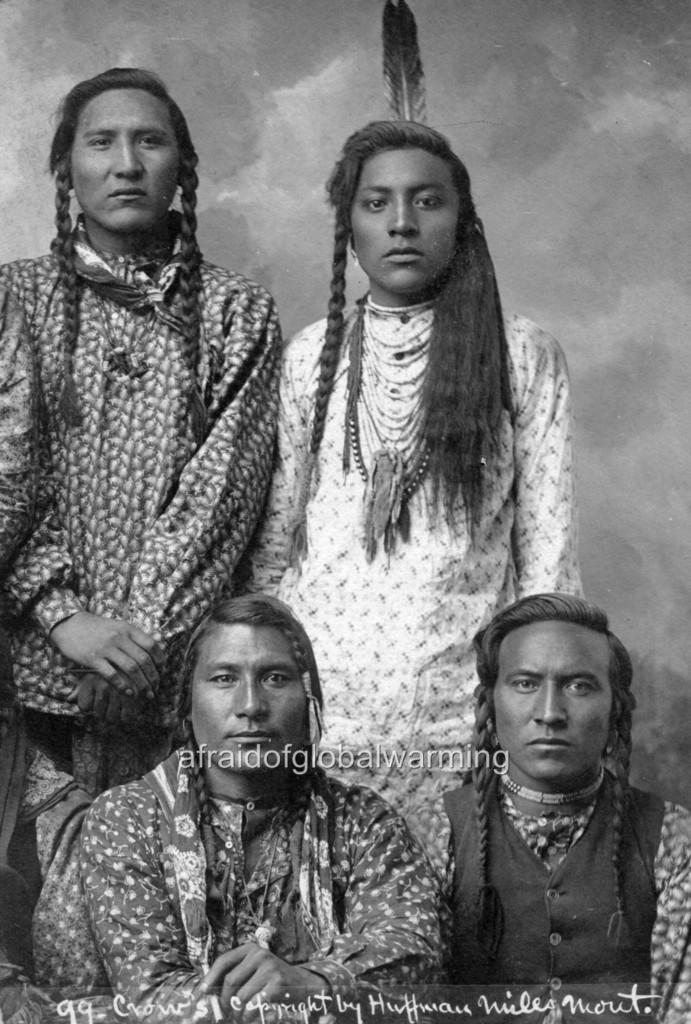

Montana’s Enduring Apsáalooke: Guardians of Plains Culture and Resilience

In the vast, undulating landscapes of southeastern Montana, where the Bighorn Mountains rise majestically from the plains and the Yellowstone River carves its ancient path, lives a people whose history is as interwoven with the land as the threads of their intricate beadwork. They are the Apsáalooke, known to the world as the Crow Tribe, a vibrant and resilient nation whose cultural heritage, deeply rooted in the Northern Plains, continues to thrive despite centuries of dramatic change. Their story is not merely one of survival, but of profound adaptation, strategic diplomacy, and an unwavering commitment to their unique identity.

The name "Apsáalooke" itself is a testament to their distinctiveness. It translates to "Children of the Large-Beaked Bird," often interpreted as a large bird like a raven or crow, leading to the common English designation. This name, steeped in their oral traditions, reflects a deep spiritual connection to the natural world and a self-perception as people of the air and the land. Their ancestral territory was once immense, stretching across parts of Montana, Wyoming, and North Dakota, encompassing a diverse array of ecosystems that provided abundant resources and spiritual solace.

The Golden Age of the Horse and Buffalo

Before the arrival of European settlers, the Apsáalooke were masters of the Northern Plains. Their culture reached its zenith with the adoption of the horse, a transformative event that redefined their way of life. The Crow quickly became renowned as among the finest horsemen and horse breeders on the plains. Horses were not merely tools; they were wealth, status symbols, and companions, central to hunting, warfare, and ceremonial life. A family’s prestige was often measured by the size and quality of their horse herd.

The horse, coupled with their intimate knowledge of the land, allowed the Apsáalooke to effectively hunt the vast buffalo herds that roamed the plains. The buffalo, or bison, was the cornerstone of their existence, providing sustenance, shelter, clothing, tools, and spiritual significance. Every part of the animal was utilized, embodying a philosophy of respect and resourcefulness. Their nomadic lifestyle, following the buffalo herds, saw them living in elegant, painted tipis – easily transportable and remarkably well-suited to the harsh plains environment. These tipis were often adorned with elaborate designs, reflecting the artistic prowess and spiritual beliefs of their inhabitants.

Apsáalooke society was characterized by a complex social structure, including clans (organized through the mother’s side, highlighting the importance of women in their society) and prestigious warrior societies like the Big Dogs and the Lumpwoods. These societies were crucial for defense, hunting coordination, and maintaining social order. Spiritual life was rich and pervasive, with ceremonies such as the Sun Dance serving as powerful expressions of communal identity, sacrifice, and renewal. Vision quests, often undertaken in the solitude of the Bighorn Mountains, connected individuals to the spiritual realm and provided guidance for their lives.

Navigating a Changing World: Treaties, Conflicts, and Strategic Alliances

The 19th century brought an era of immense upheaval to the Apsáalooke. As European American expansion pushed westward, competition for land and resources intensified. The Crow found themselves caught between the encroaching United States government and their traditional enemies, primarily the Sioux (Lakota and Dakota) and Cheyenne, who were also being displaced and pushed into Crow territory.

In 1851, the Crow were signatories to the first Fort Laramie Treaty, which recognized their claim to a vast territory of approximately 38 million acres. However, this land base was significantly reduced in subsequent treaties, particularly the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty, which established the Crow Indian Reservation in its current form, albeit still a considerable 2.2 million acres. This reduction was a bitter pill, but the Crow, under astute leadership, often chose diplomacy and strategic alliance over outright confrontation with the US military, a decision that proved crucial for their survival as a distinct nation.

Perhaps one of the most intriguing and often misunderstood aspects of Crow history is their role as scouts for the U.S. Army. Unlike many other tribes, the Apsáalooke allied themselves with the Americans against their long-standing adversaries. This was not an act of betrayal against Native American solidarity, but a calculated strategy to protect their remaining lands and people from the aggressive incursions of the Sioux and Cheyenne. Crow scouts played a significant role in several campaigns, including the infamous Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876. While often overshadowed by the narratives of Custer and the Sioux, Crow scouts like Curley, White Man Runs Him, Hairy Moccasin, Goes Ahead, and Half Yellow Face provided invaluable intelligence and often found themselves in the thick of the fighting. Their participation underscores the complex, multi-faceted nature of frontier warfare and the desperate choices tribes faced.

Resilience in the Face of Assimilation

The reservation era, beginning in the late 19th century, presented new and formidable challenges. The buffalo herds were decimated, the nomadic way of life was curtailed, and federal policies actively sought to dismantle Native American cultures through forced assimilation. Children were sent to boarding schools, where their language, traditions, and spiritual practices were suppressed. The communal land base was threatened by the Dawes Act, which sought to divide tribal lands into individual allotments.

Yet, the Apsáalooke demonstrated an extraordinary capacity for resilience. Leaders like Chief Plenty Coups (Alaxchiiaahush), the last traditional principal chief of the Crow, epitomized this spirit. Plenty Coups famously had a vision as a young man that foretold the disappearance of the buffalo and the need for his people to adapt. His leadership guided the Crow through this tumultuous period, emphasizing the importance of education and diplomacy. He once stated, "Education is your greatest weapon. With it, you are the white man’s equal; without it, you are his victim." His journey to Washington D.C. and his presence at the dedication of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in 1921, representing all Native Americans, solidified his legacy as a statesman and a visionary.

The Crow Nation Today: A Living Culture

Today, the Crow Tribe, officially known as the Crow Nation, remains a vibrant and self-governing entity with its capital in Crow Agency, Montana. Their reservation is the largest in Montana and the seventh largest in the United States, a testament to their historical tenacity in preserving their land base. The Crow Tribal Council governs the nation, overseeing a wide range of services for its approximately 12,000 enrolled members.

Cultural preservation is a paramount concern. Efforts are underway to revitalize the Apsáalooke language, a distinct Siouan language, through immersion programs and educational initiatives. Traditional arts, such as beadwork, quillwork, and parfleche painting, continue to be practiced and celebrated, often passed down through generations. The Sun Dance, a deeply sacred ceremony, continues to be performed, maintaining a vital connection to their spiritual heritage.

Perhaps the most visible and celebrated manifestation of Crow culture today is the annual Crow Fair, held every August near Crow Agency. Known as "the Teepee Capital of the World," Crow Fair is one of the largest and most prestigious Native American gatherings in the country. Thousands of tipis dot the landscape, and attendees from across the globe come to witness the spectacle of powwows, rodeos, horse racing, and parades. It is a powerful affirmation of Apsáalooke identity, a joyous celebration of their past, present, and future, and a testament to their unbroken cultural chain.

Economically, the Crow Nation faces both opportunities and challenges. The reservation possesses significant natural resources, including coal, which offers potential for development. However, balancing resource extraction with environmental stewardship and sustainable economic growth remains a complex task. Agriculture and ranching continue to be important sectors, alongside growing efforts in tourism and small business development.

The Apsáalooke also play a crucial role in broader Montana society, contributing to the state’s cultural tapestry and economy. They are stewards of a vast and ecologically significant landscape, and their traditional ecological knowledge is invaluable in addressing contemporary environmental challenges.

In conclusion, the Crow Tribe of Montana, the Apsáalooke, stands as a powerful symbol of Indigenous resilience and cultural continuity. From their ancient origins as "Children of the Large-Beaked Bird" to their strategic adaptation during the tumultuous frontier era, and their enduring commitment to tradition in the modern world, their story is one of unwavering spirit. They are not a relic of the past, but a living, breathing nation, actively shaping their future while holding fast to the profound cultural heritage that defines them. Their mountains, their rivers, and their plains whisper tales of ancestors, warriors, and visionaries, reminding us that the Apsáalooke are, and always will be, the guardians of their unique and vibrant plains culture.