Beyond Stereotypes: The True Meaning of Mohawk Hairstyles in Kanien’kehaka Culture

The image is ubiquitous: a strip of hair running down the center of the head, sides shaved clean. For many, it’s a rebellious statement, a punk rock emblem, or a fleeting fashion trend. This hairstyle, widely known as the "Mohawk," has permeated global pop culture, becoming a symbol far removed from its origins. Yet, this widespread adoption is a profound act of cultural appropriation, stripping a deeply sacred and significant cultural expression from its true home. To understand the "Mohawk" haircut is to look beyond the superficial, beyond the stereotypes, and delve into the rich, complex tapestry of Kanien’kehaka (Mohawk) culture, where it is not merely a style, but a powerful symbol of identity, spirituality, and sovereignty.

The people commonly referred to as "Mohawk" are, in their own language, the Kanien’kehaka – "People of the Flint." They are one of the original five nations of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, known as the "Keepers of the Eastern Door," guardians of the confederacy’s eastern territories. Their history stretches back millennia, predating colonial encounters by centuries. The hairstyle that has captured the world’s imagination is not, and never was, a mere fashion statement for the Kanien’kehaka. Its roots are firmly planted in a traditional context, often linked to the Gus-toh-weh, the traditional feathered headdress worn by Haudenosaunee men, and the warrior spirit.

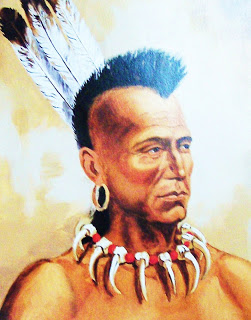

Historically, the hair was meticulously styled to complement and support the Gus-toh-weh. While Western narratives often sensationalized a "scalp-lock" or "warrior’s braid" as an invitation for battle, the truth is far more nuanced and spiritual. For the Kanien’kehaka and other Haudenosaunee nations, hair holds profound spiritual significance. It is often considered an extension of one’s thoughts, spirit, and connection to the Creator. The specific styling, often a narrow strip or a braided lock, was not a universal everyday look, but rather a ceremonial or war-ready presentation that would facilitate the wearing of the Gus-toh-weh and represent specific cultural values. The feathers on the Gus-toh-weh themselves held specific meanings; for example, the Kanien’kehaka Gus-toh-weh features three upright eagle feathers, distinguishing it from other nations within the Confederacy. The hair underneath was often shaved or plucked on the sides, leaving a central strip or lock that was sometimes braided, sometimes left loose, or sometimes stiffened to stand erect, providing a base for the headdress and symbolizing preparedness and a distinct identity.

This traditional style was not about rebellion, but about adherence to cultural norms and spiritual beliefs. It signified a commitment to one’s community, one’s heritage, and one’s role within the Haudenosaunee worldview. It was a visual marker of who they were – the Kanien’kehaka, strong, resilient, and deeply connected to their ancestral lands and traditions. Elders and cultural educators emphasize that the way hair is kept and presented is a testament to one’s respect for oneself and one’s people. As one Kanien’kehaka cultural keeper might articulate, "Our hair is not just hair; it is a connection to our ancestors, to the land, and to the Creator. It is a part of our spirit, a visual prayer."

The radical transformation of this sacred symbol began with colonial encounters. European observers, often misunderstanding or deliberately misrepresenting Indigenous cultures, sensationalized the hairstyle. It was depicted in paintings and narratives as savage, primitive, and a marker of "wild" Indigenous peoples. This misinterpretation served a colonial agenda, justifying land theft and cultural suppression by dehumanizing the Indigenous inhabitants. The term "Mohawk" itself is an exonym, derived from an Algonquian word meaning "man-eaters" or "flint-gatherers," a name imposed upon them rather than their own self-identification as Kanien’kehaka. This external naming, coupled with the distorted portrayal of their appearance, laid the groundwork for future appropriation.

The true "Mohawk" moment in Western pop culture arrived in the 1970s with the rise of punk rock. Seeking to shock and defy mainstream norms, punk musicians and their followers adopted the dramatic, shaved-sides-and-central-strip hairstyle. It was edgy, confrontational, and visually arresting. From this point, the "Mohawk" became detached from its origins, transforming into a generic symbol of rebellion, an aesthetic divorced from its cultural and spiritual roots. It was commodified, appearing in fashion magazines, on celebrities, and eventually trickling down into mainstream trends. The irony is stark: a style born of deep cultural meaning and resilience was co-opted by a movement seeking counter-cultural identity, entirely oblivious to (or simply disregarding) the profound history it was stripping away.

This appropriation is not harmless. It perpetuates a cycle of erasure, where Indigenous contributions are taken, rebranded, and celebrated without acknowledging the source, often while the original creators continue to face systemic discrimination and struggle for recognition. When someone wears a "Mohawk" haircut as a fashion statement, they inadvertently (or consciously) participate in this erasure. They benefit from the visual impact of the style without bearing any of the historical burdens or responsibilities that come with its true meaning. It trivializes centuries of cultural practice, reducing a powerful symbol of identity and spirituality to a mere aesthetic choice. "When people wear it without understanding, they are essentially wearing a caricature of our identity," states a prominent Indigenous advocate. "It’s a form of cultural theft that further marginalizes us."

Today, many Kanien’kehaka and other Indigenous peoples are actively working to reclaim and revitalize their cultural practices, including the traditional significance of their hairstyles. For Kanien’kehaka youth, wearing their hair in traditional styles – whether it’s a modern interpretation of the central strip or long, braided hair – is an act of defiance against cultural appropriation and a powerful affirmation of their identity. It is a visible statement of pride, resilience, and connection to their ancestors and future generations. It’s a way of saying, "We are still here, our culture is vibrant, and our traditions are sacred." Educational initiatives, cultural workshops, and community gatherings are vital spaces where the true meaning of these practices is taught and celebrated, ensuring that the next generation understands the depth of their heritage.

Understanding the "Mohawk" hairstyle truly means understanding the Kanien’kehaka worldview. It’s about respecting their sovereignty, their history, and their ongoing struggles for self-determination. It demands acknowledging that Indigenous cultures are living, breathing entities, not relics of the past to be plundered for aesthetic trends. It requires listening to Indigenous voices, learning from their perspectives, and actively challenging the stereotypes that have been imposed for centuries. The hair is but one element in a vast and intricate cultural system that includes language, ceremonies, governance, and a profound relationship with the land.

In conclusion, the popular "Mohawk" hairstyle is a powerful example of how a sacred cultural expression can be distorted and commodified, losing its essence in the process. For the Kanien’kehaka people, the traditional hairstyle is far more than a visual statement; it is a spiritual anchor, a mark of identity, a connection to ancestors, and a symbol of enduring resilience. As we navigate an increasingly interconnected world, it is imperative to move beyond superficial interpretations and engage with the true meanings embedded within Indigenous cultures. To truly appreciate the "Mohawk" is to honor its Kanien’kehaka origins, acknowledge the harm of appropriation, and support the ongoing efforts of Indigenous peoples to reclaim, celebrate, and educate the world about their profound and vibrant heritage. Only then can we move towards a more respectful and equitable understanding of cultural diversity.