Echoes of the Land: Unveiling Turtle Island and the Indigenous Toponymy of the Pacific Northwest

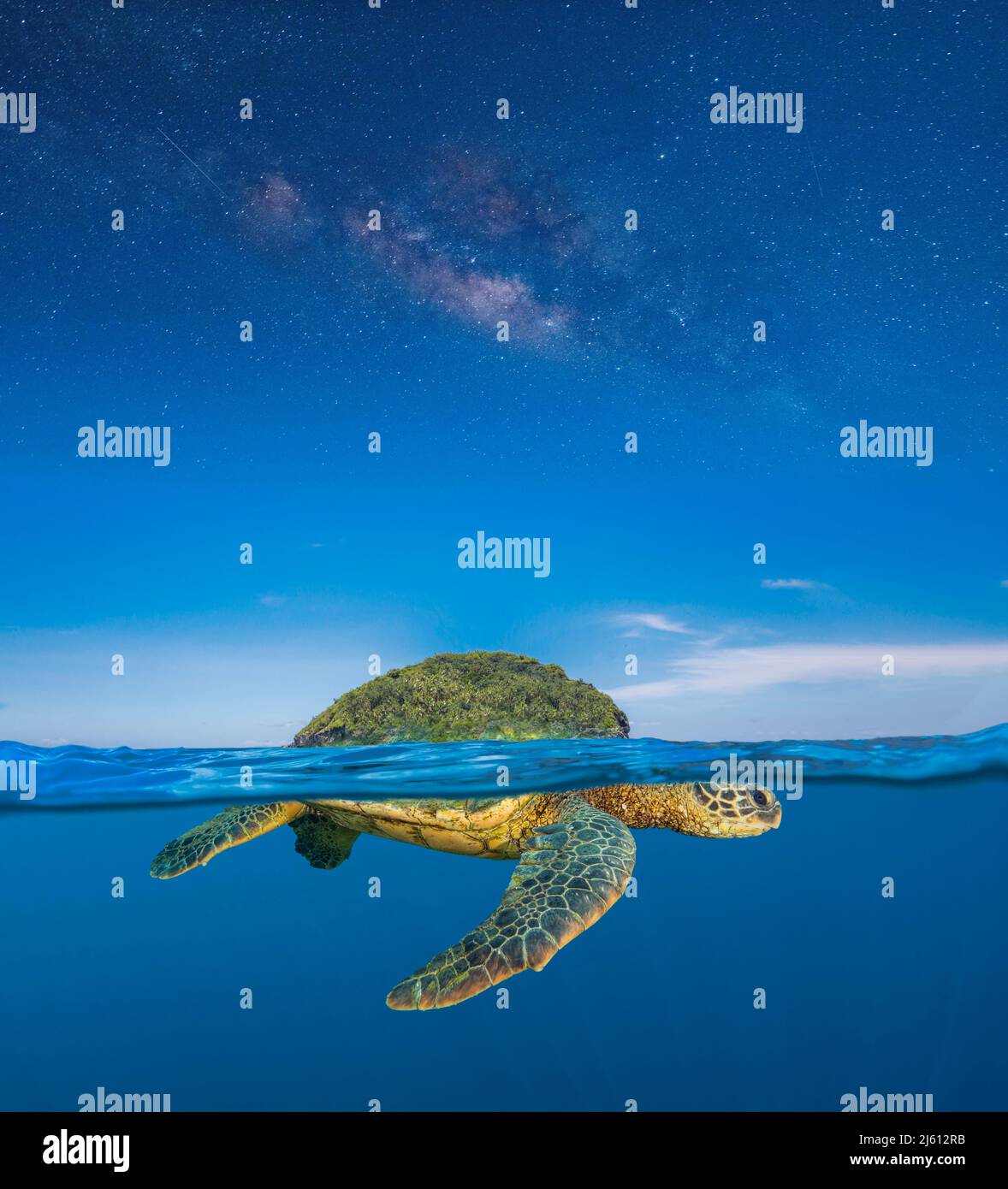

The landscape of North America, commonly known by its colonial appellation, holds a far older and more profound name within Indigenous cosmologies: Turtle Island. This foundational concept, originating from the creation stories of various First Nations, particularly the Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee, speaks not just of a landmass but of an interconnected world, born from water and sustained by the resilience of a turtle’s back. It is a name imbued with deep spiritual, cultural, and ecological significance, representing a worldview where humanity is part of a reciprocal relationship with the earth, rather than its master.

Turtle Island is more than a geographical descriptor; it is a living metaphor for the continent and its peoples, a testament to enduring presence and profound wisdom. The creation narratives typically recount a great flood, from which a muskrat or another animal brings a handful of earth to be placed upon a giant turtle’s back, which then grows into the land we know. This narrative underscores themes of collaboration, humility, and the sacred origins of the earth, contrasting sharply with the often transactional relationship fostered by colonial perspectives. Recognizing Turtle Island is an act of acknowledging a continent’s true history, its original inhabitants, and a spiritual framework that continues to inform Indigenous stewardship.

While Turtle Island offers a continental lens, a similar depth of meaning is found in the specific place names across its vast expanse. Nowhere is this more evident than in the Pacific Northwest, a region of unparalleled natural beauty and immense linguistic and cultural diversity. Here, the mountains, rivers, islands, and coastlines bear names that are not arbitrary labels but intricate maps of history, ecology, and human experience, passed down through millennia. These Indigenous toponyms – the names given to places – are living archives, encoding knowledge about resources, travel routes, spiritual sites, historical events, and the very character of the land and its waters.

The Pacific Northwest, stretching from the temperate rainforests of British Columbia and Southeast Alaska down through Washington and Oregon, is home to hundreds of distinct Indigenous nations. Their languages, often belonging to large families like Salishan, Wakashan, Tsimshianic, and Athabaskan, are intimately tied to their territories. The act of learning and speaking these original place names is a powerful step towards decolonization, acknowledging the continuous presence and sovereignty of Indigenous peoples.

Consider the Salish Sea, a body of water that encompasses Puget Sound, the Strait of Georgia, and the Strait of Juan de Fuca. For centuries, various Coast Salish peoples have navigated and lived along its shores. The term "Salish Sea" itself is a modern reclamation, officially recognized in 2010, that acknowledges the shared heritage of the Indigenous peoples whose cultures and languages are intertwined with these waters. Before this recognition, the various components of the Salish Sea bore colonial names, fragmenting a naturally unified ecological and cultural system. The Coast Salish names for these waters and the land around them are far more descriptive and reflective of their deep connection. For example, Whulge (pronounced HWALG), a Lushootseed word, refers to the larger Puget Sound area, meaning "saltwater."

In what is now Seattle, Washington, the original inhabitants are the Duwamish people, whose name in Lushootseed is dxʷdəwʔabš (pronounced dxw-duh-wobsh), meaning "people of the inside." The city itself takes its name from Chief Seattle (siʔaɫ), a leader of the Suquamish and Duwamish tribes. His profound speech, often paraphrased, encapsulates the Indigenous relationship with the land: "Every part of this soil is sacred in the estimation of my people. Every hillside, every valley, every plain and grove, has been hallowed by some sad or happy event in days long vanished." This sentiment echoes the foundational principles of Turtle Island, where land is not property but kin.

Further north, in what is now British Columbia, the city of Vancouver sits on the unceded traditional territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations. Stanley Park, a beloved urban greenspace, was once Xwayxway (pronounced kway-kway) to the Squamish, a significant village site and cultural hub. The name change erases centuries of history and a vibrant community. The Musqueam name for their territory is xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (pronounced hw-muhth-kwee-um), which refers to the grass that grows along the Fraser River delta. Each of these names is a narrative, a map, a history lesson embedded in sound.

The mountains, too, hold ancient names that tell stories. Mount Rainier, a prominent feature in the Washington landscape, is known as Tahoma or Tacoma in various Salish languages, often interpreted as "mother of waters" or "great white mountain." This name speaks to its role as the source of numerous rivers, vital for the ecosystems and peoples below. Similarly, Mount Hood in Oregon is Wy’east to the Multnomah people, one of the many Indigenous groups whose ancestral lands surround the peak. These names are not merely identifiers but expressions of reverence and understanding of geological and hydrological significance.

The act of colonial renaming was a deliberate strategy to assert dominance and erase Indigenous presence. By replacing ancient, meaningful names with European ones – often those of explorers, monarchs, or distant towns – colonizers sought to disconnect Indigenous peoples from their territories and diminish their deep-seated knowledge. This linguistic colonization was a form of cultural violence, severing the continuity of oral traditions and place-based identities.

However, the tide is turning. Across the Pacific Northwest, there is a growing movement to reclaim and revitalize Indigenous place names. This effort is led by Indigenous communities themselves, often in partnership with academics, linguists, and local governments. Language revitalization programs are crucial, as the survival of these names is intimately linked to the survival of the languages they originate from. When a language is lost, an entire worldview, including its intricate system of toponymy, is also at risk.

For example, the ʔəliʔ (pronounced ah-leeth) or "salmon" in Lushootseed, is not just a fish; it is a cultural cornerstone, a provider, a spiritual entity. The names of rivers and fishing sites often reflect this deep relationship, encoding information about salmon runs, spawning grounds, and sustainable harvesting practices. Losing these names means losing a critical component of ecological knowledge and cultural identity.

Land acknowledgements, now increasingly common at public events and institutions, are a first step in this process. While they can sometimes be performative, their true purpose is to prompt reflection on whose ancestral lands one stands upon, and to recognize the enduring presence and rights of Indigenous peoples. A meaningful land acknowledgement should lead to further learning, action, and support for Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination. It is a moment to connect the local reality of a place with the broader understanding of Turtle Island.

The concept of Turtle Island and the specific Indigenous place names of the Pacific Northwest converge on a singular, powerful message: the land is alive, sacred, and holds the memory of generations. It is a reminder that the stories of this continent are far older and more complex than those found in colonial history books. The act of speaking an Indigenous place name, or understanding the significance of Turtle Island, is an act of respect, a challenge to dominant narratives, and an invitation to see the world through a lens of profound connection and stewardship.

As we navigate the complexities of environmental crises and social justice, the wisdom embedded in Indigenous toponymy and the concept of Turtle Island offers vital guidance. It calls us to move beyond mere ownership of land to a deeper relationship of reciprocity and care. It reminds us that our collective future depends on listening to the echoes of the land, learning from those who have stewarded it since time immemorial, and honoring the names that tell its true story. The journey to truly inhabit Turtle Island begins with understanding its name and the myriad names that form the fabric of its diverse and vibrant regions, particularly the breathtaking and culturally rich Pacific Northwest.