Guardians of Green: The Enduring Wisdom of Turtle Island’s Indigenous Plant Knowledge

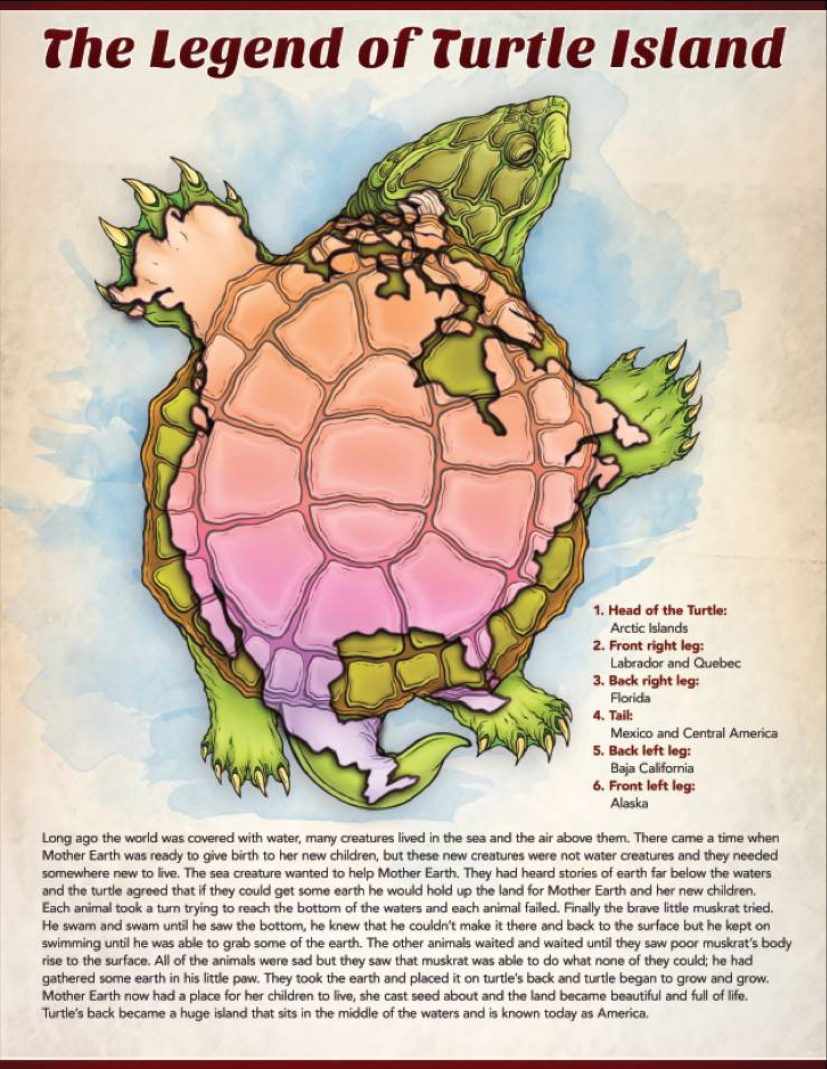

For millennia, Indigenous peoples across Turtle Island – the ancestral name for North America – have cultivated an unparalleled, intricate understanding of the plant kingdom. This profound knowledge, often termed Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), is far more than a collection of facts; it is a holistic, intergenerational philosophy of reciprocity, stewardship, and deep kinship with the natural world. It is a living library, passed down through stories, ceremonies, and hands-on practice, offering invaluable insights for contemporary challenges from climate change to sustainable agriculture.

The foundation of Indigenous plant knowledge rests on meticulous, multi-generational observation and experimentation. Unlike Western scientific paradigms that often isolate variables, Indigenous knowledge embraces the interconnectedness of all life. Plants are not just resources; they are relatives, teachers, and providers, each with a spirit and a specific role within the ecosystem. This perspective fosters a deep sense of responsibility and respect, ensuring that harvesting is done sustainably, with gratitude and an eye towards future generations.

A Living Pharmacy: Medicinal Plants

One of the most widely recognized facets of Indigenous plant knowledge is its extensive pharmacopoeia. Long before the advent of modern pharmaceuticals, Indigenous healers understood the medicinal properties of countless plants. Willow bark, for instance, known to many Indigenous nations, contains salicin – the active ingredient in aspirin – and was traditionally used to alleviate pain and fever. Echinacea, a powerful immune booster, was widely employed for infections and wounds.

Tobacco (Nicotiana rustica), while often associated with recreational use today, holds immense spiritual significance for many Indigenous cultures. It is a sacred plant, used in ceremonies, offerings, and prayers, believed to carry thoughts and intentions to the Creator. Its medicinal applications also include pain relief and anti-inflammatory properties when used topically or in specific preparations.

The knowledge of these remedies was not simply about identifying a plant for a specific ailment. It encompassed the precise timing of harvest, the specific part of the plant to use (root, leaf, flower), the method of preparation (tea, poultice, smoke), and the spiritual context of healing. Healers understood the subtle energetic qualities of plants and their interactions within the human body, recognizing that true healing addressed not only physical symptoms but also spiritual and emotional well-being. This holistic approach continues to inform Indigenous health practices today, often complementing Western medicine.

Sustenance and Innovation: Food Systems

Indigenous peoples were master agriculturalists and foragers, developing sophisticated food systems that sustained thriving civilizations for thousands of years. The iconic "Three Sisters" – corn, beans, and squash – exemplifies a highly efficient and sustainable polyculture system. Corn provides a stalk for beans to climb, beans enrich the soil with nitrogen, and squash vines spread across the ground, shading out weeds and retaining moisture. This symbiotic relationship not only maximizes yield but also maintains soil health, a stark contrast to monoculture practices that deplete land.

Beyond cultivated crops, Indigenous communities had an encyclopedic understanding of wild edibles. From wild rice (Manoomin in Ojibwe), a staple grain carefully harvested and stewarded in the Great Lakes region, to various berries, nuts, tubers, and greens, every season brought a new bounty. Knowledge of processing these foods, such as leaching tannins from acorns or preparing camas bulbs, was crucial for nutrition and survival. The seasonal rounds of hunting, fishing, and gathering were intricately tied to the life cycles of plants, demonstrating a deep awareness of ecological rhythms. Maple syrup production, a tradition dating back centuries, showcases another ingenious method of sustainable harvesting and processing that continues to be a vital cultural and economic practice for many Eastern Woodland nations.

Material Culture and Technology

Plants were also the bedrock of Indigenous material culture and technology. The versatility of trees like cedar, birch, and spruce was harnessed for an astonishing array of purposes. Cedar, revered as the "tree of life" by many Pacific Northwest nations, was used for everything from massive longhouses and canoes to intricate weaving for clothing, baskets, and ceremonial objects. Its strength, rot resistance, and workability made it an indispensable resource.

Birch bark, with its waterproof and pliable qualities, was used to construct lightweight, durable canoes – a revolutionary mode of transportation across vast waterways. It also formed the basis for containers, shelters, and even written scrolls. Spruce roots were used for lashing, while various grasses and fibers were woven into mats, ropes, and clothing. This intimate knowledge of plant properties allowed for the development of sophisticated tools, shelters, and technologies perfectly adapted to diverse environments, all without external inputs or environmental degradation.

Ecological Stewardship and Land Management

Perhaps the most profound aspect of Indigenous plant knowledge is its role in ecological stewardship and land management. Indigenous peoples did not simply live on the land; they actively shaped and maintained healthy ecosystems. Practices like prescribed burning, often misunderstood by colonial settlers, were crucial for preventing catastrophic wildfires, promoting biodiversity, and enhancing the growth of culturally important plants. By mimicking natural fire cycles, Indigenous land managers cleared underbrush, enriched soil, and created mosaic landscapes that supported a wider variety of plant and animal life. It is estimated that Indigenous burning practices historically shaped over 100 million acres of North America annually.

"When you take care of the land, the land takes care of you," is a common teaching among many nations, encapsulating the philosophy of reciprocity. This extended to understanding plant succession, soil health, water cycles, and the intricate relationships between plants, animals, and climate. They cultivated "forest gardens," strategically managing specific areas to increase the abundance of desired species, creating landscapes that were both productive and ecologically robust. This proactive management contrasts sharply with the passive "wilderness" concept often imposed by colonial conservation models.

The Threat and The Resurgence

The arrival of European colonizers brought immense disruption to these sophisticated knowledge systems. Policies of forced assimilation, land dispossession, residential schools, and the suppression of Indigenous languages and cultural practices severely threatened the intergenerational transfer of plant knowledge. When an elder passes, it is often said, a library burns, and countless generations of ecological wisdom have been lost or are on the brink. The destruction of traditional territories through resource extraction further exacerbates this crisis.

Despite these devastating impacts, Indigenous plant knowledge is experiencing a powerful resurgence. Communities are actively revitalizing languages, which are intrinsically linked to plant names and their associated stories and uses. Cultural camps, intergenerational teaching initiatives, and "land back" movements are reconnecting youth with their ancestral lands and the plant wisdom held within them. Elders are tirelessly sharing their knowledge, and younger generations are embracing the responsibility to learn and perpetuate these vital traditions.

Modern Relevance and the Path Forward

In an era of unprecedented environmental crisis, Indigenous plant knowledge offers critical solutions and perspectives. As the world grapples with climate change, biodiversity loss, and food insecurity, the sustainable practices, ecological insights, and reciprocal philosophies embedded in TEK are proving invaluable. Indigenous land management techniques, like prescribed burning, are now being recognized and adopted by mainstream fire management agencies. Indigenous agricultural methods offer models for resilient and sustainable food production.

Moreover, the ethical framework of Indigenous knowledge – one of respect, gratitude, and responsibility – challenges the extractive and exploitative paradigms that have dominated industrial societies. Collaborations between Indigenous knowledge holders and Western scientists are increasingly common, leading to a richer, more holistic understanding of ecosystems and potential solutions. These partnerships, however, must be built on a foundation of respect, equity, and Indigenous sovereignty, ensuring that Indigenous intellectual property is protected and that benefits are shared equitably.

The plant knowledge of Turtle Island’s Indigenous peoples is not a relic of the past; it is a dynamic, living system of understanding that continues to evolve and adapt. It represents a profound testament to human ingenuity, resilience, and the enduring power of a deep, reciprocal relationship with the natural world. As we look to the future, listening to and learning from these guardians of green is not just an act of reconciliation; it is an essential step towards a more sustainable and harmonious existence for all.