The Enduring Wisdom: Traditional Preservation Methods of the Northwest Coast

The Northwest Coast of North America, a region stretching from the southern reaches of Alaska through British Columbia to northern Washington, is a land of unparalleled natural abundance. For millennia, the Indigenous peoples of this vibrant ecosystem – including the Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, Kwakwaka’wakw, Nuu-chah-nulth, Coast Salish, and many others – developed sophisticated and sustainable methods to preserve this bounty. Their ingenuity was not merely about survival; it was deeply intertwined with their spiritual beliefs, social structures, and artistic expressions. These traditional preservation methods represent a profound understanding of their environment, a testament to meticulous planning, deep reverence, and intergenerational knowledge transfer, ensuring sustenance through the lean winter months and supporting a rich ceremonial life.

Far from being mere "hunter-gatherers," the peoples of the Northwest Coast were expert resource managers and master preservers. Their sophisticated approach allowed for the accumulation of surplus, which in turn fostered complex societal structures, elaborate potlatch ceremonies, and the creation of monumental art. The core principle driving these methods was a deep respect for the land and sea, acknowledging that abundance was a gift to be carefully managed and reciprocated.

The King of Sustenance: Salmon Preservation

Central to the diet and culture of almost every Northwest Coast nation was salmon. The annual salmon runs, often occurring in multiple waves throughout the year, provided an immense, concentrated food source. The challenge was to process this perishable protein quickly and efficiently for long-term storage.

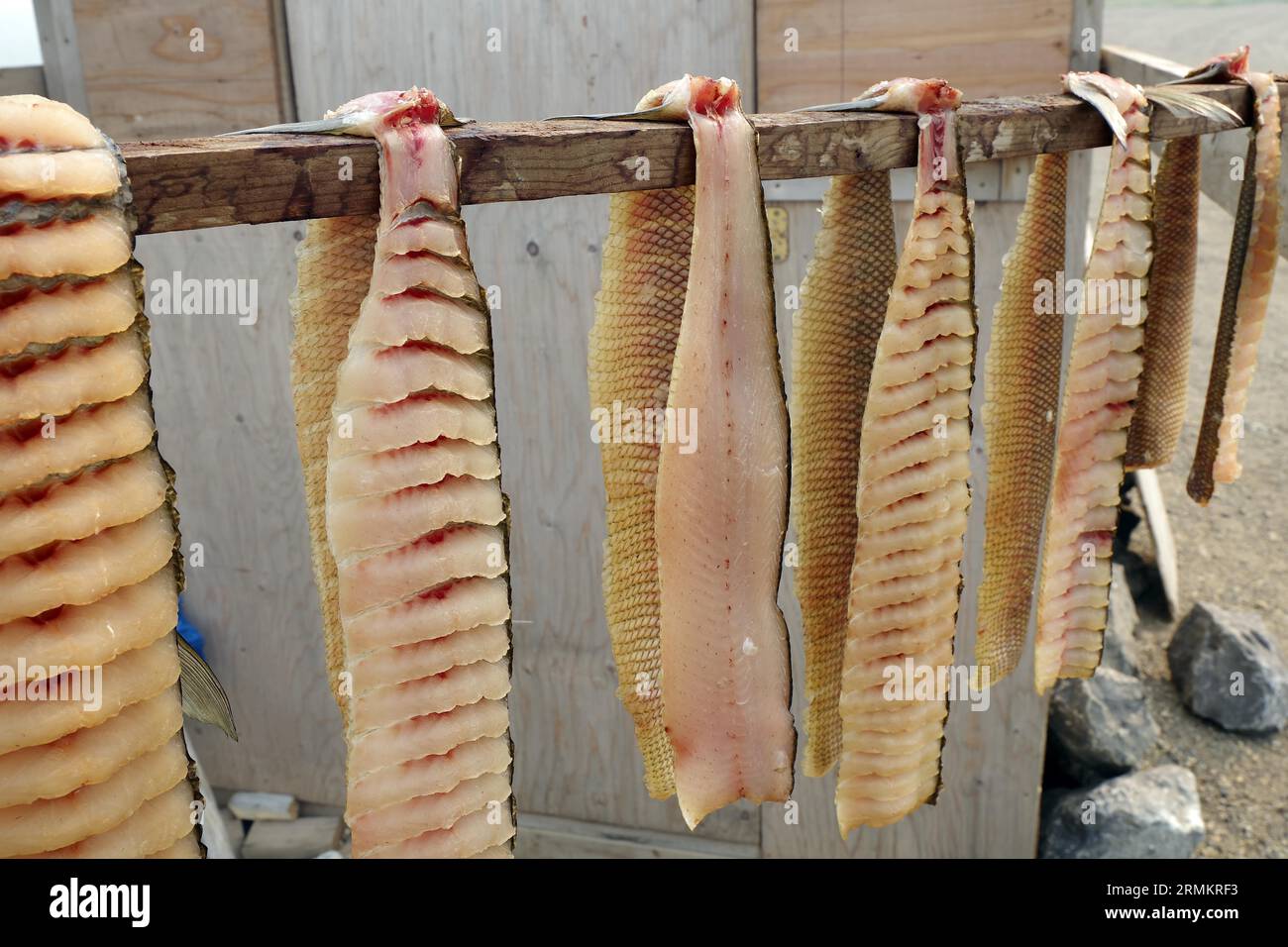

The primary method for preserving salmon was smoking and drying. As soon as the fish were caught, often in massive quantities using elaborate weirs, nets, and traps, they were swiftly brought to processing sites. Women, in particular, played a crucial role in this labor-intensive process. The salmon would be cleaned, split open, and often scored to facilitate drying. The heads, roe, and internal organs were also processed separately; roe, for instance, was dried and stored as a delicacy and nutrient-rich food.

The prepared salmon fillets were then hung on racks within large, specially constructed smokehouses. These structures were designed to allow for controlled airflow and consistent, low-heat smoke, typically from slow-burning alder or cedar wood. This process simultaneously dried the fish and infused it with compounds from the smoke, which acted as natural preservatives, inhibiting bacterial growth and rancidity. The smoking could last for days or even weeks, depending on the desired outcome and the type of fish. The result was a lightweight, nutrient-dense food source that could last for years if stored properly in cedar boxes or bark containers in cool, dry conditions. "Our ancestors knew that the salmon was our lifeblood," explained a contemporary Haida elder. "Every part of the fish was respected and used, and its preservation was a sacred task, ensuring our survival through the winter."

Beyond smoking, simple air drying was also employed, particularly in areas with consistent dry winds. Sometimes, salmon was also fermented in pits, a method that created a highly pungent, energy-rich food source, though less common for long-term storage than smoking. The sheer volume of salmon processed highlights the incredible organization and cooperative effort required within communities.

Liquid Gold: Eulachon Grease

Another critically important food source, unique to the Northwest Coast, was the eulachon (or oolichan), a small, oily fish known as the "candlefish" due to its high fat content. The eulachon runs were eagerly anticipated, as these fish provided a vital source of fat and nutrients, especially important in a diet that could otherwise be lean.

The primary preservation method for eulachon was the rendering of its oil into eulachon grease. This labor-intensive process involved allowing the fish to slightly ferment in large cedar boxes or pits for several days, breaking down the tissues. Then, the fish were boiled in large canoes or cedar boxes filled with water, and the oil was skimmed off the top. This "grease" was then cooled and solidified, becoming a highly prized commodity.

Eulachon grease was not just a food item; it was a form of currency, traded extensively along intricate "grease trails" that connected coastal communities with interior nations. It was used as a dip for dried fish and berries, a cooking medium, a medicinal balm, and even a preservative for other foods. Its value was immense; it was truly "liquid gold." A Kwakwaka’wakw proverb states, "When the eulachon runs, the people live." The careful preservation of this grease in sealed cedar boxes or woven baskets ensured a crucial fat source for the entire year.

Harvesting the Land: Berries and Other Plant Foods

While marine resources formed the cornerstone of the diet, plant foods were also vital and preserved with equal ingenuity. Various berries, such as salmonberries, blueberries, cranberries, and huckleberries, were gathered in abundance during the summer months.

The most common method for preserving berries was drying. Berries were spread out on mats or racks in the sun, or over slow fires, until they were shriveled and leathery. They were often then pressed into compact cakes or bricks, sometimes mixed with eulachon grease or other ingredients, to create nutrient-dense "berry cakes" that were easy to store and transport. These cakes would then be stored in cedar boxes, often submerged in grease or water to prevent spoilage. When rehydrated, they provided a welcome burst of flavor and vitamins during the colder months.

Roots, such as camas and fern rhizomes, were also harvested. Camas bulbs, for instance, were often pit-cooked for extended periods, a process that converted complex carbohydrates into digestible sugars, making them sweeter and easier to store. They could then be dried and stored for later consumption. Seaweed, another important marine plant, was also dried and pressed into cakes, providing essential minerals and iodine.

Preserving Materials: Wood, Bark, and Hides

Preservation methods extended far beyond food, encompassing the materials vital for shelter, transportation, tools, and ceremonial objects. The mighty Western Red Cedar (Thuja plicata) was often called the "Tree of Life" by many Northwest Coast nations, and its preservation was paramount.

Cedar wood, known for its natural resistance to rot and insects due to its inherent oils, was meticulously harvested and processed. Planks for longhouses, canoes, and bentwood boxes were carefully split from logs, seasoned, and stored in protected areas to prevent warping and decay. Cedar bark, used for weaving baskets, mats, clothing, and rain gear, was harvested in long strips without killing the tree, ensuring future harvests. The bark was then processed through retting and drying, and the natural oils in the bark provided a degree of water resistance and durability to the finished products.

Eulachon grease, beyond its culinary uses, also served as a preservative for wooden tools and carvings. Applying a thin layer of grease to wooden objects helped to seal them against moisture and prevent cracking. Similarly, animal hides, though less central than on the Plains, were tanned using traditional methods involving brain-tanning and smoking to create durable leather for clothing, bags, and drumheads.

The Preservation of Knowledge and Sustainability

Crucially, the traditional preservation methods of the Northwest Coast were not just a collection of techniques; they were an embodiment of an entire worldview. At the heart of this worldview was the concept of sustainability and reciprocity. Harvesting was governed by strict traditional laws and protocols, ensuring that resources were never overexploited. Only what was needed was taken, and gratitude was always expressed to the spirits of the land and sea. The Gitxsan term ‘Ayookw’ or ‘Ayoo’ refers to the traditional laws and customs governing resource use, emphasizing careful management and respect for all living things.

The ultimate preservation method was the intergenerational transfer of knowledge. Elders meticulously taught younger generations the intricate details of harvesting cycles, processing techniques, and storage methods. This knowledge was passed down through oral histories, songs, ceremonies, and hands-on apprenticeship. Every child grew up observing and participating in these vital activities, ensuring that the wisdom accumulated over thousands of years was not lost. The spiritual significance of these practices reinforced their importance; the act of preserving food was often accompanied by prayers and rituals of thanks.

Challenges and Revitalization

The arrival of European colonizers brought immense disruption to these traditional ways of life. Imposed fishing restrictions, land dispossession, residential schools, and the introduction of new technologies and economic systems severely impacted Indigenous peoples’ ability to practice their traditional preservation methods. Many invaluable skills and knowledge systems were suppressed or lost during this period.

However, the resilience of Northwest Coast peoples is profound. Today, there is a powerful movement to revitalize these traditional practices. Communities are reclaiming their ancestral territories, re-establishing traditional food systems, and re-learning the preservation techniques of their ancestors. Indigenous chefs are incorporating traditional preserved foods into contemporary cuisine, and cultural centers are teaching younger generations the art of smoking salmon, rendering eulachon grease, and weaving cedar bark. This revitalization is not just about food security; it’s about cultural resurgence, reconnecting with identity, and asserting sovereignty over their resources.

Conclusion

The traditional preservation methods of the Northwest Coast represent an extraordinary achievement in human adaptation and ingenuity. From the meticulous smoking of salmon to the rendering of precious eulachon grease, and the careful processing of berries and cedar, these practices ensured not just physical survival but also the flourishing of complex societies, rich artistic traditions, and vibrant spiritual lives. They were a testament to a deep ecological understanding, a sophisticated social organization, and a profound respect for the natural world. In an era increasingly concerned with food security and sustainable living, the ancient wisdom of the Northwest Coast offers invaluable lessons, reminding us that true abundance lies not just in what we gather, but in how thoughtfully we preserve and honor it. The enduring legacy of these methods continues to nourish, teach, and inspire, bridging the past with a resilient and hopeful future.