Unceded Ground: The Enduring Battle for Indigenous Land Rights on Turtle Island

On Turtle Island, the vast continent known today as North America, an ancient struggle for land, sovereignty, and self-determination persists with unwavering intensity. For Indigenous peoples, land is not merely property; it is the bedrock of identity, culture, spirituality, and survival. It is the source of laws, languages, and traditional knowledge. The fight for Indigenous land rights activism on Turtle Island is a complex, multifaceted movement rooted in centuries of colonial dispossession, broken treaties, and systemic oppression, yet it is simultaneously a vibrant assertion of resilience, inherent title, and a profound vision for a sustainable future.

The history of Turtle Island is inextricably linked to the theft of Indigenous lands. European colonizers arrived with doctrines like terra nullius (land belonging to no one) and the Doctrine of Discovery, asserting dominion over territories already inhabited by sovereign nations. Treaties, often signed under duress or misunderstood due to linguistic and cultural differences, were routinely violated, leading to forced removals, the Indian Removal Act, and the establishment of reserves and reservations – tiny fragments of ancestral lands. This historical trauma continues to ripple through contemporary Indigenous communities, manifesting as intergenerational poverty, cultural erosion, and a profound sense of injustice.

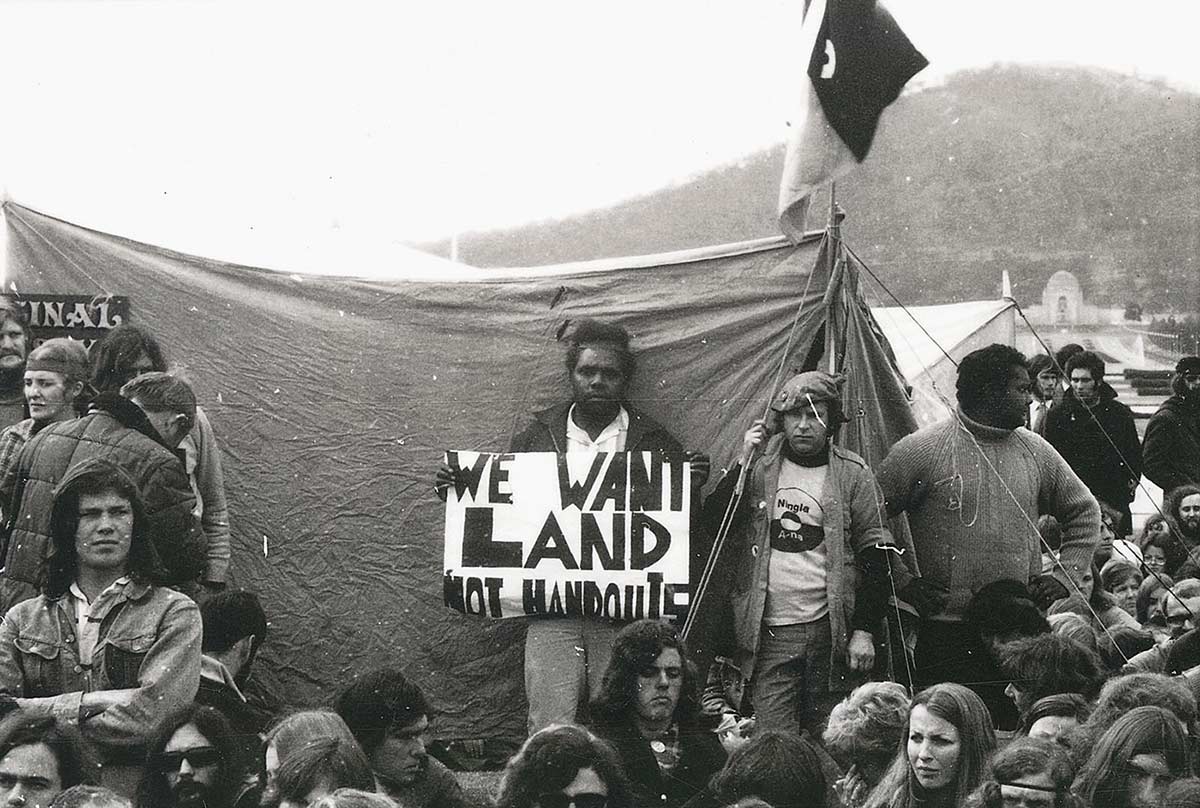

Today, the battleground for land rights is diverse, ranging from remote wilderness to bustling urban centers, but the core demand remains consistent: recognition and restitution of Indigenous title and rights. Activism takes myriad forms, from direct action and blockades to legal challenges, international advocacy, and the burgeoning "Land Back" movement. These efforts are not simply about reclaiming parcels of land; they are about restoring Indigenous governance, revitalizing traditional economies, protecting sacred sites, and asserting the inherent right to self-determination that pre-dates and supersedes colonial law.

One of the most visible and impactful fronts of this activism is the resistance to resource extraction projects. Pipelines, mines, logging operations, and hydroelectric dams frequently encroach upon unceded Indigenous territories or lands protected by treaties, threatening pristine ecosystems, sacred sites, and traditional ways of life. The slogan "Water is Life" (Mni Wiconi in Lakota) became a global rallying cry during the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s struggle against the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) in 2016-2017. This grassroots movement, which saw thousands of Water Protectors from hundreds of Indigenous nations and allies converge in North Dakota, brought unprecedented international attention to Indigenous land rights and environmental justice. While the pipeline ultimately became operational, Standing Rock demonstrated the power of collective Indigenous resistance and highlighted the deep spiritual connection Indigenous peoples have to their lands and waters. As Chairman Dave Archambault II of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe stated during the DAPL protests, "We are not fighting just for us. We are fighting for everyone."

Similarly, the Wet’suwet’en Nation in British Columbia, Canada, has been at the forefront of resisting the Coastal GasLink (CGL) pipeline project since 2019. This conflict starkly illustrates the clash between Indigenous customary law and colonial legal frameworks. The Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs, who hold authority over their traditional territories under their ancient governance system, have consistently opposed the pipeline, asserting that the company does not have their free, prior, and informed consent. Despite a landmark 1997 Supreme Court of Canada ruling (Delgamuukw v. British Columbia) that affirmed Aboriginal title and rights to their unceded territories, the Canadian and provincial governments have continued to authorize the pipeline, leading to repeated police enforcement against Wet’suwet’en land defenders and their supporters. This ongoing struggle underscores that legal victories often require continued direct action to be enforced, and that the assertion of inherent Indigenous jurisdiction often directly conflicts with state and corporate interests.

The "Land Back" movement represents a more comprehensive and visionary approach to Indigenous land rights. It’s not merely about returning specific parcels of land but about a paradigm shift—a decolonial project aimed at dismantling the structures that perpetuate Indigenous dispossession and restoring Indigenous sovereignty over their traditional territories. This includes advocating for the return of national parks and public lands, the re-establishment of Indigenous-led conservation efforts, and the transfer of decision-making power back to Indigenous communities. For instance, the Shinnecock Indian Nation on Long Island, New York, has been actively campaigning for the return of ancestral lands for decades, particularly for economic development that aligns with their cultural values, challenging the encroaching development of one of the wealthiest regions in the United States. The Land Back movement recognizes that environmental crises, social inequities, and climate change are inextricably linked to colonial land practices and that Indigenous knowledge and governance offer vital pathways to healing both the land and society.

Beyond direct action and broad movements, Indigenous land rights activism also engages with legal and political systems, albeit often with frustration. Indigenous nations frequently launch court cases to assert treaty rights, challenge government decisions, or seek recognition of unceded title. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), adopted in 2007, provides a crucial international framework affirming Indigenous peoples’ rights to their lands, territories, and resources, including the right to free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) before any development project affecting their lands. While both Canada and the United States have endorsed UNDRIP, its implementation remains a significant challenge, often requiring sustained advocacy and pressure from Indigenous communities to translate its principles into concrete policy and practice.

However, activism for land rights is not without immense challenges and dangers. Indigenous land defenders disproportionately face criminalization, harassment, and violence. Reports from organizations like Front Line Defenders and Global Witness consistently highlight that Indigenous activists are among the most vulnerable to attacks globally, especially those defending land and environmental rights. In Canada, the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) found a direct link between resource extraction projects and increased violence against Indigenous women and girls in "man camps" associated with these developments. The systemic racism embedded within policing and justice systems often means that Indigenous protesters are treated as criminals, while corporate interests are protected.

Despite these formidable obstacles, the impact of Indigenous land rights activism is undeniable. It has fundamentally shifted public discourse around environmental protection, climate change, and human rights. Indigenous peoples, often described as the original environmentalists, are increasingly recognized as crucial voices in the global fight against climate change, offering traditional ecological knowledge and stewardship practices that contrast sharply with extractive capitalist models. Their resistance has led to policy changes, forced corporations to reconsider projects, and inspired broader social justice movements. It has also fostered a profound cultural resurgence within Indigenous communities, strengthening connections to language, ceremonies, and traditional governance systems.

The ongoing struggle for Indigenous land rights on Turtle Island is a testament to the enduring spirit and resilience of Indigenous peoples. It is a demand for justice, not charity; for sovereignty, not mere consultation. It is a call to honor treaties, respect inherent rights, and acknowledge that the health of the land is intrinsically tied to the well-being of its original caretakers. As the world grapples with escalating environmental crises and the urgent need for sustainable practices, the lessons and leadership emerging from Indigenous land rights activism offer a critical path forward. The path to true justice on Turtle Island lies not in symbolic gestures, but in substantive action: the return of land, the respect of inherent rights, and the recognition of Indigenous self-determination as the cornerstone of a truly equitable future. The ground remains unceded, and the fight for its rightful return continues with unwavering determination.