Native American Tribal Justice Systems: Traditional Practices and Modern Courts

Across the diverse tapestry of Native American nations, the pursuit of justice has always been deeply interwoven with cultural identity, community well-being, and sovereign self-determination. From ancient practices rooted in healing and restoration to the sophisticated modern court systems operating today, tribal justice represents a profound and often overlooked dimension of American jurisprudence. These systems are not mere replicas of federal or state models; they are distinct entities, continually evolving to honor ancestral wisdom while navigating the complexities of contemporary legal challenges.

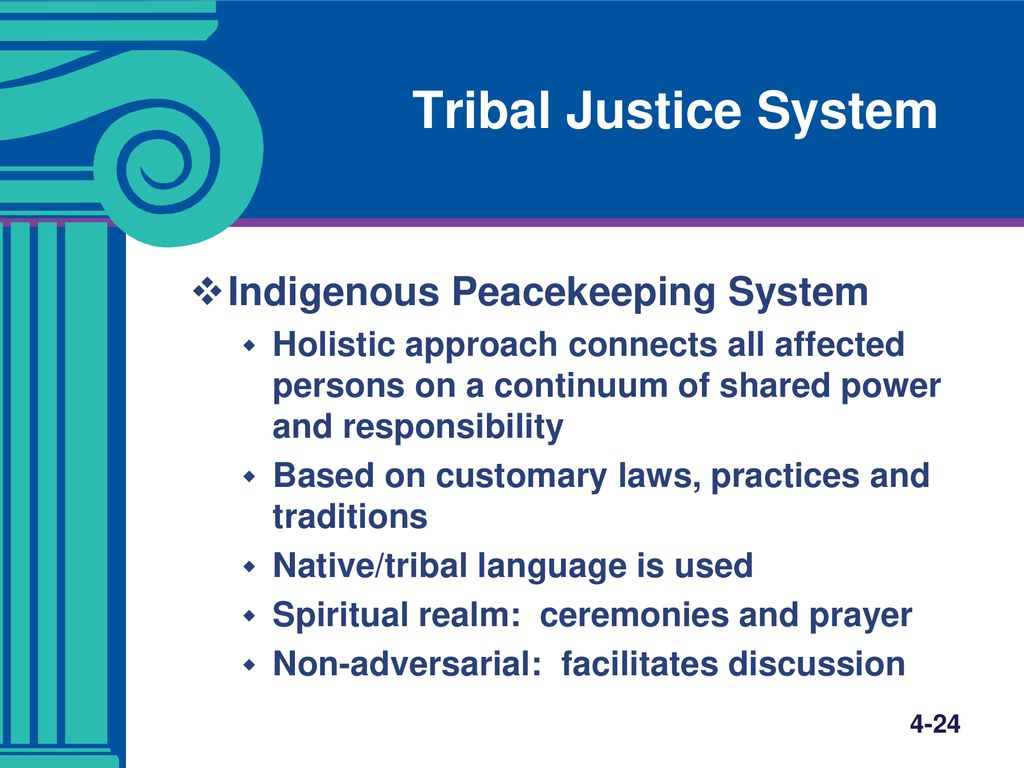

Before European contact, Indigenous justice systems varied widely, reflecting the unique societal structures of hundreds of distinct nations. Yet, common threads emerged: an emphasis on restoring balance, repairing harm to the victim and community, and integrating offenders back into the social fabric. Punishment, as understood in Western terms, was often secondary to reconciliation. For many Plains tribes, for instance, an offender might be tasked with making reparations to the victim’s family, or undergoing spiritual purification. Among the Iroquois, council meetings and consensus-building were paramount, with elders guiding discussions toward resolutions that prioritized the collective good. These systems were intrinsically linked to spiritual beliefs, the natural world, and a profound respect for communal harmony.

The advent of colonization, however, brought a relentless assault on these established traditions. The United States government, through a series of policies ranging from forced assimilation to outright land theft, systematically undermined tribal sovereignty and, by extension, tribal justice. The Major Crimes Act of 1885 stripped tribes of jurisdiction over serious felonies committed by Indians in Indian Country, transferring it to federal courts. This was followed by Public Law 280 in 1953, which unilaterally transferred criminal and, in some cases, civil jurisdiction over reservations to certain states, further eroding tribal authority. These legislative actions, born of a paternalistic view that tribal governments were incapable of self-governance, inflicted immense damage, creating jurisdictional vacuums and fostering a dependence on external legal systems that often failed to understand or respect Indigenous cultures.

Despite these challenges, the spirit of tribal justice endured. The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 marked a turning point, encouraging tribes to adopt constitutions and establish their own court systems. This legislative shift, coupled with the self-determination era of the 1970s, spurred the growth of modern tribal courts. Today, over 300 tribal courts operate across the United States, ranging from informal courts staffed by lay judges to highly formalized systems with professional judges, prosecutors, defense attorneys, and appellate review.

These modern tribal courts are remarkable for their hybrid nature. While many have adopted aspects of Anglo-American legal procedure – such as due process, rules of evidence, and adversarial proceedings – they often retain and actively integrate traditional values. "Healing to Wellness Courts," for example, are a prime example of this synthesis. Modeled after drug courts, they incorporate traditional practices like talking circles, elder guidance, and spiritual ceremonies into a therapeutic approach to address addiction and related offenses. Instead of purely punitive measures, these courts focus on rehabilitation, cultural reconnection, and community support, mirroring the restorative principles of pre-contact justice. As one tribal judge noted, "Our goal isn’t just to punish, but to heal the individual and, by extension, the community. That’s a profound difference from most Western legal systems."

However, the path of modern tribal courts is fraught with complex jurisdictional challenges, often a legacy of historical federal policies. A pivotal moment came with the 1978 Supreme Court decision in Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, which held that tribal courts lack inherent criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians, even for crimes committed within reservation boundaries. This ruling created a dangerous jurisdictional gap, particularly in areas with significant non-Native populations or "checkerboard" reservations where tribal and fee-simple lands are interspersed. The consequence was that non-Native offenders could often commit crimes against Native people on reservations with impunity, as state and federal authorities frequently lacked the resources or inclination to prosecute minor offenses, and tribal courts were legally barred from doing so.

This gap was starkly illustrated in the epidemic of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW), where perpetrators, often non-Native, escaped justice due to jurisdictional ambiguities. Recognizing this egregious injustice, Congress took a significant step in 2013 by reauthorizing the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA). This reauthorization included a crucial provision that restored tribal criminal jurisdiction over non-Indian perpetrators of domestic violence, dating violence, and violations of protection orders committed against Native Americans in Indian Country. While a monumental victory for tribal sovereignty and safety, this jurisdiction is still limited to specific crimes and requires tribes to meet certain due process standards, highlighting the ongoing struggle for full and inherent jurisdictional authority.

Beyond criminal matters, tribal courts also exercise civil jurisdiction over a wide array of issues, including family law, child welfare (often under the Indian Child Welfare Act, ICWA), land disputes, business regulations, and torts within their territories. Their role in upholding tribal sovereignty is critical, serving as the judicial branch of self-governing nations. They interpret tribal codes, resolve disputes, and ensure the enforcement of laws that reflect the unique cultural norms and aspirations of their people.

Despite their vital function, tribal justice systems often face chronic underfunding. Federal support, though increasing in recent years, remains insufficient to meet the extensive needs of courts serving vast and often remote communities. This underfunding impacts everything from judicial salaries and court infrastructure to the availability of legal aid for indigent defendants. Many tribal courts rely on lay advocates rather than licensed attorneys, a practical solution born of necessity, but one that can raise questions about the quality of legal representation.

Looking ahead, the evolution of tribal justice systems is a testament to Indigenous resilience and self-determination. The ongoing push for enhanced jurisdiction, particularly in areas like drug offenses and other serious crimes, continues to be a priority for many tribes. The development of inter-tribal courts and regional justice centers also offers promising avenues for resource sharing and greater efficiency. The unique blend of traditional wisdom and modern legal frameworks found in tribal courts not only serves the immediate needs of Native communities but also offers valuable lessons to the broader legal world – lessons in restorative justice, community engagement, and the profound power of cultural preservation in the pursuit of true justice.

In essence, Native American tribal justice systems stand as living embodiments of sovereignty. They are dynamic institutions, constantly adapting to protect their people, heal their communities, and honor the ancestral paths of justice, offering a compelling vision for a more holistic and culturally informed approach to law and order.