The Unyielding Thirst: Native American Water Rights and the Fight for Survival

Water, in its purest essence, is life. For Native American tribes across the United States, it is also a birthright, a treaty obligation, a cultural cornerstone, and, tragically, a relentless battleground. While much of the nation takes readily available clean water for granted, many Indigenous communities face a stark reality: unreliable access, contaminated sources, and the systemic denial of their ancestral water rights, threatening their health, sovereignty, and very existence. This isn’t merely an environmental issue; it is a profound matter of justice, a testament to unfulfilled promises, and a critical challenge demanding immediate attention.

Over 3.3 million Native Americans reside on reservations, many in arid regions where water is a precious commodity. Despite often holding senior water rights – rights that predate most non-Native claims – tribes are frequently the last to receive water, if they receive it at all. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reports that Native Americans are 19 times more likely than white Americans to lack indoor plumbing and safe drinking water. This shocking disparity underscores a crisis that is both historical and deeply contemporary, rooted in the legal complexities of reserved rights, the economic pressures of surrounding non-Native development, and the enduring legacy of colonialism.

The Bedrock of Rights: The Winters Doctrine and the Trust Responsibility

The legal foundation for Native American water rights rests primarily on the "reserved rights doctrine," famously established in the 1908 Supreme Court case Winters v. United States. The Court ruled that when Congress established reservations, it implicitly reserved enough water to fulfill the purposes for which the reservation was created – primarily to enable the tribes to establish permanent, agricultural homelands. These "Winters rights" are unique because they are "time immemorial" – they date back to the creation of the reservation, often predating non-Native water claims based on the "prior appropriation" doctrine (first in time, first in right).

This distinction is crucial. While states typically allocate water based on who used it first, Winters rights are often senior to nearly all other claims in a basin. However, the Winters doctrine merely establishes the existence of these rights; it does not quantify them. The process of quantifying and enforcing these rights has become a century-long saga of litigation, negotiation, and political struggle.

Further complicating matters is the federal government’s "trust responsibility" to Native American tribes. Stemming from treaties and statutes, this responsibility obligates the U.S. government to protect tribal assets, including their land and water resources. Yet, time and again, the federal government has been criticized for failing to adequately defend tribal water rights, often prioritizing non-Native interests or simply lacking the political will and financial resources to fulfill its duties.

The Human Cost: A Crisis of Access and Health

The abstract legal battles translate directly into profound human suffering. On many reservations, a significant portion of the population lacks access to clean, running water. Imagine waking up every day and knowing you must haul water for drinking, cooking, and hygiene – sometimes for miles – or rely on unsafe, contaminated sources.

The Navajo Nation, the largest reservation in the U.S., provides a stark example. Over 30% of Navajo homes lack running water, a number comparable to some developing nations. Decades of uranium mining on the reservation, often conducted by corporations with federal approval, have left a devastating legacy of contaminated water sources. Abandoned mines leach heavy metals and radiation into groundwater, leading to elevated rates of kidney disease, cancer, and other severe health issues among the Navajo people. Efforts to address this contamination have been slow and insufficient, leaving communities to grapple with poisoned wells and dry taps.

"Water is a fundamental human right, not a privilege," states Crystal Cavalier-Keck (Occaneechi Band of the Saponi Nation), a prominent water protector. "Yet, for our people, it’s a daily fight just to access something that the rest of America takes for granted. It’s an environmental injustice that directly impacts our health and our future."

Beyond direct contamination, the sheer lack of infrastructure is crippling. Many reservations simply don’t have the necessary pipes, pumps, and treatment facilities to deliver water to homes. This forces residents to buy expensive bottled water, rely on cisterns filled by truck deliveries, or use communal spigots – all precarious and often unsanitary solutions. The health consequences are dire, contributing to higher rates of preventable diseases and creating significant economic burdens on already impoverished communities.

Economic Stagnation and Cultural Erosion

Secure water rights are not just about drinking water; they are fundamental to economic development. Without reliable water, tribes struggle to pursue agriculture, develop industries, or attract businesses. How can a tribe plan for a sustainable future if the most basic resource is uncertain? The potential for self-sufficiency and economic growth is stifled, perpetuating cycles of poverty and dependence.

Water also holds immense cultural and spiritual significance for Native American tribes. It is central to ceremonies, traditional practices, and the very identity of many Indigenous peoples. The drying up of sacred springs, the pollution of ancestral rivers, or the inability to access water for traditional farming methods represents a profound loss – a severing of connection to land, heritage, and spirituality.

Consider the Klamath Basin in Oregon and California, where the Klamath Tribes have fought for decades to protect water flows essential for their traditional salmon fisheries. The salmon are not just a food source; they are central to the tribes’ spiritual beliefs and cultural practices. However, competing demands from non-Native irrigators, environmentalists, and federal agencies have led to repeated water crises, devastating salmon runs and placing immense stress on the tribal community. The legal battles here highlight the complex interplay of ecological needs, economic livelihoods, and treaty obligations.

The Colorado River Basin: A New Chapter in Tribal Advocacy

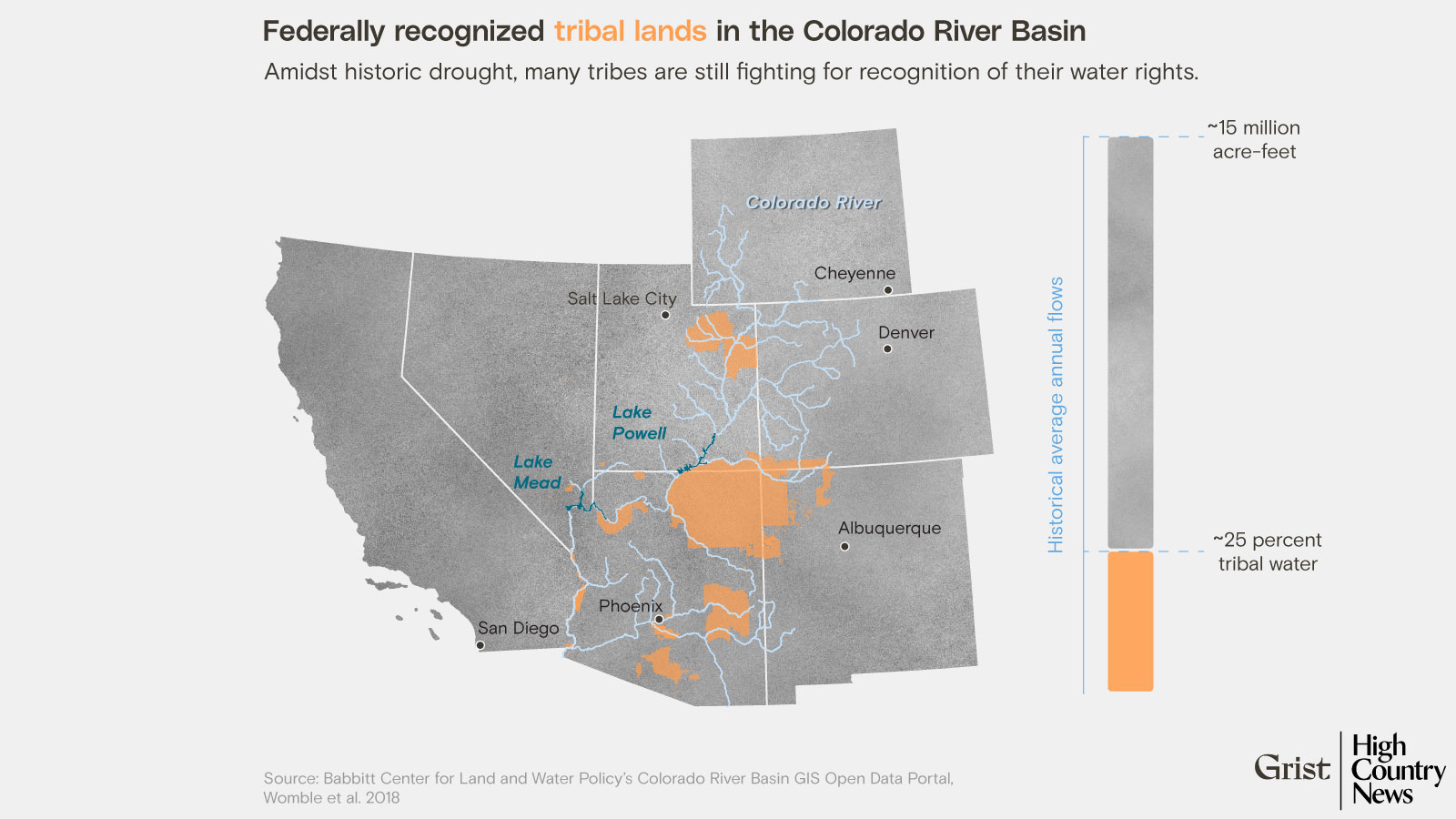

The Colorado River Basin, a lifeline for 40 million people across seven states, is facing unprecedented drought and over-allocation. Historically, Native American tribes with significant water rights in the basin – collectively holding rights to an estimated 2.9 million acre-feet of water, more than any single state – have been largely excluded from the negotiations and management of this vital resource.

However, this is beginning to change. As the river shrinks, the critical role of tribal water rights is becoming undeniable. Tribes like the Colorado River Indian Tribes (CRIT), the Fort Mojave Indian Tribe, and the Navajo Nation are asserting their long-dormant Winters rights, demanding a seat at the table, and offering innovative solutions for conservation and management. Their involvement is not just about securing their own water; it’s about bringing a deep understanding of sustainable resource management and a long-term perspective to a basin facing existential threats. This marks a pivotal shift, moving from passive recipients of federal policies to active, sovereign players in regional water governance.

The Path Forward: Settlement, Investment, and Self-Determination

The challenges are immense, but pathways to justice exist.

-

Negotiated Settlements: Litigation is costly, time-consuming, and adversarial. Negotiated water rights settlements, though complex and requiring substantial federal funding, offer a more collaborative path. They involve tribes, states, and the federal government coming to an agreement on the quantification and allocation of tribal water rights. The Arizona Water Settlements Act of 2004, which resolved long-standing water claims for several Arizona tribes, is an example of a successful, albeit lengthy, process. These settlements provide certainty, unlock funding for critical infrastructure, and allow tribes to finally utilize their reserved rights.

-

Infrastructure Investment: The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, passed in 2021, allocated significant funding ($3.5 billion) for Indian Water Rights Settlements and related infrastructure. This is a crucial step, but sustained investment is needed to address the massive backlog of infrastructure needs on reservations. Pipelines, water treatment plants, and distribution systems are essential to translate legal rights into tangible access.

-

Tribal Self-Determination and Management: Tribes are often the most knowledgeable and invested stewards of their lands and waters. Empowering them with the resources and authority to manage their own water resources, consistent with their cultural values and legal rights, is paramount. This includes funding for tribal water departments, technical assistance, and support for developing their own water codes and regulations.

-

Collaboration and Education: Fostering genuine collaboration between tribal nations, states, federal agencies, and non-Native water users is vital. This requires mutual respect, understanding of diverse perspectives, and a willingness to find common ground. Educating the broader public about the history and significance of Native American water rights is also critical to building support for equitable solutions.

The fight for Native American water rights is more than a legal or environmental battle; it is a struggle for self-determination, health, and cultural survival. It is a stark reminder that the promises made to Indigenous peoples must be honored, not just on paper, but in the flowing rivers, the clean wells, and the thriving communities they support. As climate change intensifies and water scarcity becomes a global concern, the wisdom of Indigenous water stewardship and the imperative of respecting their inherent rights offer not just a path to justice, but a blueprint for a more sustainable future for all. The unyielding thirst of Native American communities demands an unyielding commitment to justice.