Beyond the Jade Curtain: Unearthing the Northern Threads in Ancient Mesoamerica

For centuries, the ancient civilizations of Mesoamerica – with their colossal pyramids, intricate glyphs, sophisticated calendars, and bustling urban centers – have captivated the human imagination. From the enigmatic Olmec to the star-gazing Maya, the urban planners of Teotihuacan to the mighty Aztec, these societies are often portrayed as self-contained marvels, distinct cradles of civilization flourishing in a world apart. Yet, a deeper archaeological gaze reveals a more nuanced truth: Mesoamerica was far from an isolated cultural island. Its vibrant tapestry was interwoven with threads reaching far beyond its traditional boundaries, particularly from the arid and semi-arid lands to its north.

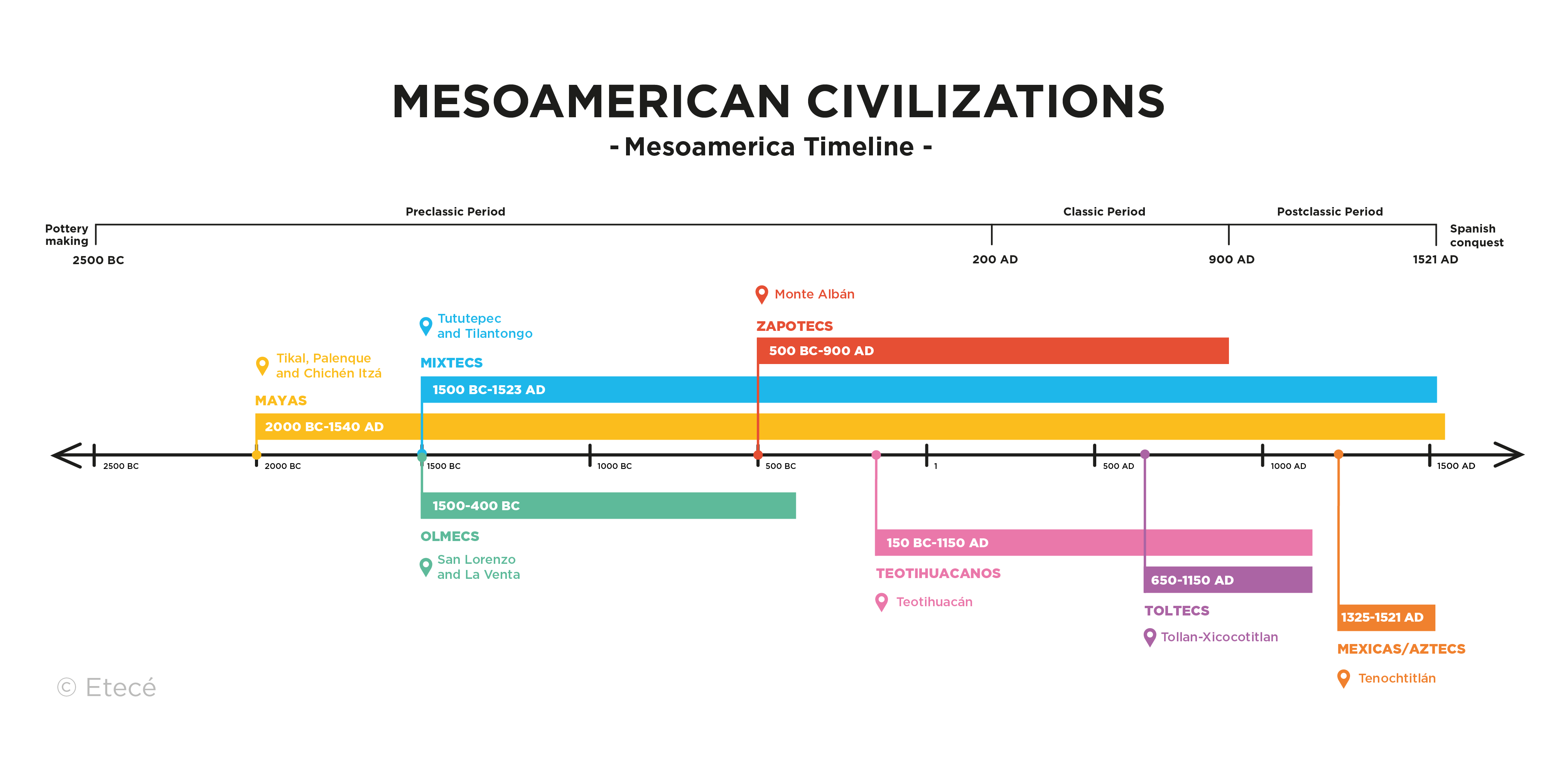

The concept of "Mesoamerica" itself, coined by Paul Kirchhoff in 1943, delineates a cultural area sharing a complex suite of traits: maize agriculture, stepped pyramids, the ritual ballgame, a 260-day calendar, and a rich pantheon of deities, among others. North of this cultural heartland lay the vast, often harsh, expanse of Aridamerica, home to diverse groups ranging from settled agriculturalists in the American Southwest to nomadic hunter-gatherers often labeled collectively as the "Chichimeca." Traditionally, the interaction between these two spheres was viewed as minimal, a one-way street where Mesoamerican innovations like maize gradually diffused north. However, a growing body of archaeological evidence is challenging this paradigm, suggesting a dynamic, often reciprocal, relationship where northern influences significantly shaped Mesoamerican development, particularly during its later periods.

One of the most compelling lines of evidence for northern interaction comes through trade networks. While Mesoamerica exported precious goods like obsidian, jade, and cacao southwards, the north provided its own coveted commodities. Perhaps the most iconic northern export found in Mesoamerica is turquoise. This striking blue-green stone, primarily sourced from mines in the American Southwest (such as the Cerrillos Mine in New Mexico), has been unearthed in significant quantities at major Mesoamerican sites. For instance, archaeological finds at Teotihuacan, the sprawling metropolis of central Mexico, include turquoise mosaics and adornments, suggesting a long-distance trade route stretching thousands of kilometers. Even more strikingly, caches of turquoise have been recovered at Postclassic Maya sites like Chichen Itza, indicating its enduring value and the extensive networks that brought it south. The presence of such a distant material speaks volumes about the established routes and the economic and symbolic value placed on goods from the north.

Conversely, the presence of tropical Mesoamerican goods in the north also underscores this deep connection. Perhaps one of the most vivid illustrations of this cross-cultural exchange comes from the presence of scarlet macaws – native to tropical Mesoamerica – in sites across the American Southwest, notably at Chaco Canyon and especially Paquimé (Casas Grandes). These exotic birds, likely prized for their vibrant feathers used in rituals and regalia, were not merely traded but actively bred in captivity at sites like Paquimé, which served as a crucial intermediary between Mesoamerica and the Southwest. The elaborate macaw pens and specialized feeding bowls found at Paquimé testify to a sophisticated system of procurement and management of these tropical species, highlighting a demand that directly connected northern communities to the Mesoamerican heartland.

Beyond mere goods, the north also played a role in the diffusion of agricultural practices and plant varieties. While maize cultivation originated in Mesoamerica and spread northward, the reciprocal movement of specific varieties or agricultural techniques is also plausible. Cotton, for example, grown in the American Southwest, may have seen its cultivation influenced or enhanced by interactions with northern peoples. The exchange of knowledge regarding drought-resistant crops or irrigation techniques suitable for arid environments could have been invaluable.

However, the most profound and transformative northern influences often manifest in the Postclassic period (c. 900-1521 CE), following the collapse of many Classic-era Mesoamerican states. This era saw significant population movements and the rise of new, often militaristic, powers. The lands to the north, particularly the semi-arid frontier known as the "Chichimeca," were home to groups often depicted in Mesoamerican ethnohistorical sources as nomadic, fierce, and less "civilized." Yet, these "barbarian" groups were not simply a threat; they were also a source of innovation and demographic shifts that profoundly reshaped Mesoamerica.

The Toltec civilization, which rose to prominence in central Mexico after the fall of Teotihuacan, is a prime example of this northern infusion. While their exact origins are debated, many scholars believe the Toltec had strong connections to groups from the northern frontier, perhaps incorporating Chichimeca elements into their core. Their capital, Tula, exhibited a distinctly militaristic iconography and a focus on warrior orders, elements that became more prominent in Postclassic Mesoamerica. The legendary figure of Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, a Toltec ruler, reflects a synthesis of Mesoamerican religious thought with potentially new political ideologies. The influence of the Toltec spread far and wide, famously impacting Maya sites like Chichen Itza, where architectural styles, iconography (such as the feathered serpent Kukulcan and Chac Mool figures), and even the layout of major structures show clear Toltec inspiration. This wasn’t merely trade; it was a deep cultural imprint, suggesting the movement of people and ideas on a grand scale.

Further north, the rise of Paquimé (Casas Grandes) in present-day Chihuahua, Mexico, around 1200 CE, serves as a powerful testament to the interconnections. Paquimé was an urban center that uniquely blended Mesoamerican and Southwestern cultural traits. It featured multi-story adobe apartment complexes, Mesoamerican-style ballcourts, platform mounds, and sophisticated irrigation systems. Its pottery, while distinctive, also shows design elements reminiscent of both Mesoamerican and Southwestern traditions. The presence of Mesoamerican ritual paraphernalia, such as copper bells and marine shells from the Gulf of California, alongside macaw breeding, solidifies its role as a key conduit for goods, ideas, and potentially people between the two regions. Paquimé’s collapse around 1450 CE led to another ripple effect, with its inhabitants potentially dispersing and influencing surrounding communities.

The Chichimeca themselves, initially seen as an undifferentiated mass of "savages," played a continuous role in the dynamics of central Mexico. As settled Mesoamerican populations expanded, they constantly interacted with these northern groups, sometimes absorbing them, sometimes being raided by them, and sometimes adopting their practices. The Aztec Empire, which dominated the late Postclassic, explicitly traced its lineage to Chichimeca ancestors, claiming a nomadic, warrior past that they later "civilized" in the Valley of Mexico. This narrative, while serving to legitimize their rule, also acknowledges a fundamental northern component in their identity and martial prowess. The constant pressure and occasional influx of northern groups undoubtedly contributed to the militarization and shifting political landscapes characteristic of Postclassic Mesoamerica.

One of the challenges in understanding northern influence lies in distinguishing direct adoption from parallel development or convergent evolution. However, the sheer volume of archaeological evidence – from specific artifacts and architectural styles to shared iconographic motifs and ethnohistorical accounts – points overwhelmingly to genuine and significant interaction. The idea of Mesoamerica as a static, isolated entity is increasingly untenable.

As archaeologist Dr. Michael E. Smith notes, "The long-standing notion of Mesoamerica as an isolated, self-contained cultural block is increasingly giving way to a more dynamic picture of interaction and influence across vast distances." This evolving understanding encourages us to view ancient North America not as a collection of disconnected cultural zones, but as a vast, interconnected tapestry where ideas, goods, and people flowed across perceived boundaries.

In conclusion, the ancient civilizations of Mesoamerica, while undeniably unique and brilliant in their achievements, were not born in a vacuum. From the precious turquoise adorning its elites to the militaristic ideologies of the Toltec, and the crucial intermediary role played by sites like Paquimé, the influence of the northern lands profoundly shaped Mesoamerican societies. The archaeological record, therefore, paints a picture not of isolation, but of a dynamic, interconnected ancient America, where the "jade curtain" of Mesoamerica was frequently drawn back, revealing a rich and complex web of interactions with its northern neighbors, forever enriching its cultural landscape.

.jpeg?w=200&resize=200,135&ssl=1)