The Golden Seed: How Indigenous Innovation Revolutionized Agriculture with Corn

In the annals of human history, few agricultural achievements rival the domestication and development of corn, or maize. Far from being a mere crop, corn stands as a monumental testament to indigenous ingenuity, a sophisticated feat of genetic engineering that transformed a humble wild grass into the cornerstone of civilizations across the Americas. This agricultural revolution, spearheaded by Mesoamerican peoples thousands of years ago, not only fed millions but also shaped cultures, economies, and entire landscapes, leaving an indelible legacy that continues to nourish the world today.

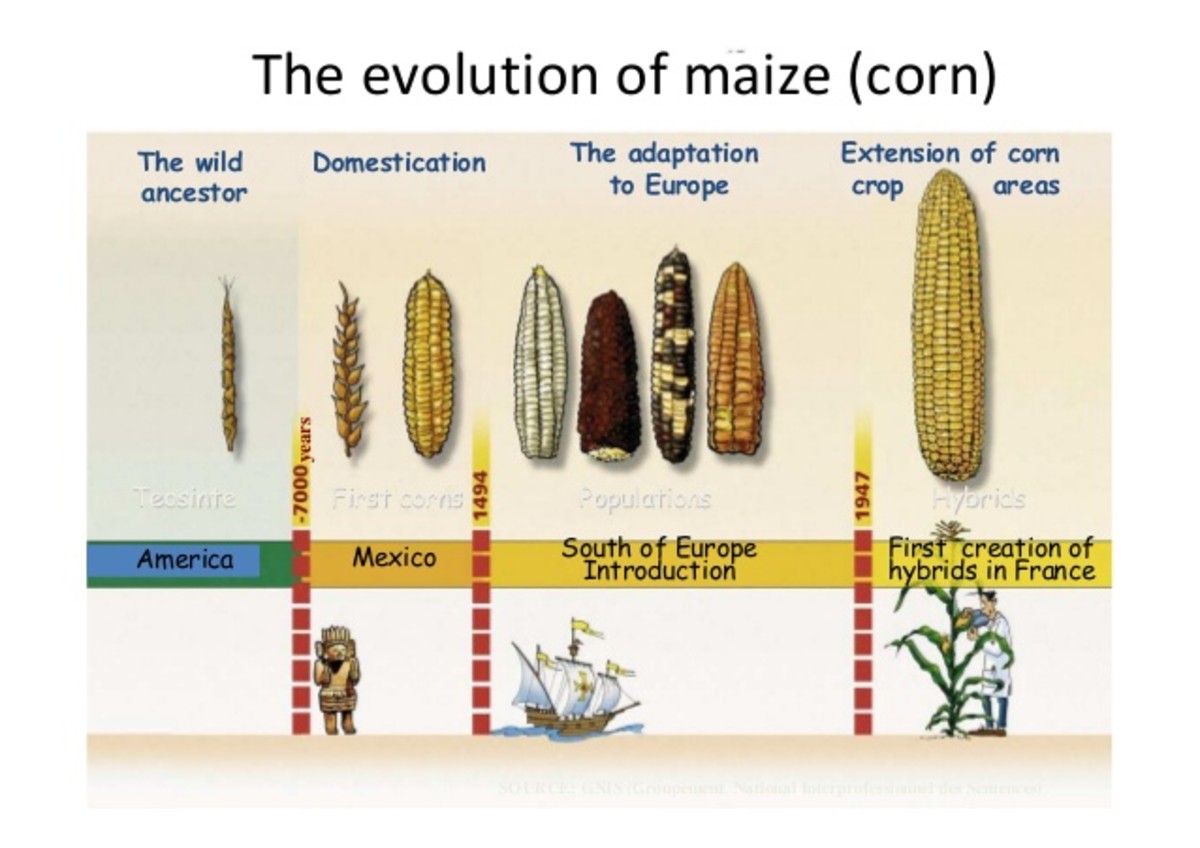

The story begins over 9,000 years ago in the Balsas River Valley of southwestern Mexico, with a wild, scraggly grass known as teosinte. To the untrained eye, teosinte offers little hint of its magnificent potential. Its kernels are encased in hard, stony shells, arranged in small, brittle ears that shatter easily, dispersing their seeds. It is a far cry from the plump, exposed kernels of modern corn, neatly aligned on a robust cob. Yet, it was this unassuming plant that indigenous farmers meticulously selected, cultivated, and ultimately transformed through generations of careful breeding – a process that remains one of the most profound acts of genetic manipulation in human history, long before the advent of modern science.

Scientists now understand that the dramatic shift from teosinte to maize involved surprisingly few genetic changes, perhaps as few as five key genes. One pivotal gene, tb1 (teosinte branched1), controls the plant’s branching pattern, dictating whether it grows into a multi-stemmed bush like teosinte or a single, robust stalk with fewer, larger ears like corn. Another, tga1, is responsible for the hardness of the kernel casing. Indigenous farmers, through keen observation and selective replanting, favored plants with softer husks and larger, more accessible kernels. This painstaking process, refined over millennia, was not an accident but a deliberate, intelligent intervention, showcasing an unparalleled understanding of plant genetics and agronomy.

From Wild Grass to Civilizational Staple

The earliest archaeological evidence of domesticated maize dates back approximately 6,250 years ago from Guila Naquitz Cave in Oaxaca, Mexico. These ancient cobs, though tiny compared to their modern descendants, are unequivocal proof of human intervention. The gradual increase in cob size over thousands of years, documented in archaeological sites across Mexico, paints a picture of continuous improvement and adaptation. This wasn’t merely about creating a food source; it was about engineering a plant capable of sustaining large, complex societies.

The genius of indigenous corn development lies not just in its initial domestication but in its subsequent diversification and adaptation. As corn spread from its Mesoamerican heartland, indigenous farmers continued to breed it for specific environments. From the arid deserts of the American Southwest to the humid lowlands of the Amazon, and the high altitudes of the Andes, corn varieties emerged, each uniquely suited to its local climate, soil, and growing season. This incredible adaptability is a testament to the decentralized yet highly effective network of indigenous plant breeders, each contributing to a vast genetic library of maize. Today, thousands of distinct landraces of corn exist, each a living archive of generations of agricultural knowledge.

More Than Food: A Sacred Connection

For the peoples of Mesoamerica, corn was far more than just sustenance; it was life itself, imbued with profound spiritual and cultural significance. The Maya, for instance, believed that humans were created from corn dough, as recounted in their sacred text, the Popol Vuh: "And thus our ancestors were formed, they who were created and formed, for they had only yellow corn and white corn for their flesh." This belief underscores the deep, almost existential connection between corn and human identity. The Aztec god Centeotl, the Inca goddess Mama Sara, and countless other deities across the Americas were associated with maize, reflecting its centrality to cosmology, rituals, and daily life.

This sacred relationship fostered a holistic approach to agriculture. Farmers understood their role not merely as cultivators but as stewards of a divine gift. This reverence translated into sustainable practices, careful seed selection, and a deep respect for the land, ensuring the continuity of the crop for future generations.

The Agricultural Revolution: A Foundation for Empires

The development of corn sparked an agricultural revolution that laid the foundation for the rise of complex civilizations. Its key advantages were manifold:

-

High Caloric Yield: Corn is a remarkably efficient energy producer. A relatively small plot of land could yield enough corn to feed a family, freeing up labor for other pursuits like craft specialization, monumental architecture, and governance. This surplus food production was critical for supporting large, dense populations and the development of urban centers like Teotihuacan, Tenochtitlan, and Machu Picchu.

-

Nutritional Powerhouse: While corn alone isn’t a complete protein, indigenous peoples developed ingenious methods to enhance its nutritional value. Nixtamalization, a process of soaking and cooking corn in an alkaline solution (typically limewater), significantly increases the bioavailability of niacin (preventing pellagra) and amino acids, while also improving its digestibility and flavor. This ancient technique, still used today to make masa for tortillas and tamales, demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of food chemistry.

-

The "Three Sisters" System: One of the most brilliant examples of indigenous agricultural innovation is the "Three Sisters" planting method, practiced by numerous North American tribes. Corn, beans, and squash are planted together in an interdependent polyculture. The corn provides a stalk for the beans to climb, keeping them off the ground. The beans, being legumes, fix nitrogen in the soil, enriching it for the corn and squash. The broad leaves of the squash plants shade the soil, suppressing weeds, retaining moisture, and deterring pests. This symbiotic relationship not only optimizes yield but also promotes soil health and biodiversity, exemplifying sustainable agriculture millennia before the term was coined.

-

Storage and Preservation: Indigenous farmers developed sophisticated techniques for storing corn, allowing for year-round food security. Corn was dried, shelled, and stored in granaries, pits, or woven containers, often treated to deter pests. This ability to store surplus harvests was crucial for surviving lean seasons and for supporting non-agricultural populations.

A Continent Transformed and a Global Legacy

From its origins in Mesoamerica, corn spread like wildfire, carried by indigenous traders and migrating communities, reaching North America by 1000 BCE and South America even earlier. Each region embraced corn, adapting it to local conditions and incorporating it into their unique culinary and cultural traditions. By the time Europeans arrived in the Americas, corn was cultivated from modern-day Canada to Chile, supporting a vast array of indigenous nations.

The arrival of Europeans marked a new chapter for corn. It was quickly recognized as a miracle crop and rapidly adopted into global agriculture. Columbus himself carried corn back to Europe, and within centuries, it had spread across Africa and Asia, becoming a staple crop for millions worldwide. Today, corn is the most widely grown grain in the world, a testament to the agricultural revolution sparked by indigenous innovators.

Enduring Legacy and Modern Relevance

In an era dominated by industrial agriculture and genetically modified organisms, the indigenous development of corn offers invaluable lessons. The thousands of landraces preserved by indigenous communities represent a vital genetic reservoir, crucial for breeding new varieties resilient to climate change, pests, and diseases. Indigenous seed savers and food sovereignty movements continue to champion the preservation of these traditional varieties, recognizing their cultural significance and their potential to feed the world sustainably.

The story of corn is not merely an ancient historical account; it is a living narrative of human ingenuity, resilience, and profound connection to the natural world. It reminds us that some of the most groundbreaking scientific and agricultural advancements were born not in laboratories, but in the fields of indigenous farmers, whose deep ecological knowledge and patient observation transformed a wild grass into the golden seed that built civilizations and continues to nourish humanity. Their legacy challenges us to look beyond conventional narratives and acknowledge the foundational contributions of indigenous peoples to our shared agricultural heritage, a revolution whose ripples are still felt across every plate, every field, and every culture touched by the magnificent maize.