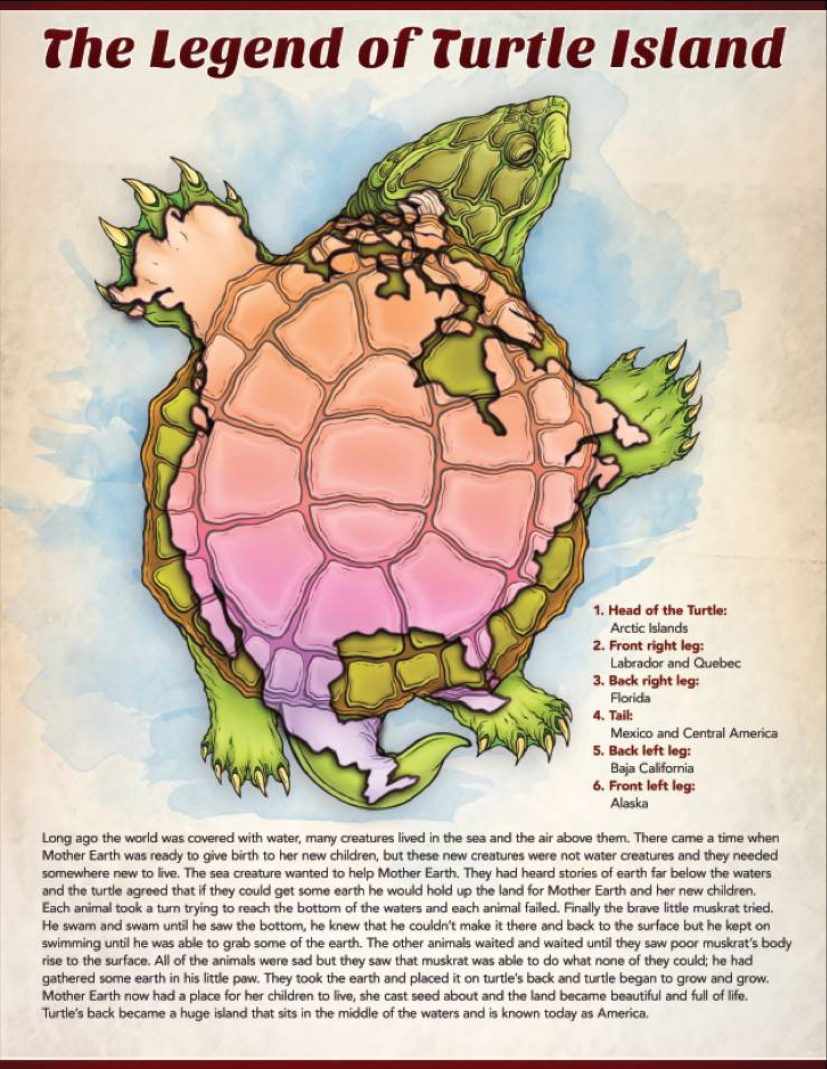

Reclaiming the Narrative: Ethical Research with Indigenous Peoples on Turtle Island

For centuries, research conducted on Indigenous peoples across Turtle Island – the ancestral lands now known as North America – has been a deeply fraught endeavor, often characterized by extraction, exploitation, and a profound disregard for Indigenous sovereignty and well-being. From anthropological studies that pathologized cultures to medical experiments that ignored consent, the history is scarred by practices that served colonial agendas rather than Indigenous communities. Today, a critical paradigm shift is underway, moving from research on Indigenous peoples to research with and by them, guided by principles of respect, reciprocity, and self-determination. This evolution is not merely about refining research methods; it is a fundamental act of decolonization, aiming to heal historical wounds and build equitable futures.

The legacy of unethical research casts a long shadow. Early anthropological and ethnographic studies frequently portrayed Indigenous cultures as "primitive" or "vanishing," contributing to harmful stereotypes and justifying assimilation policies. Researchers often extracted knowledge, artifacts, and even human remains without consent, appropriating intellectual property and spiritual items. Medical research, too, has a dark past, including forced sterilizations of Indigenous women, particularly in the mid-20th century, and the unethical collection of genetic material, such as the controversies surrounding the Human Genome Diversity Project where Indigenous communities felt their sacred biological essence was being commodified. Perhaps the most devastating example of institutional "research" was the residential school system in both Canada and the United States, which, under the guise of education and assimilation, subjected generations of Indigenous children to horrific abuse, cultural genocide, and medical experimentation, leaving an indelible scar on families and communities. These historical traumas have fostered a deep, justifiable mistrust of external researchers and institutions.

The shift towards ethical research is fundamentally about addressing this historical injustice and empowering Indigenous communities to control their own narratives and futures. At its core, this movement champions the principle of Indigenous data sovereignty, asserting that Indigenous nations have the right to own, control, access, and possess information about their peoples, lands, and cultures.

One of the most significant and widely adopted frameworks for ethical research with First Nations in Canada, and increasingly influencing Indigenous research globally, is OCAP® – Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession. Developed by the First Nations Information Governance Centre (FNIGC), OCAP® is more than just a set of ethical guidelines; it is a declaration of inherent rights.

- Ownership: Refers to the relationship between a First Nation and its information. A First Nation owns the information collectively, just as an individual owns their personal information.

- Control: Affirms that First Nations control all aspects of research and information management processes that impact them. This includes design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, and dissemination.

- Access: Refers to the right of First Nations to access information and data about themselves and their communities, regardless of where it is held. It also dictates who else can access this information and under what conditions.

- Possession: Relates to the physical control of data. First Nations have the right to physically possess data pertaining to their communities, ensuring its security and cultural relevance.

OCAP® fundamentally reorients the power dynamic in research, moving it from the researcher to the community. It recognizes that data is not merely information but a vital resource that impacts self-determination, governance, and well-being.

Complementing OCAP® is the broader principle of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC), enshrined in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). FPIC mandates that Indigenous peoples must give their consent before any project or research affecting their lands, territories, or resources can proceed.

- Free: Consent must be given voluntarily, without coercion, manipulation, or intimidation.

- Prior: Consent must be sought sufficiently in advance of any activity, allowing communities ample time to understand, discuss, and decide.

- Informed: Communities must be provided with all relevant information about the proposed research, including its purpose, methodology, potential risks and benefits, scope, duration, and data management plans, in a culturally appropriate and accessible manner.

FPIC moves beyond mere consultation, granting Indigenous peoples the right to say "no" and ensuring their active participation in decision-making processes. Article 31 of UNDRIP further strengthens these rights, stating that Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain, control, protect, and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions, as well as the manifestations of their sciences, technologies, and cultures. This article directly impacts how research on traditional ecological knowledge, languages, and cultural practices must be conducted – with Indigenous oversight and benefit.

Beyond these foundational principles, ethical research with Indigenous peoples on Turtle Island emphasizes several key practices:

- Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR): This collaborative approach actively involves community members in all stages of the research process, from identifying research questions to disseminating findings. It ensures that research is relevant, culturally appropriate, and directly addresses community priorities.

- Reciprocity and Mutual Benefit: Ethical research is not a one-way extraction of information. It requires a commitment to giving back to the community in meaningful ways, whether through capacity building, direct benefits, shared resources, or findings that directly inform policy and practice for community improvement. Researchers must ask: "How will this research benefit the community?"

- Relationship Building: Trust is paramount. This often means investing significant time in building genuine, respectful relationships with community leaders, Elders, and members, sometimes long before any formal research proposal is even considered. This is a long-term commitment, not a transactional one.

- Cultural Humility and Competency: Researchers must approach their work with humility, acknowledging their own biases and limitations, and a genuine willingness to learn from Indigenous knowledge systems and protocols. This includes understanding local customs, languages, and governance structures.

- Indigenous Leadership and Co-Creation: The ideal is Indigenous-led research, where Indigenous scholars and community members drive the research agenda. When external researchers are involved, it should be in a co-creative capacity, with Indigenous partners holding significant decision-making power.

- Respect for Traditional Knowledge: Recognizing Indigenous knowledge systems as valid, sophisticated, and essential forms of knowledge, distinct from but equally valuable as Western scientific paradigms. This involves respecting intellectual property rights and traditional protocols around knowledge sharing.

- Ethical Data Management and Dissemination: Ensuring that data is stored securely, in accordance with community wishes (often on community servers or with Indigenous organizations), and that research findings are disseminated in accessible and culturally appropriate formats, beyond just academic journals.

Despite the growing awareness and commitment to these principles, challenges persist. Academic institutions often operate within structures that privilege Western knowledge, fast-paced publication, and individual authorship, which can conflict with the slower, relational, and collective nature of Indigenous research protocols. Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), while crucial for human subjects protection, often lack the specific cultural competency required to adequately review Indigenous research proposals, sometimes inadvertently perpetuating colonial oversight. Funding mechanisms can also be restrictive, favoring short-term projects over the long-term relationship building essential for ethical Indigenous research.

Yet, the impact of truly ethical, Indigenous-led, and community-driven research is transformative. It contributes to the revitalization of Indigenous languages and cultures, supports community healing from intergenerational trauma, strengthens self-governance and nation-building, and provides culturally relevant solutions to pressing issues like health disparities, environmental degradation, and economic development. For example, research co-created with Inuit communities in the Canadian Arctic has led to culturally appropriate mental health interventions, addressing unique challenges like climate change impacts and historical injustices. Similarly, First Nations-led studies on traditional land use are instrumental in asserting land rights and informing conservation efforts, demonstrating the power of Indigenous knowledge in contemporary contexts.

As numerous Indigenous scholars and leaders have articulated, true ethical research is fundamentally about self-determination – the right of Indigenous peoples to govern themselves and control their own futures. It is an ongoing journey, requiring continuous learning, adaptation, and a profound commitment to justice. For researchers on Turtle Island, moving forward means not only adhering to ethical guidelines but embodying a spirit of partnership, humility, and genuine respect for the inherent sovereignty and wisdom of Indigenous nations. Only through such committed action can research truly contribute to reconciliation, healing, and the flourishing of all peoples on these ancient lands. The future of research on Turtle Island depends on it.