Symphony in the Soil: The Enduring Wisdom of Native American Agriculture and the Three Sisters

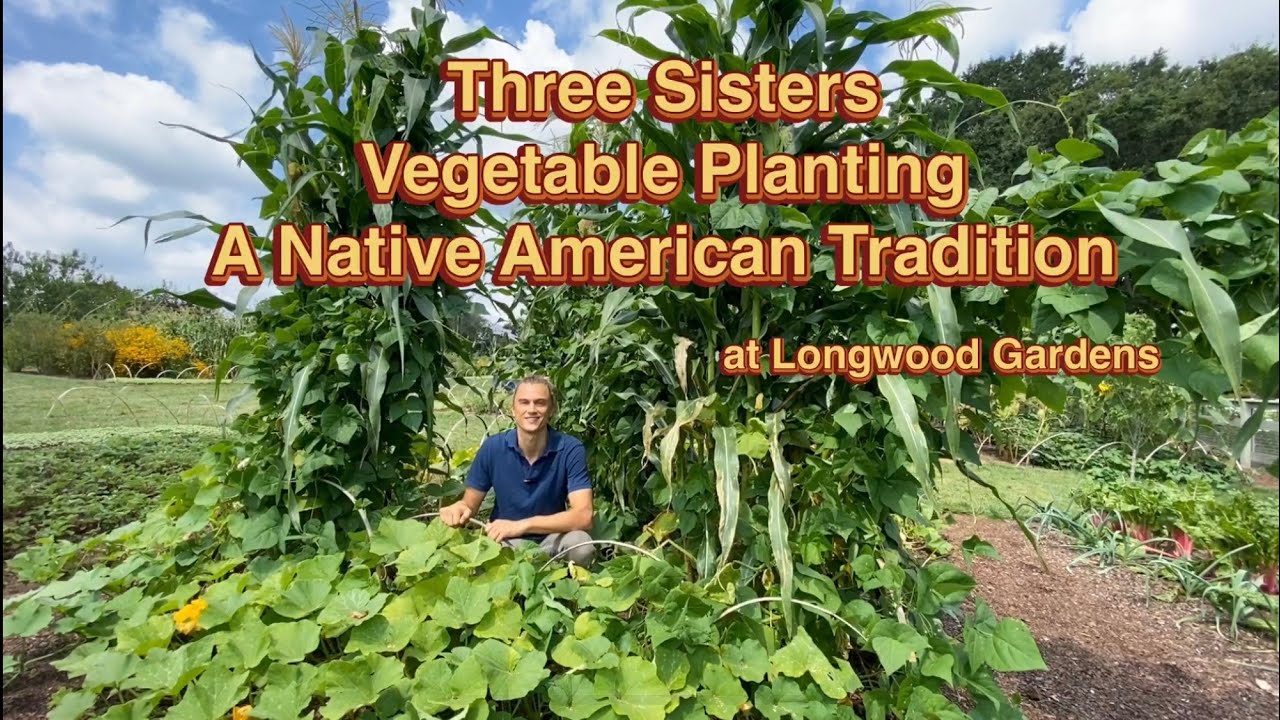

For millennia, long before the advent of industrial agriculture, Indigenous peoples across North America cultivated sophisticated farming systems that not only sustained vibrant communities but also fostered ecological balance. At the heart of many of these traditions lay a profound understanding of reciprocity with the land, nowhere more beautifully exemplified than in the practice of "The Three Sisters": corn, beans, and squash. This ingenious polyculture is far more than just companion planting; it is a living testament to a holistic approach to food production, nutrition, and community well-being that holds invaluable lessons for our modern world.

The narrative of Native American agriculture often begins with the humble corn plant, Zea mays. Domesticated in Mesoamerica thousands of years ago, corn’s journey north transformed societies, laying the foundation for complex civilizations from the Pueblo peoples of the Southwest to the Iroquois Confederacy in the Northeast. But it was in its symbiotic relationship with beans and squash that corn truly reached its potential, creating a dynamic trio that optimized growth, enhanced soil fertility, and provided a nutritionally complete diet.

The Older Sister: Corn – The Pillar of Life

Corn, the eldest sister, stands tall and proud, providing the central structure for the entire system. Its sturdy stalks act as natural trellises, offering the climbing bean vines a pathway to sunlight. But corn’s role extends beyond mere physical support. It is a carbohydrate powerhouse, providing essential energy that formed the caloric backbone of Native diets.

The selection and breeding of corn varieties over thousands of years by Indigenous farmers is a marvel of agricultural science. From flint corn suitable for cold climates to drought-resistant varieties for arid lands, the genetic diversity cultivated was staggering. "Our ancestors didn’t just plant corn; they listened to it, understood its needs, and nurtured its spirit," explains a hypothetical elder, emphasizing the deep, intuitive connection. "Each kernel held generations of knowledge." This meticulous stewardship ensured resilience and adaptability, traits sorely lacking in today’s monoculture systems.

The Middle Sister: Beans – The Earth’s Fertiliser

Climbing gracefully up the corn stalks, the bean plant (Phaseolus vulgaris) is the middle sister, a silent but potent contributor to the trio’s success. Beans are legumes, renowned for their ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen into the soil through a process carried out by bacteria in their root nodules. Nitrogen is a vital nutrient for plant growth, and by making it available, the beans naturally fertilize the soil, reducing the need for external inputs and benefiting both the corn and squash.

Beyond their role as a living fertilizer factory, beans provide a critical nutritional complement to corn. While corn is rich in carbohydrates, it is low in the amino acids lysine and tryptophan. Beans, however, are abundant in these very amino acids, and together, corn and beans form a complete protein, offering a dietary synergy that sustained healthy populations for millennia. This sophisticated understanding of nutrition, long before modern biochemistry, highlights the profound empirical knowledge possessed by Native American farmers.

The Younger Sister: Squash – The Ground’s Protector

Spreading across the ground beneath the towering corn and climbing beans, the squash plant (Cucurbita) is the youngest sister, playing a crucial protective role. Its broad, sprawling leaves create a natural mulch, shading the soil and suppressing weed growth, thereby reducing competition for nutrients and water. This ground cover also helps to retain soil moisture, a critical advantage in many environments, especially during dry spells.

Furthermore, the prickly stems and leaves of many squash varieties act as a natural deterrent to common pests, guarding the more vulnerable corn and bean plants. The squash itself provides a rich source of vitamins, minerals, and fiber, and its hard rind allows for long-term storage, providing sustenance through the lean winter months. From summer squash eaten fresh to winter varieties like butternut and pumpkin, the diversity of squash cultivated was immense, each adapted for specific uses and climates.

The Symbiotic Dance: More Than the Sum of Its Parts

The brilliance of the Three Sisters system lies not just in the individual contributions of each plant but in their profound symbiotic relationship. The corn provides the structure; the beans provide the nitrogen; the squash provides ground cover and pest deterrence. This complex polyculture creates a mini-ecosystem that mimics natural forest edges, enhancing biodiversity both above and below ground.

"It’s a dance, a conversation between plants," says Dr. Jane Mt. Pleasant, a Tuscarora scholar and expert in Indigenous agriculture. "They support each other, they feed each other, they protect each other. It’s a perfect example of how interconnected life truly is." This intercropping technique is a testament to the deep observational skills and ecological understanding developed over countless generations. It is a system that regenerates the soil rather than depleting it, ensuring fertility for future harvests.

Beyond the Sisters: A Holistic Approach

While the Three Sisters system is iconic, it represents only one facet of the diverse and sophisticated agricultural practices of Native Americans. Indigenous farmers developed a wide array of techniques tailored to their specific environments:

- Polyculture and Biodiversity: Beyond the core trio, many communities incorporated other plants into their fields, such as sunflowers (which attract pollinators and deter pests), amaranth, tobacco, and various herbs. This biodiversity created resilient ecosystems, reducing the risk of widespread crop failure due to pests or disease.

- Water Management: In arid regions, like the American Southwest, complex irrigation systems, including canals and check dams, were developed by Ancestral Puebloans and other groups to channel and conserve water. Dry farming techniques, such as waffle gardens designed to capture and hold precious rainfall, also demonstrated remarkable ingenuity.

- Soil Health and Fertility: In addition to nitrogen-fixing beans, farmers utilized composting, crop rotation, and controlled burning to enrich and maintain soil health. The careful application of fish or other organic matter as fertilizer was also practiced in many areas.

- Seed Saving and Adaptation: The annual ritual of seed saving was central to Indigenous agriculture. Farmers meticulously selected seeds from the strongest, most productive, and best-adapted plants, ensuring the continuation and improvement of their crop varieties. This practice fostered incredible genetic diversity and resilience, a stark contrast to the monoculture dependence of modern industrial agriculture.

Cultural and Spiritual Dimensions

Native American agriculture was never merely about producing food; it was deeply interwoven with culture, spirituality, and community identity. The act of planting, tending, and harvesting was often accompanied by ceremonies, prayers, and songs of gratitude. The land was not viewed as a resource to be exploited but as a living entity, a relative, to be treated with respect and reciprocity.

"We don’t own the land; we belong to the land," is a common Indigenous teaching. This philosophy of stewardship, rather than ownership, guided agricultural practices. The Three Sisters were often personified and revered, embodying the virtues of interdependence, generosity, and the circle of life. Food was a gift from the Creator, and its cultivation was a sacred responsibility.

The Legacy and Modern Relevance

The arrival of European colonizers brought devastating changes. Traditional agricultural lands were seized, Indigenous farming practices were suppressed or replaced with monocultures, and invaluable seed banks were lost. The forced relocation of communities further disrupted ancient knowledge systems, leading to food insecurity and the loss of traditional diets.

Despite this history of dispossession, the wisdom of Native American agriculture endures. Today, there is a powerful resurgence of interest in these traditional methods. Farmers, environmentalists, and food sovereignty advocates are increasingly recognizing the profound relevance of Indigenous agricultural practices for addressing contemporary challenges:

- Sustainable Agriculture: The Three Sisters model offers a blueprint for regenerative farming, reducing reliance on synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, improving soil health, and conserving water.

- Biodiversity Conservation: Revitalizing traditional seed saving practices is crucial for preserving genetic diversity and building resilient food systems in the face of climate change.

- Food Security and Sovereignty: Many Native American communities are actively working to reclaim their agricultural heritage, establish community gardens, and restore traditional foodways to combat diet-related diseases and achieve greater food independence.

- Climate Change Adaptation: The inherent resilience and adaptability of Indigenous farming systems offer valuable lessons for developing climate-smart agricultural strategies.

The story of Native American agriculture, particularly the Three Sisters, is a powerful reminder that humanity has long possessed the knowledge to live in harmony with the earth. It is a legacy of innovation, deep ecological understanding, and spiritual connection that offers not just a glimpse into the past, but a guiding light for a more sustainable and equitable future. As we grapple with environmental degradation and food system crises, the ancient wisdom embedded in these fields continues to whisper profound truths about interdependence, gratitude, and the enduring power of a symphony in the soil.