Beneath the dappled moonlight, a lone figure crouches by a sandy riverbank, headlamp illuminating the subtle churned earth. This isn’t a seasoned biologist, but Sarah, a retired teacher, meticulously documenting what she hopes are the tell-tale signs of a snapping turtle nest. Her dedication is part of a silent revolution sweeping across the vast landscapes often referred to as Turtle Island – a continent-wide network of citizen science projects, empowering ordinary people to become the frontline guardians of some of the land’s most ancient and vulnerable inhabitants: turtles.

The urgency of Sarah’s vigil, and that of thousands like her, is stark. Over 60% of the world’s freshwater turtle species are threatened with extinction, making them one of the most imperiled groups of vertebrates globally. On Turtle Island, from the Blanding’s Turtle navigating the wetlands of the Great Lakes to the Desert Tortoise enduring the arid plains of the Southwest, these keystone species face a relentless onslaught. Habitat destruction, road mortality, pollution, illegal pet trade, and climate change are pushing them to the brink. Traditional conservation efforts, while vital, often lack the sheer manpower and localized knowledge required to monitor populations scattered across immense and diverse territories. This is where citizen science steps in, transforming concern into actionable data.

The concept of "Turtle Island" itself holds profound significance, particularly for Indigenous peoples across North America, who often refer to the continent by this name, stemming from creation stories where the world was formed on the back of a giant turtle. This deep spiritual and cultural connection underscores an inherent responsibility for stewardship, a philosophy that resonates deeply with the ethos of citizen science. Many projects actively seek to integrate Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) with Western scientific methods, recognizing that Indigenous communities have observed and interacted with these species for millennia, holding invaluable insights into their behaviors, habitats, and historical population trends.

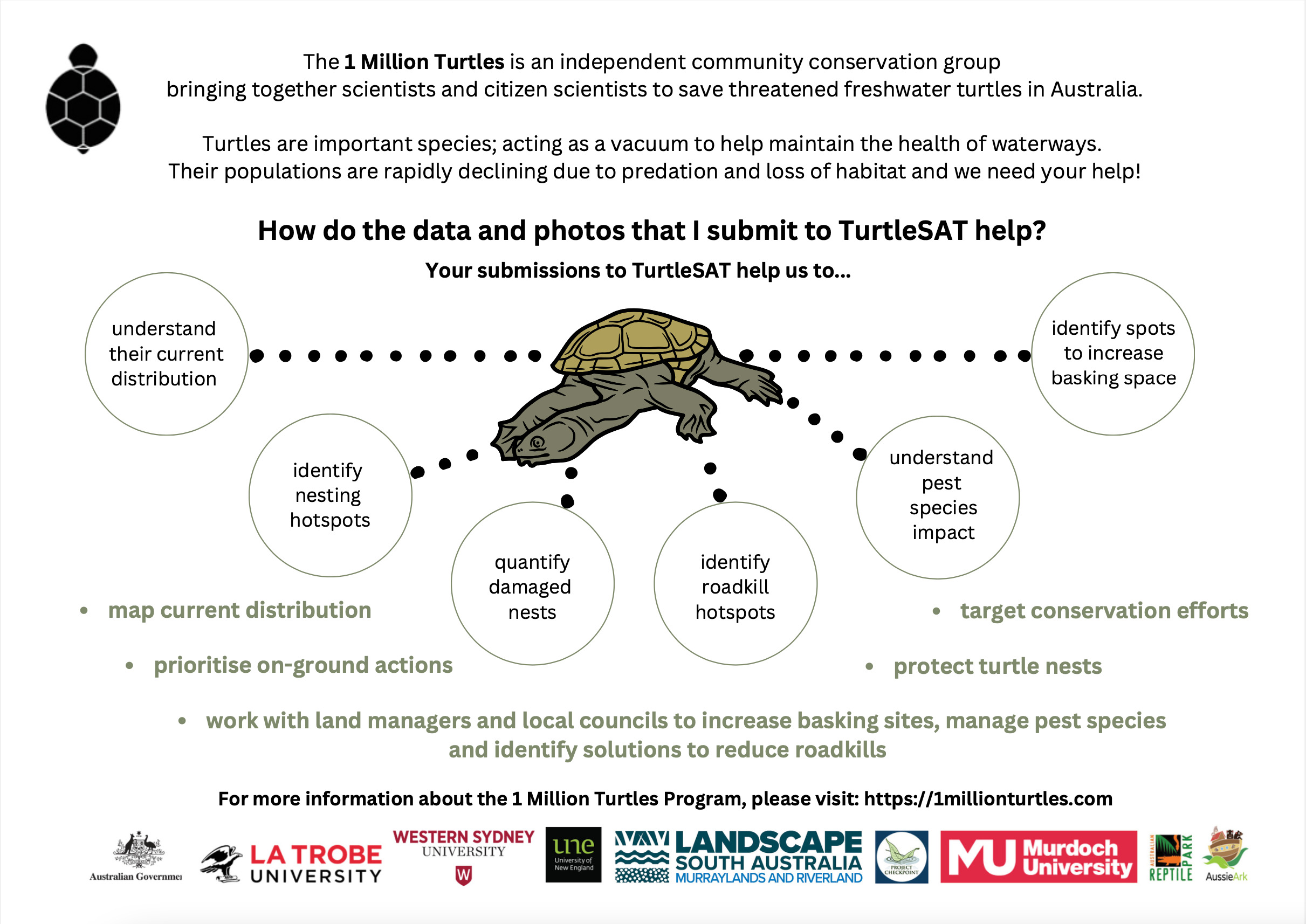

Citizen science projects for turtle monitoring are diverse, ranging from simple reporting of sightings to sophisticated data collection. One of the most common initiatives involves nest protection. Female turtles often lay their eggs in vulnerable locations, such as road shoulders, agricultural fields, or sandy areas near human habitation. These nests are highly susceptible to predation by raccoons, foxes, and skunks, as well as disturbance from human activity. Volunteers are trained to identify nesting sites, often after observing a female turtle in the act, and then to install protective cages or fences around the nest. They meticulously record the location, date, species, and number of eggs, returning later to monitor for hatchlings and ensure their safe emergence. This direct intervention has demonstrably increased hatchling success rates in many areas, providing a crucial boost to fragile populations.

Beyond nest protection, citizen scientists contribute to long-term population monitoring. Projects like "Turtle Tracker" or "Reptile Reporter" (names often vary by region and organization) empower individuals to log turtle sightings via smartphone apps or online portals. These submissions typically include the species, location (often GPS-tagged), date, and any notable observations like injuries or unusual behavior. This crowd-sourced data, when aggregated, allows researchers to identify population hotspots, migration corridors, and areas of high mortality (e.g., roadkill blackspots). Such data is invaluable for informing conservation strategies, such as the placement of ecopassages under roads, habitat restoration initiatives, or the designation of protected areas.

"Without the eyes and ears of thousands of dedicated volunteers, we’d be flying blind in many of our conservation efforts," explains Dr. Lena Petrova, a wildlife biologist specializing in chelonian conservation. "Our limited research budgets and personnel simply can’t cover the vastness of the landscapes where turtles live. Citizen scientists provide a critical layer of data density that allows us to understand population trends, identify emerging threats, and measure the effectiveness of our interventions in real-time." Her words underscore the profound impact of this decentralized approach.

Another vital aspect of citizen science is road mortality surveys. Turtles, particularly females seeking nesting sites, are highly susceptible to being struck by vehicles. Volunteers regularly patrol known turtle crossing areas, documenting deceased individuals. While grim, this data is essential for identifying dangerous road segments and advocating for solutions like warning signs, speed limit reductions during nesting seasons, or the construction of turtle fences and tunnels. The sheer volume of data collected by volunteers can provide a compelling case for infrastructure changes that would otherwise be difficult to justify without extensive, long-term monitoring.

The integration of Indigenous perspectives offers a unique strength to these projects. Elders and community members bring generations of observational knowledge about local turtle populations – where they historically nested, their seasonal movements, and changes observed over decades. This qualitative data, often passed down through oral tradition, complements the quantitative data collected by Western scientific methods. For instance, an Elder might point to a specific wetland that historically teemed with painted turtles but is now silent, prompting closer scientific investigation into the causes of decline. This collaborative approach fosters a deeper, more holistic understanding of turtle ecology and strengthens community ties to conservation efforts. "Turtles carry the wisdom of our ancestors; they are a living part of our creation story," says Elder Joseph Bear from the Anishinaabe Nation. "When we protect them, we are protecting our own history, our culture, and the health of the land itself. Citizen science is a way for all people to join in that sacred responsibility."

Despite the immense benefits, citizen science projects face challenges. Ensuring data quality and consistency across a large volunteer base requires robust training programs and user-friendly data submission platforms. Volunteer retention can also be an issue, as commitment often fluctuates. Funding for project coordination, equipment, and scientific oversight remains a constant need. Yet, the successes far outweigh these hurdles. In many regions, citizen science data has directly led to policy changes, such as new road safety measures, expanded protected areas, and increased public awareness campaigns. It has also fostered a new generation of environmental stewards, connecting people directly with nature and cultivating a profound sense of ownership over local conservation issues.

The future of turtle monitoring on Turtle Island increasingly hinges on this collaborative model. As climate change alters habitats and human pressures continue to intensify, the need for widespread, grassroots monitoring will only grow. Projects are evolving to incorporate more advanced technologies, such as AI-powered image recognition for species identification or acoustic monitoring for detecting rare species. Crucially, the continued emphasis on integrating Indigenous knowledge and fostering community leadership will ensure that these efforts are not just scientifically sound but also culturally resonant and sustainable in the long term.

Sarah, the retired teacher, eventually finds her turtle nest. It’s a Blanding’s Turtle, a species of special concern, identified by its distinctive yellow chin. She carefully places a protective cage, records the GPS coordinates, and takes a moment to appreciate the quiet miracle unfolding beneath the moon. It’s a small act, multiplied by thousands of similar acts across Turtle Island every night, every season. These citizen scientists are not just collecting data; they are weaving a tapestry of shared responsibility and hope, ensuring that the ancient, resilient spirit of the turtle continues to thrive on the land that bears its name, for generations to come. Their dedication underscores a fundamental truth: the fate of these venerable reptiles, and indeed, the health of our shared planet, rests in the collective hands of its inhabitants.