The Unseen Crisis: Rebuilding Homes and Hope in Native American Communities

Deep within the heart of America, often out of sight and out of mind for many, lies a pervasive and deeply rooted humanitarian crisis: the chronic lack of adequate housing in Native American tribal communities. Generations of systemic neglect, land dispossession, and underfunding have created a landscape where overcrowded, dilapidated, and often unsafe dwellings are not the exception, but the norm. This isn’t merely an issue of bricks and mortar; it’s a profound challenge impacting health, education, economic opportunity, and the very fabric of cultural survival. Yet, amidst these stark realities, Native nations are forging innovative, community-based solutions, demonstrating remarkable resilience and self-determination in their quest to rebuild homes and restore hope.

The scale of the crisis is staggering. According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), an estimated 68,000 new housing units are needed on reservations immediately, with many more requiring substantial renovation. Overcrowding rates in tribal areas are 16 times the national average. Homes frequently lack basic amenities like indoor plumbing, running water, or electricity. Dilapidated structures, often exposed to harsh elements, are commonplace, leading to severe health disparities, from respiratory illnesses exacerbated by mold and poor ventilation to mental health struggles stemming from instability and stress. This isn’t just a housing problem; it’s a public health emergency, an educational barrier, and a fundamental impediment to economic development.

Historical Wounds and Systemic Barriers

To understand the current housing crisis, one must look to its deep historical roots. The forced removal of Native peoples from their ancestral lands, the creation of reservations on often marginal lands, and a century of federal policies aimed at assimilation, rather than support, laid the groundwork for today’s challenges. Treaties were broken, resources were plundered, and self-governance was undermined. The General Allotment Act of 1887, for instance, fragmented tribal lands into individual parcels, leading to complex "heirship" issues where a single piece of land can have hundreds of owners, making it nearly impossible to secure clear title for housing development.

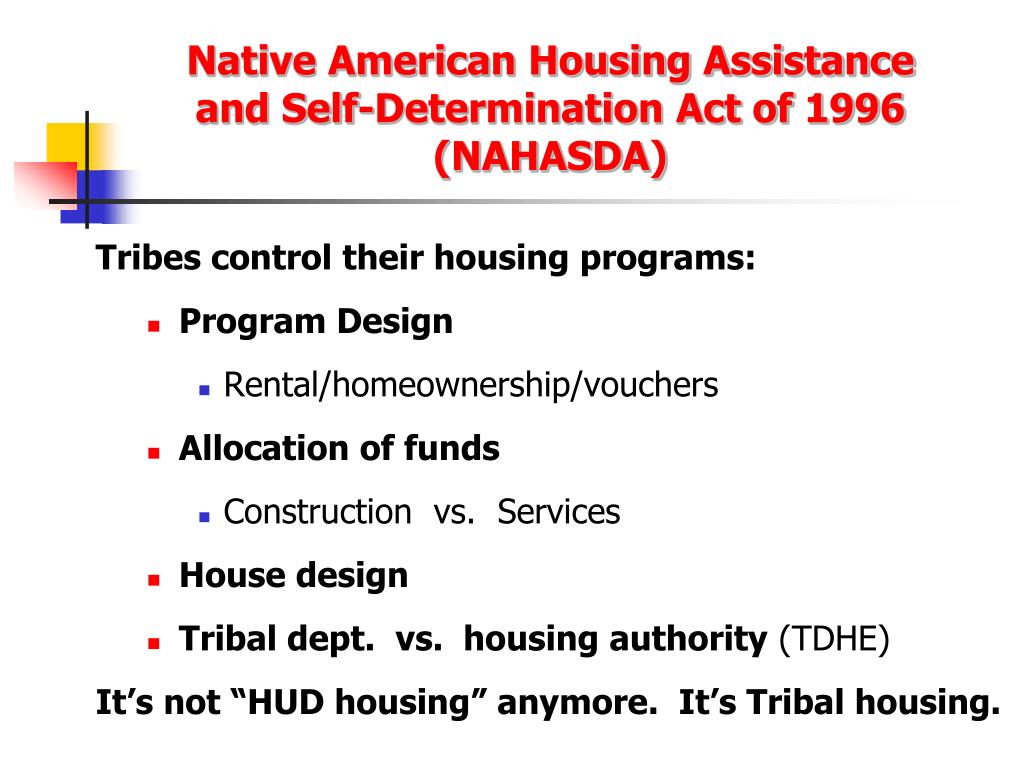

Beyond historical injustices, contemporary systemic barriers persist. Federal funding for Native American housing, primarily through the Native American Housing Assistance and Self-Determination Act (NAHASDA), has been chronically insufficient. While NAHASDA was a landmark piece of legislation empowering tribes to manage their own housing programs, its funding levels have rarely met the immense need. In 2023, NAHASDA received $780 million, a significant sum, but still a fraction of what is required to address the estimated multi-billion dollar housing deficit. "The federal government has a trust responsibility to Native American tribes," states Robert G. Beaulieu, former President of the National American Indian Housing Council. "That responsibility includes ensuring safe, decent, and affordable housing. For too long, that trust has been neglected, leaving our communities to shoulder an impossible burden."

Furthermore, the unique legal status of trust land on reservations complicates conventional homeownership and development. Lenders are often reluctant to issue mortgages without clear title, and the collateral requirements for loans are difficult to meet when land cannot be easily foreclosed upon. Infrastructure—access to roads, water, sewer, and reliable electricity—is often non-existent or inadequate, making new construction prohibitively expensive. High unemployment rates, limited access to capital, and geographical isolation further exacerbate the problem, trapping many families in cycles of poverty and housing instability.

Community-Based Solutions: Resilience and Innovation

Despite these formidable challenges, Native American tribes are not passively waiting for federal intervention. They are actively, and often ingeniously, developing and implementing community-based solutions rooted in self-determination, cultural preservation, and sustainable practices.

Central to many of these efforts are Tribal Housing Authorities (THAs). These tribally-controlled entities are the frontline responders, managing NAHASDA funds, developing housing programs, and often acting as developers, property managers, and social service providers. THAs are crucial because they understand the unique cultural, environmental, and economic contexts of their respective communities, allowing for tailored solutions that federal programs often miss.

One of the most promising avenues is innovative and culturally appropriate construction methods. Many tribes are embracing sustainable building practices that respect the environment and reflect traditional architectural styles. The Santo Domingo Pueblo in New Mexico, for example, has long utilized adobe construction, which is energy-efficient and blends seamlessly with the landscape. Modern interpretations incorporate contemporary building codes while retaining cultural integrity. Other tribes are exploring modular and tiny home construction to address affordability and speed of deployment. These pre-fabricated units can be built off-site and assembled quickly, offering a more immediate solution to overcrowding.

The Northern Cheyenne Nation in Montana, facing harsh winters and a lack of local contractors, has explored training tribal members in sustainable straw bale construction. This not only provides energy-efficient homes but also creates local jobs and fosters a sense of ownership and skill development within the community. Similarly, the Ramah Navajo Housing Authority in New Mexico has spearheaded projects incorporating passive solar design and natural materials, reducing long-term energy costs for residents—a critical factor in communities with limited income.

Leveraging Partnerships and Diverse Funding Streams

While NAHASDA remains a cornerstone, tribes are increasingly savvy at leveraging other federal programs and forging strategic partnerships. They are tapping into USDA Rural Development loans and grants for housing and infrastructure, Treasury Department programs, and even mainstream HUD programs like Community Development Block Grants (CDBG) and HOME Investment Partnerships. Collaboration with non-profit organizations like Habitat for Humanity International, which has dedicated programs for Native American housing, and the Native American Housing Institute, provides additional resources, technical assistance, and volunteer labor.

Crucially, these partnerships are often structured to empower tribal control. Rather than being passive recipients, tribes dictate the terms, ensuring projects align with their visions and needs. This self-determination extends to developing tribal building codes that reflect local conditions and cultural preferences, and training tribal members in construction trades, creating a skilled workforce that can continue to build and maintain homes long-term, fostering local economic growth.

Addressing Land Tenure and Financial Innovation

The complex issue of heirship land is also being tackled with creativity. Some tribes are developing their own tribal land codes to simplify leasing processes and consolidate fractional interests, making it easier to develop housing. Financial innovations are also emerging, with tribes establishing tribal lending institutions and developing down payment assistance programs tailored to their members’ unique circumstances. These efforts aim to bridge the gap left by conventional banking systems that are often ill-equipped to operate on trust land.

For example, the Oglala Sioux Tribe on the Pine Ridge Reservation, facing some of the most severe housing shortages in the nation, has partnered with organizations to develop innovative financing mechanisms and build culturally relevant, affordable homes. Their efforts often involve job training programs for residents, ensuring that the benefits of housing development extend beyond mere shelter to encompass economic empowerment.

Challenges Remain, but Hope Persists

Despite these inspiring efforts, significant challenges persist. The chronic underfunding of federal programs remains a major hurdle, forcing tribes to do more with less. Bureaucratic complexities, often stemming from federal regulations not designed for tribal contexts, can slow down projects. The lack of basic infrastructure on many reservations—roads, water, sewer, and broadband internet—continues to inflate construction costs and limit development potential. Moreover, climate change poses new threats, with extreme weather events disproportionately impacting vulnerable housing and requiring resilient, climate-adaptive building strategies.

However, the story of Native American tribal housing is ultimately one of resilience, ingenuity, and unwavering hope. From the sustainable adobe homes of the Pueblo nations to the modular innovations on the Plains, tribes are demonstrating that community-based approaches, rooted in self-determination and cultural values, are not just viable but essential. They are not merely building houses; they are rebuilding communities, revitalizing cultures, and restoring dignity. The path forward demands sustained federal investment, recognition of tribal sovereignty in housing policy, and a commitment to addressing the historical injustices that created this crisis. Only then can all Native American families truly have a safe, decent, and culturally appropriate place to call home, fulfilling a long-neglected trust responsibility and ensuring a brighter future for generations to come.