The Unfulfilled Promise: UNDRIP and the Struggle for Indigenous Rights on Turtle Island

Turtle Island, a name resonant with Indigenous heritage and deep historical memory for the land now commonly known as North America, remains a contested space where the aspirations of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) frequently collide with the entrenched realities of colonial legacy and ongoing systemic injustices. Adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2007, UNDRIP is a landmark international instrument affirming the collective and individual rights of Indigenous peoples, serving as a universal framework for their survival, dignity, and well-being. Yet, on Turtle Island, its principles often exist in a precarious state, lauded in rhetoric but frequently undermined in practice, exposing a profound gap between international commitment and domestic implementation.

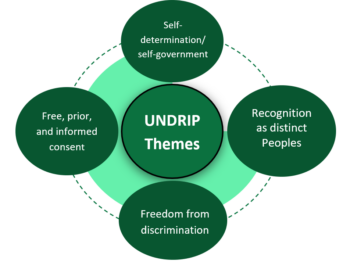

The very genesis of UNDRIP is rooted in a global recognition of the historical injustices suffered by Indigenous peoples, including those on Turtle Island, who have endured dispossession, assimilation, and discrimination. Its 46 articles outline a comprehensive set of rights, ranging from self-determination and land rights to cultural preservation and the right to free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC). For the diverse Indigenous nations of Turtle Island – including First Nations, Inuit, Métis in Canada, and numerous Tribal Nations in the United States – UNDRIP offers a powerful tool to assert inherent rights and hold settler governments accountable. However, the path from declaration to lived reality is fraught with challenges, legal complexities, and a persistent lack of political will.

Self-Determination: The Bedrock of Sovereignty

Article 3 of UNDRIP unequivocally states, "Indigenous peoples have the right to self-determination. By virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development." This is arguably the most fundamental principle, directly challenging centuries of colonial policies designed to dismantle Indigenous governance structures. On Turtle Island, this right has been systematically denied through instruments like the Indian Act in Canada, which imposed a foreign governance system, and various US federal policies that sought to terminate tribal sovereignty.

Today, while both Canada and the United States have officially endorsed UNDRIP (after initially voting against it), the practical application of self-determination remains contested. Many Indigenous nations are actively rebuilding their governance, legal, and educational systems, often against significant financial and political odds. The Nisga’a Nation in British Columbia, for instance, secured a modern treaty in 2000 that recognizes their self-government and land ownership, predating Canada’s official endorsement of UNDRIP but embodying its spirit. Similarly, numerous Tribal Nations in the US operate sophisticated judicial systems and engage in nation-building initiatives. Yet, these examples are often hard-won and not uniformly applied. Governments frequently retain ultimate authority, particularly over resource development, demonstrating a reluctance to fully cede control to Indigenous nations, thereby limiting their ability to truly "freely determine their political status."

Land, Territories, and Resources: The Epicenter of Conflict

Perhaps nowhere is the tension between UNDRIP’s principles and Turtle Island’s reality more acute than in the realm of land, territories, and resources. Articles 26, 28, and 32 are particularly relevant, asserting Indigenous peoples’ rights to their traditional lands, territories, and resources, and the crucial principle of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) for any projects affecting them. FPIC demands that Indigenous peoples have the right to withhold consent, going far beyond mere consultation.

On Turtle Island, the historical dispossession of Indigenous lands forms the bedrock of settler states. Treaties, often signed under duress or subsequently violated, govern much of the land, yet their interpretation and enforcement remain a constant source of dispute. Contemporary conflicts over resource extraction – pipelines, mines, logging – frequently pit Indigenous land defenders against government and corporate interests. The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s struggle against the Dakota Access Pipeline in the US, or the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs’ opposition to the Coastal GasLink pipeline in Canada, are stark illustrations.

In these cases, governments often invoke a "duty to consult," a legal concept that falls short of FPIC. Critics argue that this duty is frequently treated as a checkbox exercise, aimed at mitigating risk rather than genuinely seeking and respecting Indigenous consent. The result is often forced industrial development on or near Indigenous territories, leading to environmental degradation, cultural disruption, and the criminalization of Indigenous land defenders. The argument that such projects are "in the national interest" often overshadows and discredits Indigenous rights, demonstrating a clear failure to uphold UNDRIP’s core principles regarding land and resources.

Cultural Rights, Language, and Education: Reclaiming Identity

UNDRIP also enshrines vital cultural rights, including the right to revitalize, use, and develop Indigenous languages (Article 13), and to establish and control their educational systems (Article 14). For Indigenous peoples on Turtle Island, these rights are deeply intertwined with the devastating legacy of residential schools in Canada and boarding schools in the US. These institutions, often run by churches and funded by governments, were explicitly designed to "kill the Indian in the child," forcibly assimilating generations of Indigenous youth and systematically eradicating their languages, cultures, and spiritual practices. The findings of Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) report, which detailed the horrific abuses and intergenerational trauma caused by residential schools, underscore the urgent need for cultural revitalization.

Today, Indigenous communities across Turtle Island are engaged in heroic efforts to reclaim what was lost. Language immersion schools, cultural revitalization programs, and the creation of Indigenous-led curricula are powerful acts of self-determination and healing. The success of programs like the Immerse Yourself project in Hawaii (which, while not strictly Turtle Island, offers a poignant parallel) in revitalizing the Hawaiian language, demonstrates what is possible with dedicated community effort and some government support. However, these initiatives often face chronic underfunding and a lack of sustained commitment from settler governments. The right to control their own educational institutions, free from external interference, is crucial for fostering cultural resilience and ensuring that Indigenous youth learn their histories, languages, and worldviews.

Justice, Redress, and Reconciliation: A Long Road Ahead

Articles 28 and 29 of UNDRIP speak to the right to redress for historical injustices, including lands and resources taken without consent, and the right to maintain and strengthen their distinct relationship with their lands. Reconciliation, as articulated by the TRC in Canada, involves a commitment to repair past harms and build a new relationship based on mutual respect. UNDRIP provides a framework for this, demanding recognition of historical injustices and a commitment to address their ongoing impacts.

While Canada has embarked on a reconciliation journey, including the passage of the UNDRIP Act in 2021, which commits the federal government to align its laws with the declaration, progress is slow and uneven. Many of the TRC’s 94 Calls to Action remain unfulfilled, and the systemic issues that perpetuate disparities persist. In the US, a formal national reconciliation process akin to Canada’s TRC has not materialized, though individual tribal nations and some states are pursuing their own paths to healing and justice.

The crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-Spirit People (MMIWG2S) across Turtle Island serves as a grim indicator of the continuing systemic discrimination and violence faced by Indigenous communities. This crisis is a direct consequence of colonialism, marginalization, and the failure of state institutions to protect Indigenous lives, underscoring the urgent need for justice and systemic change that aligns with UNDRIP’s principles of non-discrimination and protection of vulnerable groups.

Challenges and the Path Forward

The primary challenge to UNDRIP’s full implementation on Turtle Island is its legal status. While an international human rights instrument, it is generally considered non-binding in the same way a treaty is. Its strength lies in its moral and political authority, setting a minimum standard for the treatment of Indigenous peoples. However, without robust domestic legal frameworks and the genuine political will to uphold it, its principles can be easily sidestepped. Both Canada and the US have domestic legal systems that often prioritize existing property rights, resource development, and state sovereignty over Indigenous inherent rights, leading to protracted legal battles where Indigenous nations are forced to fight for what UNDRIP already affirms.

Despite these immense hurdles, UNDRIP remains a powerful catalyst for change. It empowers Indigenous peoples, provides a common language for advocacy, and serves as a benchmark against which government actions can be measured. Indigenous-led initiatives, backed by international solidarity and legal challenges, continue to push the boundaries of what is possible. The increasing recognition of Indigenous legal orders, the growing number of modern treaties, and the tireless work of grassroots activists offer glimpses of a future where UNDRIP’s promise might finally be realized.

Ultimately, the application of UNDRIP principles to Turtle Island is not merely a legal exercise; it is a moral imperative. It demands a fundamental shift in the relationship between Indigenous peoples and settler states – from one of dominance and assimilation to one of respect, recognition, and partnership. Only through genuine commitment to self-determination, the protection of lands and cultures, and true redress for past harms can Turtle Island move closer to a future where the rights of all its original peoples are not just declared, but truly lived. The journey is long, but the Declaration provides the map.