Reclaiming the Muck: The Urgent Mission to Restore Bog Turtle Habitats Across Turtle Island

The bog turtle ( Glyptemys muhlenbergii ), North America’s smallest turtle, is a creature of humble proportions but immense ecological significance. Averaging a mere three to four inches in length, its distinctive orange or yellow patch on either side of its head belies a precarious existence. This diminutive reptile, once a quiet inhabitant of the eastern United States, now stands as a critical indicator of wetland health, its future inextricably linked to the success of ambitious habitat restoration efforts spanning what many Indigenous peoples call Turtle Island – the North American continent.

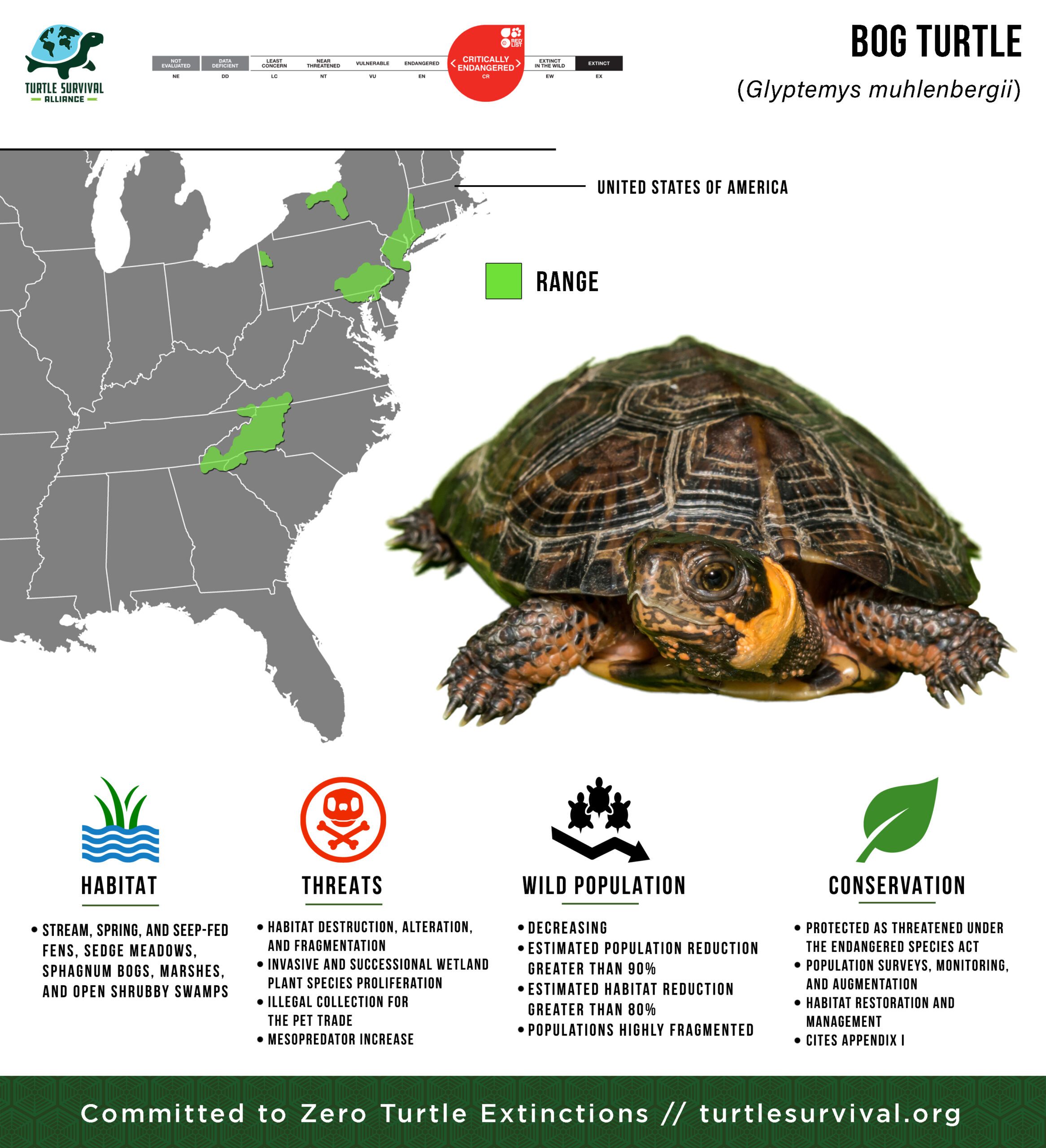

The bog turtle’s plight is a stark narrative of modern environmental pressures. Federally listed as Threatened by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service since 1997, and facing varying levels of state protection, its populations have plummeted due to a confluence of factors, primarily the relentless destruction and degradation of its highly specific wetland habitats. These aren’t just any wetlands; bog turtles thrive in open, sun-drenched fens, bogs, and wet meadows characterized by mucky, sphagnum-rich soils, shallow standing water, and a mosaic of sedges and grasses. Such unique ecosystems, essential for water filtration, flood control, and biodiversity, have historically been viewed as obstacles to development, leading to their widespread draining and conversion for agriculture, housing, and infrastructure.

Beyond direct habitat loss, remaining bog turtle strongholds face a barrage of threats. Hydrological changes, such as ditching and altered water tables, disrupt the delicate balance these wetlands require. Invasive plant species like Phragmites and multiflora rose aggressively outcompete native vegetation, shading out the open canopy bog turtles need for basking and nesting. Chemical runoff from surrounding agricultural and urban areas pollutes their water and food sources, while habitat fragmentation isolates populations, making genetic exchange difficult and increasing vulnerability to local extinctions. Poaching for the illegal pet trade further exacerbates the problem, with the turtle’s unique appearance and rarity making it a target for illicit collectors. Climate change, with its promise of altered precipitation patterns and increased storm intensity, adds another layer of uncertainty to an already fragile existence.

The concept of "Turtle Island" resonates deeply with the spirit of these conservation efforts. For many Indigenous nations, Turtle Island is more than a geographical descriptor; it is a spiritual and cultural foundation, a living entity formed on the back of a giant turtle, symbolizing creation, resilience, and the interconnectedness of all life. To restore the habitat of the bog turtle is, in essence, to honor this ancient understanding of stewardship, to mend the wounds inflicted upon the land, and to ensure that all creatures, great and small, can continue their journey on this sacred earth. This perspective imbues the scientific and practical work of restoration with a profound sense of responsibility and reverence.

Across the bog turtle’s range – from the northern populations stretching through New England, New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey, to the southern populations found in the Appalachian states of Maryland, Delaware, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia – a multi-faceted restoration strategy is being implemented. This strategy is not merely about preserving existing sites; it’s about actively rebuilding and revitalizing the very landscapes that define the bog turtle’s world.

A cornerstone of this effort is habitat acquisition and protection. Conservation organizations, land trusts, and state agencies work tirelessly to purchase key wetland parcels or establish conservation easements with private landowners. These legal agreements permanently protect the land from development and ensure that conservation-friendly management practices are employed. For instance, The Nature Conservancy and numerous local land trusts have secured thousands of acres of critical bog turtle habitat, often working in concert with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Partners for Fish and Wildlife program, which provides technical and financial assistance to private landowners.

Active habitat restoration forms the operational heart of these initiatives. This includes:

- Hydrological Restoration: Re-establishing natural water flows is paramount. This often involves removing old drain tiles, plugging ditches, and creating subtle depressions to encourage shallow, saturated conditions. Restoring the natural hydrology allows the growth of characteristic wetland vegetation, creating the mucky substrate essential for bog turtles to burrow for hibernation and estivation (a form of summer dormancy).

- Invasive Species Management: Aggressive invasive plants are systematically removed through a combination of manual pulling, targeted herbicide application, and in some cases, prescribed burning. This opens up the canopy, allowing sunlight to reach the wetland floor, which is crucial for bog turtle basking and for the growth of native plant communities. "Removing acres of dense Phragmites is grueling work," notes one conservation biologist, "but seeing native sedges and sphagnum moss return is incredibly rewarding, and it’s a direct benefit to the turtles."

- Native Plant Reintroduction: Following invasive species removal, native wetland plants are often reintroduced to accelerate ecological recovery. This can include species like tussock sedge, wool grass, and various sphagnum mosses, which provide food, shelter, and nesting sites.

- Controlled Burning: In certain fire-adapted wetland ecosystems, prescribed burns are used to maintain open conditions, prevent woody plant encroachment, and stimulate the growth of desirable native vegetation. This mimics natural disturbance regimes that historically kept these wetlands open.

- Buffer Zone Management: Recognizing that wetlands don’t exist in isolation, restoration efforts extend to managing the surrounding uplands. Creating vegetated buffer zones along wetland edges helps filter agricultural runoff, reduce erosion, and provide additional habitat and connectivity.

Beyond direct habitat work, population management strategies are also vital. "Head-starting" programs involve collecting bog turtle eggs or hatchlings, raising them in a protected environment for a year or two, and then releasing them back into suitable habitats. This increases their chances of survival past the highly vulnerable hatchling stage. Genetic studies are also conducted to understand population connectivity and inform translocation efforts, where turtles from robust populations might be moved to supplement struggling ones or establish new colonies in newly restored areas.

Community engagement and education are the unsung heroes of bog turtle conservation. Landowners are often crucial partners, and their willingness to embrace conservation easements and allow restoration work on their properties is indispensable. Volunteer groups dedicate countless hours to removing invasives, planting natives, and monitoring turtle populations. Educational programs raise awareness among the public, fostering a sense of stewardship and reducing the demand for illegal pet turtles. "We can restore the land all we want," explains a local land trust director, "but if the community doesn’t understand and value what we’re doing, the long-term success will always be at risk."

Despite the dedication, significant challenges remain. Funding for such labor-intensive, long-term projects is always a concern. The sheer scale of historical wetland degradation means that restoration efforts are often playing catch-up. The insidious effects of climate change introduce uncertainties that demand adaptive management strategies. Yet, there are triumphs. In several states, successful head-starting programs have bolstered local populations. Restored wetlands are showing signs of renewed ecological function, attracting not only bog turtles but also a host of other wetland-dependent species. These pockets of success serve as powerful affirmations of the possibility of ecological recovery.

The future of bog turtle conservation on Turtle Island is a testament to the enduring human capacity for repair and renewal. It demands continued vigilance, scientific innovation, and an unwavering commitment to the intricate web of life. The bog turtle, with its unassuming presence and demanding habitat, forces us to confront the health of our most vital wetlands. Its survival is not merely about one species; it is about the resilience of entire ecosystems, the purity of our water, and the very legacy we choose to leave for future generations on this shared continent. By restoring its mucky, sun-drenched homes, we are not just saving a turtle; we are affirming our profound connection to Turtle Island and all its inhabitants.