echoes of the boarding schools still resonate, but they are increasingly joined by the triumphant sounds of a culture reawakening, reclaiming its voice, and forging a future rooted in the wisdom of its ancestors.