Chickasaw Removal Routes: Mapping the Forced Migration to Indian Territory

The story of the Chickasaw Nation is one of profound resilience etched against a backdrop of unimaginable loss. Their forced migration from ancestral lands in the American Southeast to Indian Territory, now Oklahoma, represents a harrowing chapter in American history, often overshadowed by the broader narrative of the "Trail of Tears." Yet, the Chickasaw Removal, marked by distinct routes and unique challenges, is a powerful testament to a people’s struggle for survival and self-determination. Mapping these routes is not merely a cartographic exercise; it is an act of remembering, a visualization of a trauma that reshaped a nation.

For centuries, the Chickasaw people flourished across a vast domain encompassing parts of present-day Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee, and Kentucky. Their society was sophisticated, marked by a strong agricultural tradition, a formidable military reputation, and a complex political structure. They were a sovereign nation, engaging in treaties and trade with European powers and the nascent United States. Their lands, fertile and strategically located, became increasingly coveted by a rapidly expanding American populace, fueled by the insatiable demands of the cotton kingdom and the ideology of Manifest Destiny.

The pressure mounted in the early 19th century, culminating in the Indian Removal Act of 1830, championed by President Andrew Jackson. This act, despite its deceptive premise of "voluntary exchange," was a federal mandate designed to forcibly displace all Native American nations east of the Mississippi River. Unlike some of their neighbors, such as the Cherokee who fought their removal through legal battles, the Chickasaw initially attempted a different strategy: negotiation and a deferred removal. They were economically savvy, often wealthy, and understood the value of their lands. Their goal was to secure the best possible terms for their inevitable displacement, believing resistance would be futile against the overwhelming military might of the United States.

This approach led to a series of treaties, most notably the Treaty of Pontotoc Creek in 1832. Under duress, Chickasaw leaders ceded their ancestral lands, with the understanding that they would receive financial compensation and find new lands in the West. However, the subsequent years were fraught with challenges. The U.S. government was slow to pay, and the promised lands in Indian Territory were not immediately available. This led to a unique situation where the Chickasaw had to purchase land from the Choctaw Nation, who had been removed earlier, through the Treaty of Doaksville in 1837. This financial arrangement, a testament to Chickasaw economic acumen even in crisis, set them apart from other removed tribes, but it did not mitigate the suffering of the journey.

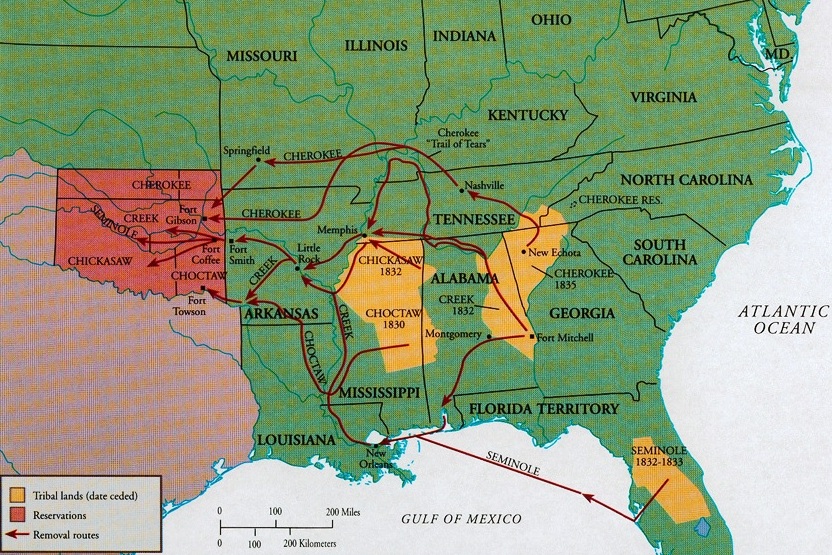

The actual removal of the Chickasaw Nation largely occurred between 1837 and 1838, though smaller groups moved earlier and later. Their migration was not along a single "trail" but rather a network of routes, dictated by geography, logistics, and the availability of resources. These routes can be broadly categorized into land and water passages, each presenting its own set of horrors.

The Land Routes:

Many Chickasaw groups, often accompanied by their enslaved African American laborers, livestock, and what few possessions they could carry, embarked on overland journeys. These routes typically began in their traditional homelands in Mississippi and Alabama. One common trajectory involved moving northwest through Mississippi, often consolidating near staging areas like Pontotoc or Tuscumbia (now in Alabama). From there, they would proceed across the Mississippi River, either ferried across or, in some cases, traveling north to cross near Memphis, Tennessee.

Once across the Mississippi, the journey continued westward through Arkansas. This segment of the route was particularly arduous, traversing dense forests, swamps, and rugged terrain. Roads, if they existed, were often little more than crude tracks, turning into quagmires during rain and dust bowls in dry spells. The scarcity of potable water and provisions was a constant threat. Federal contractors, often corrupt and inefficient, were tasked with supplying the emigrants, but supplies were frequently inadequate, spoiled, or stolen.

These land routes would eventually lead to their new lands in what is now south-central Oklahoma. The journey was slow, averaging perhaps 10-15 miles a day on good days, but often less. The physical toll was immense. People walked, rode horses, or were transported in wagons. For the sick and elderly, every step was agony.

The Water Routes:

For some Chickasaw detachments, particularly those originating closer to major rivers, water transport offered an alternative, though not necessarily less dangerous, path. Groups would often gather along the Tennessee River, travel downstream to the Ohio River, and then into the mighty Mississippi. From there, they would navigate south to the mouth of the Arkansas River and then travel upstream into Indian Territory.

River travel, while seemingly less strenuous, presented its own unique set of perils. Overcrowded steamboats became breeding grounds for disease. Cholera, smallpox, and dysentery swept through the confined quarters, claiming lives with horrifying speed. Accounts from the period describe bodies being thrown overboard, unmarked graves dug hastily along riverbanks. The psychological impact of watching loved ones succumb to illness, far from their sacred burial grounds, was devastating. The journey by water could also be unpredictable, with low water levels stranding boats for weeks, or sudden storms capsizing vessels.

The Human Cost and Overlooked Narratives:

Regardless of the route, the Chickasaw Removal was a humanitarian catastrophe. It’s estimated that roughly 4,000 to 5,000 Chickasaw individuals, along with hundreds of their enslaved people, made the forced journey. The exact number of deaths is difficult to ascertain, but historical accounts suggest a significant percentage perished from disease, starvation, exposure, and exhaustion. One historian noted that "the Chickasaw lost at least a quarter of their population during the removal process," a figure that underscores the genocidal impact of the policy.

The Chickasaw experience also highlights a crucial, often overlooked, aspect of the removals: the forced migration of enslaved African Americans. These individuals, numbering in the hundreds, were considered property and were marched alongside their Chickasaw owners, sharing the same harsh conditions, suffering, and loss, but without the hope of eventual freedom or self-determination that even their enslavers possessed. Their untold stories are an integral part of mapping the removal routes, revealing layers of oppression within an already tragic narrative.

Mapping as Remembrance and Resilience:

Today, mapping these Chickasaw Removal Routes is more than just tracing lines on an old map. It is a powerful tool for historical preservation and cultural revitalization. Each segment of the journey, each river crossing, each temporary encampment represents a point of suffering, but also a point of survival. Descendants of the Chickasaw Nation can trace their ancestors’ paths, connecting with a profound history that shaped their identity.

The Chickasaw Nation, despite the immense trauma of removal, demonstrated extraordinary resilience. Upon arriving in Indian Territory, they immediately began rebuilding. They established new farms, schools, and a sophisticated government based on their traditional structures, adapted to their new environment. Their perseverance laid the foundation for the vibrant, prosperous, and self-governing nation that exists today.

Mapping these routes helps us understand the true geographical and human scale of the Indian Removal Act. It brings to light the specific struggles of the Chickasaw, whose story, while part of a larger tragedy, has its own distinct contours. It forces us to confront the uncomfortable truths of American expansion and the devastating consequences of policies driven by greed and racial prejudice.

The Chickasaw Removal Routes are not just lines on a map; they are arteries of memory, flowing with the tears, sweat, and blood of a people who endured unimaginable hardship. They stand as a permanent reminder of the strength of the human spirit in the face of profound injustice and the enduring legacy of a nation that refused to be erased. By continuing to map, research, and tell these stories, we honor those who walked these paths and ensure that their forced migration, and their indomitable spirit, are never forgotten.