Weaving Wisdom: The Embodiment of Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Indigenous Craft

Indigenous craft is not merely an aesthetic pursuit or a utilitarian endeavor; it is a profound repository of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), a living testament to centuries of intimate connection between people and their environment. Far from being simple decorative objects, these creations – be they baskets, textiles, pottery, carvings, or tools – embody a sophisticated understanding of ecosystems, material science, and sustainable resource management, passed down through generations. This article delves into how TEK is meticulously woven into the fabric, form, and function of Indigenous crafts, highlighting their enduring relevance as both cultural anchors and vital blueprints for ecological stewardship.

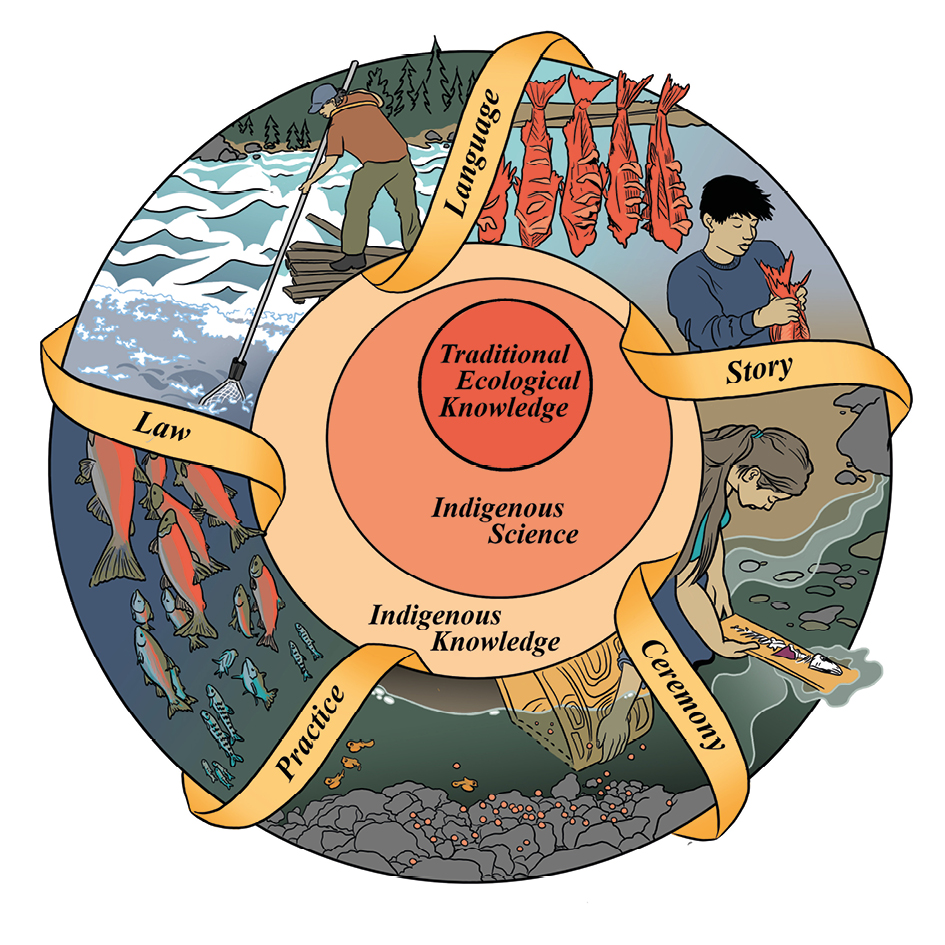

At its core, TEK is a cumulative body of knowledge, practice, and belief, evolving by adaptive processes and handed down through generations by cultural transmission, about the relationship of living beings (including humans) with their traditional group and with their environment. It is holistic, recognizing the interconnectedness of all life, and emphasizes reciprocity and respect for the natural world. Indigenous craft, therefore, serves as a tangible expression of this worldview, where every choice, from material selection to design motif, is informed by a deep ecological literacy.

The Art of Sustainable Sourcing: A Foundation of TEK

The journey of an Indigenous craft begins long before its creation, with the careful and respectful sourcing of materials. This is perhaps the most direct manifestation of TEK. Artisans possess an encyclopedic knowledge of their local flora and fauna: which plants yield the strongest fibers, the most vibrant dyes, or the most durable wood; which animals provide the best hides or sinews; and where to find specific clays or stones. But this knowledge extends beyond mere identification. It encompasses when to harvest, how to harvest without harming the parent plant or ecosystem, and how much to take to ensure future abundance.

Consider the intricate basketry of the Pacific Northwest, crafted from cedar bark, spruce root, or bear grass. Harvesters, often elder women, know precisely which part of the tree or plant to use, the optimal season for collection (often dictated by sap flow or plant flexibility), and specific techniques to peel bark or dig roots without girdling trees or depleting plant populations. For instance, the Squaxin Island Tribe’s basket weavers meticulously select cedar bark from specific trees, making cuts that allow the tree to heal and continue growing, ensuring a sustainable supply for generations. This practice reflects a core TEK principle: the land is not a resource to be exploited, but a relative to be nurtured.

Similarly, the materials for pottery, such as clay, temper (sand, crushed shells, volcanic ash), and natural pigments, are sourced with an understanding of their geological origins and properties. Pueblo potters, for example, have intimate knowledge of local clay beds, understanding which clays fire best at certain temperatures and how different additives affect porosity and strength. This nuanced understanding prevents over-extraction and ensures the quality and longevity of their work.

Design and Function: Ecosystems as Blueprints

The design and functional aspects of Indigenous crafts are often direct reflections of ecological adaptations and observations. Form follows function, but that function is often dictated by the specific environmental challenges and opportunities of a given landscape.

Take the iconic birchbark canoe of the Anishinaabe and other Northeastern Woodland tribes. Its design is a marvel of ecological engineering, utilizing lightweight, waterproof birchbark, flexible cedar ribs, and pine pitch sealant. The knowledge embedded in its construction – understanding the properties of different wood species, the elasticity of bark, and the natural waterproofing of resin – allowed for efficient travel across vast networks of lakes and rivers. This craft is a testament to observing natural buoyancy, material resilience against water and cold, and the ergonomic needs of paddlers, all derived from centuries of living within and adapting to their environment.

In the Arctic, Inuit communities craft anoraks and parkas from caribou or sealskin, meticulously sewn with sinew. The design is not just for warmth; it incorporates specific hood shapes to protect against wind, strategic seam placement to prevent water penetration, and layering techniques that trap air for insulation. These designs are born from an unparalleled understanding of extreme cold environments, animal physiology, and material science – knowledge honed through generations of survival and close observation of Arctic wildlife.

Even seemingly decorative patterns often carry ecological narratives or represent natural phenomena. Navajo (Diné) weavers incorporate intricate designs into their rugs, frequently depicting elements of their desert landscape – mountains, clouds, lightning, and animal tracks. These patterns are not abstract; they are visual stories of their homeland, their sacred connection to it, and their cosmology, reminding the weaver and viewer of the interconnectedness of all things within their natural world. The dyes used are often derived from local plants like indigo, cochineal, and various lichens, reflecting a precise TEK of plant chemistry and seasonal availability.

Techniques and Tools: Inherited Wisdom, Sustained Practice

The techniques and tools used in Indigenous craft are as much a part of TEK as the materials themselves. The processing of raw materials often involves complex, multi-stage processes that are ecologically informed. Tanning hides, for instance, a crucial skill across many Indigenous cultures, involves understanding the chemical properties of brains, smoke, or plant tannins to transform raw skin into soft, durable leather without the harsh chemicals used in modern industrial processes. This traditional method often utilizes local resources and returns organic matter to the earth, minimizing environmental impact.

The very tools of the trade are often crafted from natural materials, requiring their own set of TEK. Carving tools might be fashioned from stone, bone, or hardened wood, each material selected for its specific properties and sharpened using traditional methods. The knowledge of how to make and maintain these tools is itself a part of the craft, embodying a self-sufficient, localized economy that minimizes reliance on external, often resource-intensive, supply chains.

Spiritual Connection and Reciprocity: The Heart of TEK in Craft

Beyond the practical and functional, Indigenous craft is imbued with profound spiritual significance, reflecting the TEK principle of reciprocity. The act of gathering materials is often accompanied by prayers, offerings, and expressions of gratitude to the plant or animal spirit for its sacrifice. This practice acknowledges the sentience and spirit of the natural world and reinforces the ethic of taking only what is needed, and always giving back.

For many Indigenous peoples, the craft object itself is a living entity, carrying the spirit of the maker, the materials, and the land from which it came. A Haida argillite carving, for example, is not merely a depiction of a raven or a bear; it is a manifestation of the spirit of that creature, imbued with the sacred knowledge of the carver and the stories of the ancestors. The argillite itself, a rare black slate found only at Slatechuck Creek on Haida Gwaii, is treated with immense respect, its extraction governed by traditional protocols to ensure its long-term availability and spiritual integrity.

Challenges and Resilience: Protecting TEK in a Changing World

Today, the perpetuation of TEK in Indigenous craft faces significant challenges. Climate change directly impacts the availability and health of traditional materials – changing growing seasons for basketry plants, altering animal migration patterns for hunters, and threatening unique ecosystems. Colonial legacies, including the loss of traditional lands, forced assimilation, and the disruption of intergenerational knowledge transfer (such as through residential schools), have severed many Indigenous communities from their ecological heritage.

Furthermore, the commodification of Indigenous craft can sometimes lead to pressure for faster production or the use of cheaper, less sustainable materials, undermining the very TEK principles that define the art form. Cultural appropriation, where designs or motifs are used without permission or understanding, further erodes the cultural and ecological significance of these crafts.

Despite these challenges, Indigenous communities are demonstrating incredible resilience and innovation in revitalizing and protecting their TEK through craft. Language revitalization programs are reconnecting younger generations with the terminology and narratives surrounding their crafts. Master-apprentice programs are ensuring that complex skills and ecological knowledge are passed down. Artists are also adapting, finding sustainable alternatives to traditional materials when necessary, or using new technologies to document and share their knowledge, always rooted in their ancestral wisdom. Organizations like the Indian Arts and Crafts Board in the U.S. and various Indigenous-led initiatives worldwide work to promote ethical sourcing, fair trade, and cultural preservation.

Conclusion: A Global Lesson in Sustainable Living

Indigenous craft is far more than an artifact; it is an active testament to a worldview where humanity is inextricably linked to the natural world. Each basket, blanket, pot, or carving is a living document of Traditional Ecological Knowledge, embodying sophisticated scientific understanding, profound spiritual connection, and an unwavering commitment to sustainability.

In an era of unprecedented environmental crisis, the wisdom embedded in Indigenous craft offers invaluable lessons for all of humanity. It teaches us to observe, to listen, to respect, and to live in reciprocal relationship with the Earth. Supporting Indigenous artisans and recognizing the deep TEK within their creations is not just about appreciating art; it is about honoring a sustainable way of life, preserving vital ecological knowledge, and learning to weave our own future with wisdom and respect for the world around us. These crafts are not relics of the past; they are blueprints for a more sustainable and harmonious future.