High Deserts, Deep Roots: Central Arizona’s Enduring Saga of Adaptation and History

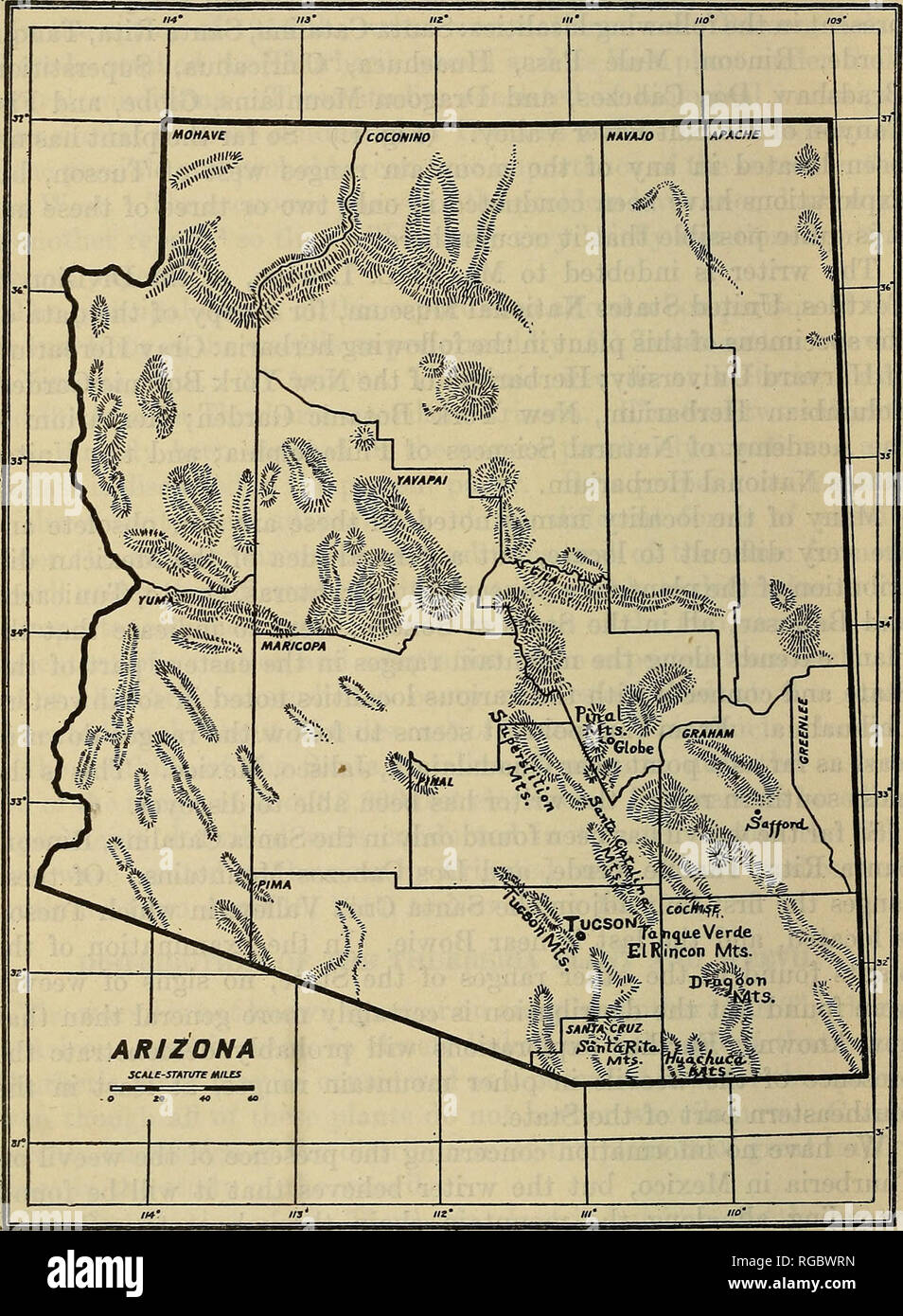

The rugged heart of Arizona, a sprawling expanse where the Sonoran Desert gives way to elevated plateaus and sky-scraping peaks, is more than just a landscape; it is a profound testament to adaptation. From the formidable Mogollon Rim slicing across the state to the ancient Bradshaw and Mazatzal Mountains, this central Arizona highland region has for millennia served as a crucible, forging resilience in every living thing that calls it home. Its history is etched not only in the dramatic geology but in the enduring spirit of its inhabitants, both human and wild, who have ceaselessly adapted to its often-harsh beauty.

Geologically, Central Arizona is a masterpiece of dynamic forces. The colossal Mogollon Rim, a 200-mile-long escarpment, dramatically marks the southern edge of the Colorado Plateau, showcasing a sheer drop of thousands of feet that exposes layers of geological time. This dramatic uplift and subsequent erosion, coupled with ancient volcanic activity, has sculpted a terrain of deep canyons, towering peaks, and verdant plateaus that belie the arid reputation of the state. It is a region where water, though often scarce, has carved out life-sustaining oases, and where elevation dictates a radical shift in climate, supporting an extraordinary diversity of ecosystems, from chaparral and juniper woodlands to vast Ponderosa pine forests.

For thousands of years before European contact, indigenous peoples were the original, and arguably most sophisticated, adapters to this complex environment. Cultures such as the Sinagua, Salado, and Ancestral Puebloans, and later the Yavapai and Apache, developed intricate systems for survival. They were masters of dryland agriculture, building sophisticated check dams and terraces to capture precious runoff for crops like corn, beans, and squash. Their settlements, often ingeniously carved into cliff faces or built strategically near perennial water sources, like Tuzigoot and Montezuma Castle, stand as silent monuments to their architectural prowess and deep understanding of the land.

Their adaptation extended beyond mere survival; it was a profound cultural and spiritual integration with the environment. They harvested wild foods with an intimate knowledge of seasonal cycles – mesquite beans, prickly pear, and especially agave, which was roasted in massive pits, providing both sustenance and fiber. "The land speaks to those who listen," an adage often attributed to indigenous wisdom, perfectly encapsulates their relationship with this landscape. Their trails, their tools, their oral histories – all speak of a people who thrived not by conquering nature, but by harmonizing with its rhythms, developing a sustainable way of life that endured for centuries amidst the challenging terrain and climatic extremes.

The arrival of European and American explorers, prospectors, and settlers in the 16th to 19th centuries introduced a new chapter of adaptation, often marked by conflict and drastic transformation. While Spanish influence was limited to the fringes, the mid-19th century American push westward brought a wave of miners drawn by the promise of gold and silver in the Bradshaw Mountains and copper in places like Jerome. These pioneers faced extreme isolation, harsh weather, and the ever-present threat of conflict with the Apache and Yavapai, who fiercely defended their ancestral lands.

Settlers adapted by constructing resilient log cabins and stone buildings, diverting mountain streams for rudimentary irrigation, and developing new transportation routes through treacherous canyons. Towns like Prescott, established as the first territorial capital, sprang up amidst the pine forests, driven by the mining boom and ranching interests. This era was defined by a rugged individualism and a relentless pursuit of resources, often at great human and environmental cost. The Apache Wars, a brutal series of conflicts, epitomized the clash of cultures and competing visions for the land, leaving an indelible mark on the region’s history and leading to the eventual displacement of many indigenous communities.

Yet, the central Arizona mountains themselves continued their own, silent adaptations, a testament to ecological resilience. The transition zones are particularly fascinating. At lower elevations, plants like the resilient juniper and various species of agave demonstrate remarkable drought tolerance, storing water in fleshy leaves or deep root systems. As elevation increases, these give way to vast Ponderosa pine forests, whose thick, fire-resistant bark and serotinous cones (which release seeds only after intense heat) are adaptations to the region’s natural fire cycles. "Fire is not always the enemy," foresters now understand, acknowledging that controlled burns are vital for the health and regeneration of these ecosystems.

Animal life, too, exhibits incredible ingenuity. Mountain lions and black bears roam the higher elevations, adapting their hunting patterns to the seasonal availability of prey. Elk and deer migrate between higher summer pastures and lower winter ranges, while javelina, a pig-like mammal, thrive in the lower chaparral, utilizing succulent plants for both food and moisture. Birds like the Steller’s Jay and various raptors are perfectly suited to the pine forests, while smaller reptiles and amphibians find niches in the diverse microclimates created by the varied topography. Each species is a finely tuned instrument, playing its part in the intricate symphony of the mountain ecosystem.

In the modern era, adaptation in Central Arizona takes on new dimensions. The region has become a recreational haven, attracting hikers, campers, and skiers to its cooler climates and scenic beauty. This has necessitated adaptations in infrastructure, from ski resorts near Flagstaff to extensive trail systems and campgrounds. However, it also brings new pressures. Urbanization, particularly around the fringes of cities like Prescott and Payson, encroaches on wildlife habitats and increases demand for the region’s already strained water resources. The delicate balance between development and preservation has become a defining challenge.

Perhaps the most significant contemporary adaptation required is in response to climate change. Central Arizona is on the front lines, experiencing increased temperatures, prolonged droughts, and a growing frequency and intensity of wildfires. Communities are adapting through advanced forest management techniques, creating defensible spaces, and investing heavily in fire suppression. Water conservation has become paramount, with innovative strategies for groundwater management and efficient agricultural practices. The future of these mountains, and the communities that depend on them, hinges on our collective ability to adapt quickly and effectively to these profound environmental shifts.

The Central Arizona mountains, with their dramatic geology and rich tapestry of life, remain an enduring testament to the power of adaptation. From the ancient indigenous peoples who understood its every nuance, to the rugged pioneers who carved out a living, and to the modern residents grappling with environmental challenges, the story of this region is one of continuous change and resilient response. It is a landscape that demands respect, fosters innovation, and perpetually reminds us that survival is not about conquering, but about harmonizing with the profound forces of nature. The deep roots of its history continue to nourish new forms of adaptation, ensuring that the saga of Central Arizona’s mountains will endure for generations to come.