Echoes of Assimilation: The Enduring Scars of Intergenerational Trauma on Turtle Island

Turtle Island, the ancestral land of Indigenous peoples across North America, bears witness to a profound and enduring wound: intergenerational trauma. This isn’t merely a historical footnote but a living, breathing scar, passed down through generations, shaping the lives of individuals, families, and communities. It is the insidious legacy of centuries of colonization, cultural genocide, and systemic oppression, manifesting in complex health disparities, social challenges, and a persistent struggle for identity and healing. To understand the present realities faced by Indigenous peoples, one must first confront the historical atrocities that laid its foundation.

The primary instrument of this trauma was the residential school system, operational in Canada from the 1830s until the last school closed in 1996, and similarly in the United States as boarding schools. These institutions, often run by churches and funded by the government, were designed with a singular, devastating purpose: to "kill the Indian in the child." Over 150,000 Indigenous children in Canada alone were forcibly removed from their families, communities, and cultures, often as young as four years old. They were forbidden to speak their languages, practice their ceremonies, or acknowledge their heritage. Physical, emotional, and sexual abuse was rampant. Nutritional experiments were conducted, and many children died without their families ever knowing their fate or burial site.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC), established in 2008, meticulously documented these horrors, concluding that the residential school system amounted to "cultural genocide." Its 2015 final report highlighted how these institutions intentionally undermined Indigenous culture and identity, severing children from the very fabric of their being. This wasn’t an isolated incident but a deliberate policy to assimilate Indigenous peoples into settler society, stripping them of their land, resources, and sovereignty.

The Sixties Scoop, another egregious chapter, saw thousands of Indigenous children apprehended by child welfare services and adopted into non-Indigenous families, both within Canada and internationally. This practice further disrupted family structures, severed cultural ties, and compounded the trauma initiated by residential schools, leaving many adoptees with profound identity crises and a deep sense of loss. Similar practices occurred in the United States, where the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) of 1978 was enacted specifically to prevent the mass removal of Indigenous children from their families and tribes.

The immediate impacts of these policies were catastrophic for the survivors. Many emerged from residential schools deeply traumatized, lacking parenting skills due to their own experiences of abuse and neglect, and alienated from their own cultures. They struggled with severe mental health issues, including PTSD, depression, and anxiety. Substance abuse became a pervasive, albeit maladaptive, coping mechanism for unbearable pain. The cycle of violence, learned in the schools, often manifested in their own homes and communities.

However, the insidious nature of intergenerational trauma lies in its ability to transcend direct experience. It is not merely the trauma of a generation, but the trauma between generations. Scientific understanding, particularly in the field of epigenetics, is beginning to shed light on how severe stress and trauma can alter gene expression, potentially passing down vulnerabilities to subsequent generations. While the exact mechanisms are still being explored, the observable impacts are undeniable.

Children of residential school survivors often grow up in environments marked by their parents’ unresolved trauma. They may experience a lack of secure attachment, emotional numbness, or an inherited sense of shame and loss. The silence surrounding the residential school experience, often a protective mechanism for survivors, can leave younger generations feeling disconnected from their past, yet burdened by an unspoken weight. As one Elder poignantly put it, "We carry the pain of our grandparents in our bones."

The manifestations of this intergenerational trauma are stark and pervasive across Turtle Island:

- Mental Health Crises: Indigenous communities face disproportionately high rates of mental health challenges, including PTSD, depression, anxiety disorders, and suicide. Suicide rates among Indigenous youth are significantly higher than the national average in both Canada and the U.S., a direct reflection of the unresolved historical and ongoing trauma.

- Substance Abuse: Alcohol and drug abuse remain significant challenges, often used as self-medication for deep-seated pain and a lack of healthy coping mechanisms, exacerbating cycles of poverty and violence.

- Family Breakdown and Violence: The disruption of traditional family structures and parenting practices, combined with the legacy of abuse, contributes to higher rates of domestic violence, child neglect, and involvement with child welfare systems.

- Health Disparities: Intergenerational trauma contributes to chronic stress, which has been linked to a range of physical health issues, including higher rates of diabetes, heart disease, and other chronic illnesses among Indigenous populations. Access to adequate healthcare, compounded by systemic racism, further exacerbates these disparities.

- Loss of Language and Culture: The deliberate suppression of Indigenous languages and cultural practices has resulted in a critical loss of traditional knowledge, identity, and spiritual connection, which are vital for well-being.

- Systemic Racism and Poverty: The historical dispossession of land and resources, coupled with ongoing discrimination in education, employment, and justice systems, perpetuates cycles of poverty and marginalization, creating continuous re-traumatization. Indigenous peoples are overrepresented in incarceration rates, and face significant barriers to economic and social equity.

Despite the profound weight of this historical burden, the narrative of Indigenous peoples on Turtle Island is not solely one of victimhood. It is equally a story of immense resilience, cultural resurgence, and an unwavering commitment to healing. Indigenous communities are actively leading the charge in developing culturally appropriate healing initiatives that draw upon traditional knowledge, ceremonies, and land-based practices.

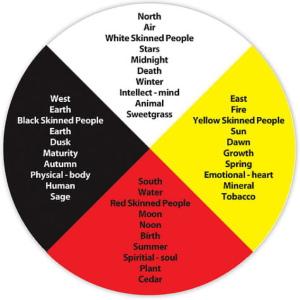

- Cultural Revitalization: Reclaiming languages, revitalizing ceremonies, engaging in traditional arts, and reconnecting with ancestral lands are powerful acts of healing and self-determination. These practices restore a sense of identity, belonging, and spiritual connection that colonization sought to erase.

- Elders and Knowledge Keepers: The wisdom of Elders and Knowledge Keepers is crucial in guiding healing journeys, sharing traditional teachings, and providing cultural continuity.

- Community-Led Initiatives: Many Indigenous communities are developing their own mental health programs, youth mentorship initiatives, and family support services that are rooted in their specific cultural contexts and needs.

- Self-Determination and Nation-Building: The pursuit of self-governance, land rights, and economic independence empowers Indigenous nations to rebuild their communities, address systemic inequities, and create a future based on their own values and aspirations.

- Truth and Reconciliation: The TRC’s 94 Calls to Action in Canada, and the ongoing work related to the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) Calls for Justice, provide a framework for governments, institutions, and individuals to engage in acts of reconciliation, truth-telling, and justice. These calls emphasize the need for systemic change, education, and genuine partnership.

The journey of healing from intergenerational trauma is long, complex, and deeply personal, yet intrinsically communal. It demands not just understanding of the past, but active engagement in the present. It requires non-Indigenous society to acknowledge the profound impact of its colonial history and to commit to genuine reconciliation, which goes beyond apologies to include concrete actions that support Indigenous self-determination, equity, and the revitalization of their cultures. The echoes of assimilation still resonate across Turtle Island, but they are increasingly joined by the powerful voices of healing, resilience, and hope, striving to build a future where all children can grow up free from the shadows of their ancestors’ pain.