The Sacred Grain and Enduring Wisdom: Wild Rice Harvesting Through Ojibwe Traditional Ecological Knowledge

In the shallow, sun-dappled waters of the Great Lakes region, where the ancient forests meet shimmering lakes and winding rivers, a sacred plant has nourished the Anishinaabe people – the Ojibwe, or Chippewa – for millennia. This plant is Manoomin, commonly known as wild rice (Zizania aquatica and Zizania palustris), a grain that is far more than just food. It is a spiritual relative, a cultural cornerstone, and a powerful symbol of resilience, woven deeply into the fabric of Ojibwe identity and their Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK).

Wild rice harvesting, a practice that unfolds each late summer and early autumn, is not merely an agricultural pursuit; it is a profound act of communion, a living testament to an intricate system of knowledge passed down through generations. This journalistic exploration delves into the heart of Manoomin harvesting, examining how Ojibwe TEK informs every aspect of this vital tradition, from understanding the ecosystem to navigating modern threats, and ultimately, safeguarding a way of life.

Manoomin: The Food That Grows on Water

For the Anishinaabe, Manoomin is literally "the good berry" or "the good grain." Its significance is enshrined in prophecy, which guided their ancestors westward from the Atlantic coast: "Go to the place where food grows on water." This prophecy led them to the bountiful wild rice beds of the Great Lakes, establishing a deep and enduring connection. Rich in protein, fiber, and essential minerals, Manoomin was, and remains, a dietary staple, crucial for winter survival and ceremonial feasts.

But its value extends far beyond nutrition. Manoomin connects the Ojibwe to their ancestors, to the land, and to the spiritual realm. "Manoomin is life," explains Joe Nayquonabe, an Ojibwe elder and harvester from the Mille Lacs Band. "It’s not just food; it’s our identity. When you’re out on the water, harvesting, you feel the spirits of your ancestors with you. They taught us how to care for it." This sentiment encapsulates the core of TEK – a holistic understanding that transcends mere scientific data, integrating spiritual, cultural, and practical knowledge.

The Art of Sustainable Harvesting: TEK in Action

The Ojibwe method of harvesting Manoomin is a masterclass in sustainable practice, developed over centuries of intimate observation and interaction with the plant and its environment. Unlike commercially farmed rice, which is often grown in monoculture paddies, traditional wild rice is harvested from natural, dynamic ecosystems.

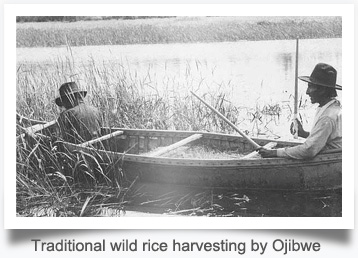

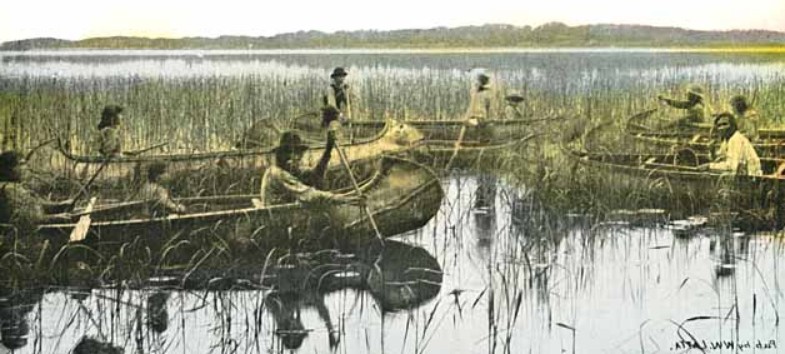

The process begins not with planting, but with patient observation. Harvesters, often working in pairs in shallow-draft canoes, watch the rice beds throughout the summer. They understand the subtle cues: the water levels, the strength of the winds, the presence of various birds and insects, all of which indicate the health and readiness of the rice. This intuitive, yet highly precise, knowledge is a hallmark of TEK.

"You don’t just go out and take," emphasizes Sarah Beaulieu, a young Ojibwe harvester learning from her elders. "You have to know when the rice is ready, and you have to leave enough for the next year, and for the animals. The rice teaches you patience, and respect."

The actual harvesting involves a rhythmic, almost meditative dance. One person guides the canoe through the dense stands of rice, while the other, using two thin, smooth "knocking sticks" (often made of cedar or maple), gently bends the ripe rice stalks over the canoe. With a soft tap of the second stick, the mature grains fall into the bottom of the canoe. This method is crucial: only the ripest grains, those ready to detach, are collected, leaving the unripe kernels to mature and ensuring ample reseeding for future harvests. This gentle approach minimizes disturbance to the plant and its aquatic habitat, embodying the principle of reciprocity central to Ojibwe worldview.

After the harvest, the Manoomin undergoes a traditional processing sequence:

- Parching: The grains are slowly roasted over a fire, which dries them, prevents spoilage, and helps loosen the hull.

- Jigging/Threshing: The parched rice is gently danced upon or beaten to remove the outer hull. Historically, this was done by stepping on the rice in a pit, sometimes with special moccasins.

- Winnowing: The final step involves tossing the rice in a birch bark tray or a blanket, allowing the wind to carry away the lighter chaff, leaving behind the clean, nutritious kernels.

Each step is laborious, often a communal effort, reinforcing social bonds and the intergenerational transfer of knowledge. Children watch, learn, and eventually participate, absorbing not just the techniques but also the spiritual reverence for Manoomin.

Manoomin as an Ecological Barometer: Warnings from the Water

Ojibwe TEK recognizes Manoomin as a sentinel species, an early warning system for the health of the broader ecosystem. Wild rice is incredibly sensitive to changes in water quality, depth, and flow. It thrives in specific conditions – clear, shallow water with a slow current and a mucky bottom – and its decline signals deeper environmental problems.

"When the rice beds are struggling, it means the water is struggling, and when the water is struggling, we are struggling," says an elder from the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa. This direct correlation highlights how Indigenous knowledge systems often provide a more holistic and immediate understanding of environmental degradation than isolated scientific studies.

Modern Threats to an Ancient Tradition

Today, Manoomin and the Ojibwe tradition of harvesting face unprecedented challenges, many of which are a direct consequence of colonial impacts and industrial development.

- Climate Change: Erratic weather patterns, including extreme floods and droughts, disrupt the delicate life cycle of wild rice. Fluctuating water levels can drown young plants or leave developing grains exposed to drying winds and hungry birds.

- Invasive Species: Non-native plants like Phragmites australis (common reed) aggressively outcompete wild rice, forming dense monocultures that choke out native vegetation. Invasive common carp (Cyprinus carpio) uproot wild rice plants while foraging, clouding the water and destroying crucial habitat.

- Water Pollution: Industrial runoff, agricultural chemicals, and municipal wastewater discharge degrade water quality, introducing toxins and excess nutrients that can be lethal to sensitive wild rice. Mining operations, such as proposed copper-nickel mines, pose significant threats through potential acid mine drainage.

- Habitat Loss and Alteration: Shoreline development, dam construction, and dredging destroy or alter the specific shallow-water habitats where Manoomin thrives.

- Commercial Exploitation: Non-traditional, mechanized harvesting methods, often used in commercial operations, can be destructive, failing to ensure reseeding and damaging the delicate ecosystem.

These threats are not merely ecological; they are direct attacks on Ojibwe cultural identity, food sovereignty, and treaty rights. The fight to protect Manoomin is therefore a fight for cultural survival and self-determination.

Guardians of the Grain: Ojibwe Advocacy and Resilience

In response to these existential threats, Ojibwe communities are actively engaged in multifaceted efforts to protect Manoomin, drawing upon their TEK and asserting their inherent rights.

Treaty Rights and Legal Battles: Many Ojibwe bands hold federally recognized treaty rights to hunt, fish, and gather in their ceded territories. These rights are increasingly being invoked in legal battles to protect wild rice. A prominent example is the ongoing struggle against Enbridge’s Line 3 crude oil pipeline, which crosses through critical wild rice beds in northern Minnesota. The Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, among others, has been at the forefront of this fight, arguing that the pipeline threatens their treaty-protected ability to harvest Manoomin.

"Rights of Manoomin": In a groundbreaking move, the White Earth Nation in Minnesota passed a law in 2018 recognizing the "Rights of Manoomin" to exist, flourish, and evolve. This legal framework, inspired by the "Rights of Nature" movement, grants wild rice legal personhood, allowing the tribe to sue on its behalf to protect it from environmental harm. This approach fundamentally shifts the legal paradigm, moving away from viewing nature as mere property.

Restoration and Management: Ojibwe communities are actively engaged in restoration projects, reseeding wild rice in degraded areas, and working with environmental scientists to develop strategies for managing invasive species and improving water quality. This collaborative approach demonstrates how TEK can inform and enrich contemporary scientific efforts, creating more effective and culturally appropriate conservation strategies.

Food Sovereignty and Cultural Revitalization: Protecting Manoomin is central to the broader Indigenous food sovereignty movement, which seeks to reclaim traditional food systems and ensure access to healthy, culturally appropriate foods. By revitalizing wild rice harvesting, communities are not only securing a vital food source but also strengthening cultural identity, promoting intergenerational learning, and fostering a deeper connection to their ancestral lands.

A Call for Reciprocity

The story of Ojibwe wild rice harvesting is a powerful reminder of the profound wisdom embedded in Traditional Ecological Knowledge. It highlights a relationship with the natural world built on reciprocity, respect, and deep understanding, rather than exploitation. As the world grapples with escalating environmental crises, the Ojibwe’s enduring stewardship of Manoomin offers invaluable lessons.

Their struggle to protect this sacred grain is not just for themselves; it is a fight for the health of the waters, the resilience of ecosystems, and the possibility of a more sustainable future for all. Listening to the wisdom of those who have lived in harmony with the land for millennia is not merely an act of cultural respect, but an urgent necessity for ecological survival. The gentle rustle of Manoomin in the autumn breeze carries not just the promise of sustenance, but the echoes of ancient wisdom, whispering a path forward.