The Enduring Dome: Wichita Grass House Building – Traditional Architecture of the Southern Plains

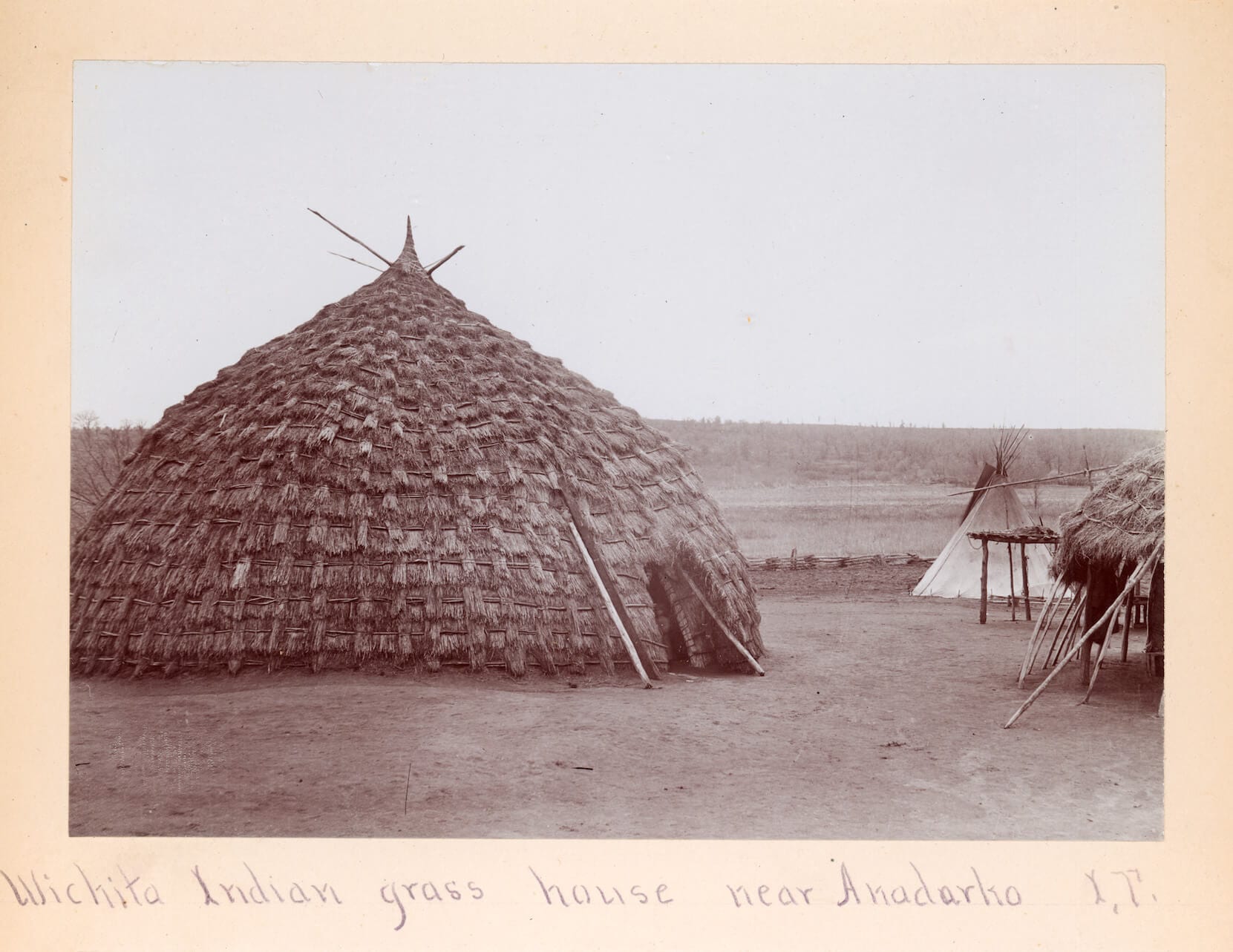

On the vast, windswept plains of what is now Oklahoma, a unique architectural marvel once stood as a testament to indigenous ingenuity and harmonious living: the Wichita Grass House. Far removed from the popular image of tipis defining Plains Indian dwellings, these formidable, dome-shaped structures, known to the Wichita as "Takhoma" or "Chiri-ki," represented a sophisticated understanding of engineering, material science, and environmental adaptation. More than mere shelters, they were enduring symbols of community, sustenance, and a deeply rooted agricultural lifestyle, offering lessons in sustainable building that resonate even today.

The Wichita people, along with their Caddoan linguistic relatives like the Pawnee and Kitsai, were distinct from their nomadic neighbors. While tribes like the Lakota and Cheyenne followed buffalo herds, the Wichita were sedentary farmers, cultivating corn, beans, and squash along river valleys. This agricultural base necessitated permanent, robust dwellings, and their answer was the grass house – a structure perfectly suited to the extremes of the Southern Plains climate, from scorching summers to biting winters and violent thunderstorms. These houses were not just functional; they were the heart of Wichita villages, centers of family life, and expressions of cultural identity.

The construction of a Wichita Grass House was a monumental communal effort, often involving the entire village. It was a process steeped in tradition, passed down through generations, and required a profound understanding of natural materials. The primary structural components were harvested from the immediate environment, showcasing an unparalleled connection to the land.

The frame, the skeleton of these impressive domes, was typically constructed from the incredibly strong and resilient wood of the Osage Orange tree, often called Bois d’Arc (bow-wood) by early French settlers due to its suitability for crafting powerful bows. This wood, known for its exceptional resistance to rot and insect damage, provided the necessary rigidity and flexibility. Other woods like willow or elm were also utilized, depending on availability. These slender yet robust poles were carefully selected, stripped of their bark, and then bent and interwoven to form the characteristic beehive or dome shape. The primary supports, often four to eight large posts, were set deep into the ground, forming a central square or circle. Ring beams connected these main posts, and then countless smaller poles were lashed in an intricate lattice pattern, creating a self-supporting, incredibly strong framework. The ingenious design relied on tension and compression, distributing weight evenly and allowing the structure to withstand the fierce winds that frequently swept across the plains.

Once the frame was meticulously erected, the house truly began to take its "grass" form. The primary thatching material was bundles of tall, coarse grasses, predominantly Big Bluestem, Switchgrass, and Little Bluestem. These grasses, abundant in the prairies, were harvested in late summer or early fall when they were dry and tough. The harvesting itself was an arduous task, often done by women, who would cut, gather, and bundle thousands upon thousands of individual stalks. These bundles, often a foot or more in diameter, were then carefully prepared for attachment.

The actual thatching process was a meticulous, layer-by-layer operation. Starting from the bottom, bundles of grass were securely tied to the wooden frame using thin willow branches, rawhide strips, or other strong plant fibers. Each successive layer overlapped the one below, much like shingles on a modern roof, creating an impenetrable barrier against rain, wind, and sun. The layers were often a foot to eighteen inches thick, providing exceptional insulation. This dense blanket of grass was not only waterproof but also remarkably effective at regulating interior temperatures, keeping the house cool in the summer heat and warm during the frigid winter months. At the apex of the dome, a smoke hole was left open, often covered by a removable cap, to allow smoke from the central hearth to escape and provide ventilation. The doorway, typically facing east to greet the rising sun, was often a low, tunnel-like entrance, sometimes covered with a hide flap for added privacy and protection from the elements.

The engineering brilliance of the grass house extended beyond its materials and construction. Its dome shape was inherently aerodynamic, allowing winds to flow smoothly over its surface rather than creating points of high pressure that could tear it apart. The thick grass walls provided excellent thermal mass, absorbing heat during the day and radiating it slowly at night, or vice-versa, maintaining a stable internal climate. The steep pitch of the dome ensured rapid water runoff, preventing saturation and prolonging the life of the thatch. These structures were remarkably resilient, often standing for decades with proper maintenance, a testament to their skilled builders.

Life inside a grass house was a testament to the Wichita’s communal spirit. The interior was spacious, often 20 to 50 feet in diameter, accommodating extended families. The central hearth, perpetually burning, served as the focal point for cooking, warmth, and storytelling. Sleeping platforms, raised off the ground to avoid dampness and provide storage underneath, lined the perimeter. Personal belongings, tools, and food stores were neatly organized within the dwelling. Despite the seemingly rustic materials, the interior was a place of comfort, warmth, and bustling activity, reflecting a highly organized and culturally rich society.

The arrival of European settlers brought profound changes to the Wichita way of life, and with it, the decline of grass house construction. Loss of land, forced relocation, the introduction of new building materials, and the pressures of assimilation policies all contributed to the fading of this traditional architectural practice. By the early 20th century, very few grass houses were still being built or maintained, and the knowledge of their intricate construction began to dwindle.

However, the enduring legacy of the Wichita Grass House has not been forgotten. In recent decades, there has been a significant and inspiring revival of interest and effort to reconstruct these traditional dwellings. The Wichita and Affiliated Tribes, headquartered in Anadarko, Oklahoma, have spearheaded initiatives to preserve and revitalize their cultural heritage. Reconstruction projects at sites like the Wichita Tribal Complex, the Museum of the Great Plains in Lawton, Oklahoma, and Fort Sill, serve not only as historical markers but also as vital educational tools. These efforts involve extensive research, studying historical accounts, photographs, and the few remaining archaeological traces. Crucially, they rely on the invaluable knowledge passed down by tribal elders, who, though they may not have built a full-sized house themselves, retain memories, stories, and the understanding of the principles and techniques involved.

Rebuilding a grass house today is a meticulous endeavor, often a multi-year project, requiring the same community spirit and dedication as in centuries past. It is a powerful act of cultural reclamation, connecting contemporary generations with their ancestors and providing a tangible link to a rich architectural past. These reconstructed houses are more than just exhibits; they are living classrooms, demonstrating the ingenuity, resilience, and profound environmental wisdom of the Wichita people. They remind us that sustainable architecture is not a modern invention but a timeless practice, perfected by indigenous cultures who understood how to live in balance with their environment.

The Wichita Grass House stands as a powerful symbol of indigenous architectural genius on the Southern Plains. It challenges preconceived notions of "primitive" dwellings, revealing instead a sophisticated understanding of engineering, thermal dynamics, and material science. It is a testament to the Wichita people’s ability to thrive in a challenging environment, building homes that were not only functional and durable but also deeply intertwined with their cultural identity and agricultural way of life. In an age grappling with environmental concerns and the search for sustainable living, the enduring dome of the Wichita Grass House offers timeless lessons from the earth, reminding us of the profound wisdom embedded in traditional architecture. Its continued revival ensures that this remarkable piece of cultural heritage will inspire and educate for generations to come.