The Long Walk (Hwéeldi) is not merely a historical event for the Diné (Navajo) people; it is a foundational trauma, an enduring scar etched into their collective consciousness, yet paradoxically, a crucible that forged an unyielding resilience. From 1864 to 1868, thousands of Diné were forcibly removed from their ancestral lands (Dinetah) by the U.S. Army, marched hundreds of miles to a desolate internment camp at Bosque Redondo, Fort Sumner, New Mexico. This period of immense suffering, starvation, disease, and cultural suppression irrevocably altered the trajectory of the Diné nation, shaping their identity, language, social structures, and spiritual connection to the land in ways that resonate profoundly to this day.

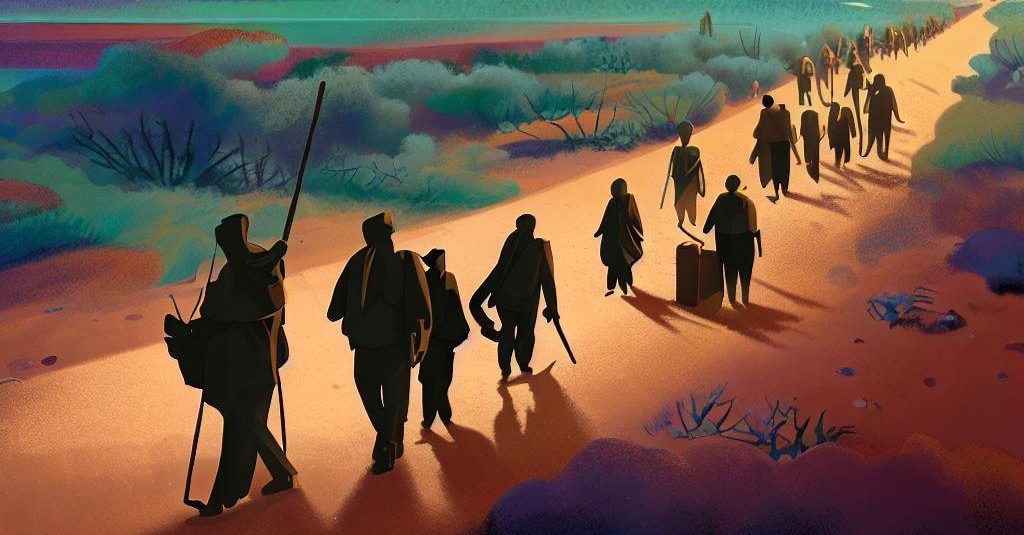

The immediate cultural impact of the Long Walk was catastrophic. The U.S. government’s objective, spearheaded by Colonel Kit Carson, was not just military defeat but cultural eradication. Carson’s "scorched earth" policy systematically destroyed Diné homes, crops, and livestock, eliminating their means of subsistence and forcing surrender through starvation. The forced removal itself, a brutal trek of up to 400 miles on foot, claimed thousands of lives, particularly among the elderly and children. "They drove us like sheep," recounted one survivor, a harrowing memory passed down through generations. This initial act of displacement severed the Diné from Dinetah, their sacred homeland, which is intrinsically linked to their spiritual identity, cosmology, and traditional way of life.

The Diné worldview, rooted in Hózhó (balance and harmony), was shattered by this forced relocation. Their connection to the land is not merely geographical; it is spiritual, economic, and social. Each mountain, river, and canyon holds stories, ceremonies, and sustenance. Being ripped from this sacred landscape was an act of profound spiritual violence, akin to severing the soul from the body. At Bosque Redondo, conditions were horrific. Around 8,000-10,000 Diné were confined to a barren tract of land unable to sustain them. They faced chronic hunger, contaminated water, and rampant disease. Attempts at farming failed, and the U.S. government’s inadequate provisions led to widespread suffering.

Beyond the physical torment, Bosque Redondo was a deliberate attempt at cultural assimilation. The Diné were forced to abandon their traditional attire, discouraged from speaking Diné Bizaad (the Navajo language), and pressured to adopt American farming practices and Christianity. Their complex clan system, which defines social relations and responsibilities, was disrupted. The forced proximity with the Apache, another interned tribe with whom the Diné had a long history of conflict, further exacerbated tensions and suffering. This concentrated attempt to dismantle their cultural fabric aimed to erase their identity, transforming a proud, self-sufficient nation into a dependent, compliant populace.

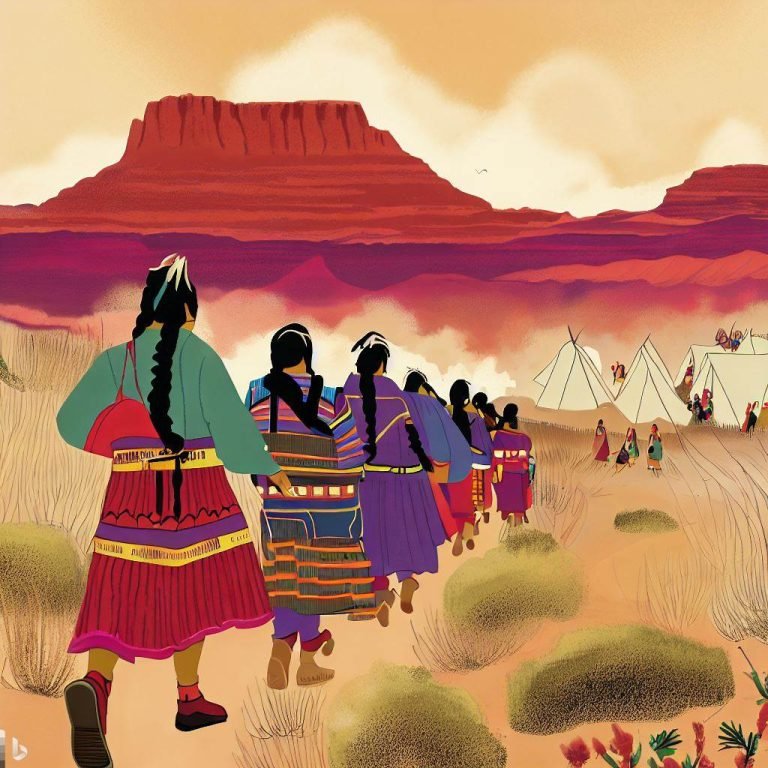

Yet, the story of Hwéeldi is not solely one of victimhood; it is equally a testament to extraordinary human resilience. Against all odds, the Diné survived. In 1868, after four years of immense suffering, Diné leaders, including Barboncito and Manuelito, negotiated the Treaty of 1868 with the U.S. government – a unique achievement in Native American history, as it allowed them to return to a portion of their ancestral lands. The journey home, though still arduous, was a spiritual rebirth. "When we saw the first familiar peaks, a cry went up through the whole column," an elder recalled. "We were home." This return was not just a physical act but a profound cultural reaffirmation, solidifying their indomitable spirit and their unyielding connection to Dinetah.

The cultural impact of the Long Walk extends far beyond the immediate suffering and return. It created a deep, intergenerational trauma that continues to manifest in various forms today. This historical trauma, a concept describing the cumulative emotional and psychological wounding over the lifespan and across generations, has been linked to higher rates of depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and other mental health challenges within the Diné community. The stories of Hwéeldi are not abstract history; they are living narratives passed down, shaping how individuals and families perceive their place in the world and their relationship with external authorities. As Diné scholar Dr. Jennifer Nez Denetdale notes, "The Long Walk is not just an event that happened to us; it is part of who we are, woven into our very being."

Paradoxically, the Long Walk also served to strengthen and reinforce key aspects of Diné culture, albeit through immense hardship.

1. Language (Diné Bizaad): The attempts to suppress Diné Bizaad at Bosque Redondo inadvertently made it a potent symbol of survival and resistance. For many, speaking their language became an act of defiance, a way to maintain their identity in the face of assimilation. Today, Diné Bizaad remains one of the most vibrant and widely spoken indigenous languages in North America, its preservation a direct legacy of the resilience forged during Hwéeldi. It is the vessel through which stories, ceremonies, and knowledge are passed down, ensuring the continuation of Diné thought and worldview.

2. Oral Tradition and Storytelling: The Long Walk became a cornerstone of Diné oral tradition. Stories of suffering, courage, and survival are recounted by elders, passed from generation to generation, ensuring that the lessons and memories of Hwéeldi are never forgotten. These narratives serve as both a warning against oppression and an inspiration for resilience. They are not merely historical accounts but living lessons that reinforce cultural values, kinship bonds, and the importance of perseverance. Songs and ceremonies also incorporate elements related to the Long Walk, helping to process the trauma and celebrate survival.

3. Connection to Land (Dinetah): The forced removal and subsequent return profoundly deepened the Diné’s spiritual and emotional connection to Dinetah. The experience of being separated from their sacred mountains and then fighting to return cemented the land’s central role in their identity. It underscored the understanding that their existence, well-being, and cultural continuity are inseparable from their ancestral territory. This reinforced connection fuels ongoing efforts for land protection, environmental stewardship, and the assertion of tribal sovereignty.

4. Kinship and Community Bonds: The shared trauma of the Long Walk forged an unbreakable bond among the survivors. Mutual support, cooperation, and the strength of the clan system were essential for survival both during the march and at Bosque Redondo, and during the arduous process of rebuilding afterwards. This experience reinforced the importance of community, interdependence, and collective action, values that continue to underpin Diné society.

5. Political Consciousness and Self-Determination: The Long Walk and the subsequent Treaty of 1868 laid the groundwork for modern Diné political consciousness. The ability to negotiate their return demonstrated agency and the importance of collective advocacy. This experience instilled a deep-seated distrust of external government interference, fueling a drive for self-governance and the protection of tribal sovereignty that continues to define the Navajo Nation’s political landscape today. The lessons of Hwéeldi inform their approaches to treaty rights, resource management, and interactions with federal and state governments.

Today, the Long Walk is not relegated to dusty archives; it is a living history. Annual remembrance walks and ceremonies commemorate the suffering and celebrate the resilience. Educational initiatives ensure that younger generations understand this pivotal period. Diné artists, poets, and musicians draw inspiration from Hwéeldi, using their crafts to express the pain, healing, and enduring spirit of their people. Modern Navajo Nation leaders frequently invoke the memory of the Long Walk when discussing challenges and aspirations, emphasizing the importance of sovereignty, self-sufficiency, and cultural preservation.

In conclusion, the cultural impact of the Long Walk on the Navajo people is a complex tapestry woven with threads of profound trauma and extraordinary resilience. It represents a wound that continues to heal across generations, yet it also stands as a testament to the indomitable spirit of the Diné. The experience of Hwéeldi did not break the Navajo; instead, it forged a stronger, more self-aware nation, deeply rooted in its language, land, and traditions. It is a powerful reminder that while attempts at cultural annihilation can inflict immense pain, the human spirit, especially when fortified by a rich cultural heritage, possesses an incredible capacity for survival, adaptation, and the eventual triumph of identity. The Long Walk remains a profound testament to the power of cultural memory and the enduring will of a people to define their own destiny.