Native American Tribal Treaties: Historical Agreements and Ongoing Legal Obligations

The relationship between the United States government and Native American tribes is a complex tapestry woven with threads of diplomacy, conflict, and a long history of legal agreements. At the heart of this intricate relationship lie treaties – solemn, binding documents signed between sovereign nations. Far from being mere historical artifacts, these treaties remain living instruments, shaping the legal landscape, defining tribal sovereignty, and underpinning the ongoing responsibilities of the federal government. Understanding their origins, their often-violated provisions, and their modern-day implications is crucial to comprehending the unique status of Native nations within the American legal system.

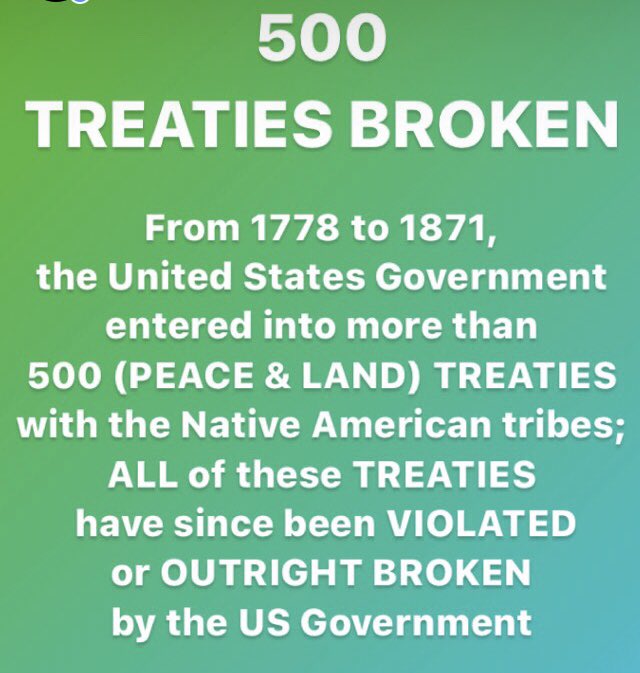

From the nascent days of European colonization, agreements were struck between settlers and Indigenous peoples, initially to secure peace, trade, and passage. However, it was after the American Revolution, as the United States emerged as a sovereign power, that the formal treaty-making era truly began. Recognizing Native American tribes as distinct political entities, the U.S. government entered into over 370 treaties with various tribes between 1778 and 1871. These treaties served multiple purposes: to define boundaries, ensure peace, secure alliances, and, most frequently, to facilitate the cession of vast tracts of tribal land in exchange for annuities, goods, services, and the establishment of reservations.

The legal standing of these agreements was unequivocal. Under the U.S. Constitution, Article II, Section 2, Clause 2, the President has the power to make treaties with the "advice and consent" of the Senate. More critically, Article VI, Clause 2, the Supremacy Clause, declares that "all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land." This means that treaties with Native American tribes hold the same legal weight as treaties with foreign nations like France or Great Britain. They are not merely promises, but foundational legal documents that cannot be unilaterally abrogated by one party without consent or due process.

This principle was famously affirmed in Worcester v. Georgia (1832), a landmark Supreme Court case. Chief Justice John Marshall, writing for the majority, declared that the Cherokee Nation was "a distinct community, occupying its own territory… in which the laws of Georgia can have no force." Marshall articulated the concept of inherent tribal sovereignty, stating that tribes were "distinct, independent political communities, retaining their original natural rights" and that treaties were "contracts made in the course of the exercise of a sovereign power." This decision also laid the groundwork for the federal government’s "trust responsibility" – a unique legal and moral obligation to protect tribal lands, assets, resources, and self-governance, which continues to be a cornerstone of federal Indian law.

Despite this clear legal framework, the history of treaty relations is overwhelmingly one of broken promises and systemic violations by the United States. As the nation expanded westward, driven by "Manifest Destiny" and an insatiable hunger for land and resources, treaties became inconvenient obstacles. The gold rush in California, the desire for fertile agricultural lands, and the discovery of minerals often led to the renegotiation, forced cession, or outright disregard of treaty stipulations. The Indian Removal Act of 1830, which led to the forced relocation of southeastern tribes along the "Trail of Tears," is a stark example of such betrayal, occurring despite existing treaties that guaranteed their land tenure.

One of the most emblematic examples of a violated treaty is the Treaty of Fort Laramie of 1868. Signed after Red Cloud’s War, a successful resistance movement by the Lakota Sioux and their allies, this treaty established the Great Sioux Reservation, encompassing all of present-day South Dakota west of the Missouri River, including the sacred Black Hills. It guaranteed "undisturbed use and occupation" of this territory and hunting rights in other unceded areas. However, within six years, gold was discovered in the Black Hills, triggering an influx of miners and settlers. The U.S. government, despite its treaty obligations, failed to remove the trespassers and instead orchestrated a campaign to force the Sioux to sell the Black Hills. When the Sioux refused, the government initiated the Black Hills War (1876-1877), ultimately seizing the land.

This profound injustice continues to resonate today. In United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians (1980), the Supreme Court ruled that the U.S. had illegally taken the Black Hills and awarded the Sioux over $100 million in compensation, including interest. Yet, the Sioux Nation has consistently refused to accept the money, which now sits in a trust fund worth over $1.5 billion, maintaining their demand for the return of the land itself, not merely payment for its theft. This stands as a powerful testament to the enduring significance of treaty promises and the unwavering commitment of tribes to their ancestral lands.

Another vital category of treaties involves the reserved rights doctrine. Unlike land cessions where tribes "give up" rights, the reserved rights doctrine holds that tribes retain all rights not explicitly ceded in a treaty. This is particularly relevant for hunting, fishing, and gathering rights. For instance, treaties signed in the Pacific Northwest in the mid-19th century, such as the Treaty of Medicine Creek (1854), saw tribes cede vast territories but explicitly "reserved" their right to fish "at all usual and accustomed grounds and stations." These seemingly simple phrases became the basis for landmark legal battles a century later.

The Boldt Decision (1974), officially United States v. Washington, affirmed these reserved fishing rights, ruling that treaty tribes were entitled to 50% of the harvestable salmon and steelhead returning to their traditional fishing grounds. This decision was not merely about fish; it was a profound reaffirmation of treaty promises and tribal sovereignty, recognizing that tribes had reserved, not been granted, these rights. The ongoing management of these resources requires constant collaboration and, at times, contention between state, federal, and tribal governments, illustrating the living nature of these historical agreements.

The era of treaty-making formally ended in 1871, with Congress passing an appropriations rider stating that "no Indian nation or tribe within the territory of the United States shall be acknowledged or recognized as an independent nation, tribe, or power with whom the United States may contract by treaty." This did not, however, invalidate existing treaties or diminish their legal force. Instead, it shifted the relationship from treaty-making to congressional acts, executive orders, and agreements, often unilaterally imposed. The subsequent period saw further attempts to undermine tribal sovereignty and land bases, most notably through the General Allotment Act (Dawes Act) of 1887, which aimed to break up tribal communal lands into individual parcels, often leading to massive land loss for tribes.

Despite these historical assaults, the legal and moral obligations enshrined in treaties persist. Today, the "nation-to-nation" relationship, rooted in these original agreements, continues to define interactions between the federal government and the 574 federally recognized tribes. This relationship mandates the federal government to consult with tribes on a wide range of issues, from resource management and environmental protection to healthcare and education. Federal trust responsibility remains a legal obligation, requiring the government to act in the best interest of tribes, protecting their lands, resources, and inherent rights.

Modern tribal governments exercise significant self-governance, operating their own judicial systems, police forces, schools, healthcare facilities, and economic enterprises, often funded in part by federal resources allocated under the trust responsibility. Contemporary legal battles continue to arise over water rights, land claims, gaming compacts, and the protection of sacred sites – all of which frequently trace their legal lineage back to treaty provisions or the principles established during the treaty era. These ongoing legal disputes underscore that treaties are not static historical documents but dynamic instruments that continue to shape the present and future of Native American communities.

In conclusion, the Native American tribal treaties represent a foundational, yet often fraught, chapter in American history. They are profound legal documents that recognized tribal sovereignty, defined territorial boundaries, and established enduring obligations. While the U.S. government’s record of adherence has been deeply flawed, the treaties themselves remain the supreme law of the land, affirming the inherent rights of Indigenous nations. The ongoing struggle for justice, the assertion of tribal sovereignty, and the insistence on the federal government’s trust responsibility all stem from these historical agreements. A true understanding of American jurisprudence and the enduring presence of Indigenous nations demands a full and honest reckoning with the promises made, and too often broken, in these solemn covenants.