Echoes of Manoomin: The Enduring Language, Traditions, and Great Lakes Heritage of the Ojibwe People

The vast, shimmering expanse of the Great Lakes has long been more than just a geographical feature; for the Ojibwe people, it is the sacred cradle of their civilization, a source of sustenance, and the very foundation of their identity. Known to themselves as Anishinaabeg – "the good humans" or "the original people" – the Ojibwe (also frequently referred to as Chippewa, a colonial mispronunciation of their name) are one of North America’s largest and most geographically widespread Indigenous nations. Their history, language, and intricate traditions are deeply interwoven with the waters, forests, and spirit of the Great Lakes region, a heritage they have fiercely protected and continuously revitalize despite centuries of colonial pressures.

The Anishinaabeg and Their Homeland

The Anishinaabeg confederacy, often called the "People of the Three Fires," comprises the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi nations, bound by kinship, language, and a shared spiritual journey. Oral histories recount their ancient migration from the Eastern Seaboard, following a prophecy that guided them westward to where "food grows on water." This prophecy led them to Manoomin, or wild rice (Zizania aquatica), which flourished in the shallow, clear waters of the Great Lakes and became a foundational food source and a sacred gift. This journey solidified their spiritual connection to the land stretching across what is now Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, North Dakota, and Montana.

For the Ojibwe, the Great Lakes are not merely a resource but a living entity, imbued with spirits and stories. Lake Superior, or Gichigami ("great sea"), holds particular reverence, its depths and shores home to ancient tales and sacred sites. This profound relationship with their environment shaped every aspect of their culture, from their sustainable hunting and harvesting practices to their architectural ingenuity, such as the construction of wiigwaam (birch bark homes) and the legendary birch bark canoes, masterpieces of engineering that allowed for efficient travel across the interconnected waterways.

Anishinaabemowin: The Living Heart of Culture

At the very core of Ojibwe identity is Anishinaabemowin, their ancestral language. More than just a means of communication, the language is a repository of their worldview, spiritual beliefs, and intricate understanding of the natural world. It is a highly descriptive, verb-based language that emphasizes processes, relationships, and the animate nature of the world. For instance, while English might describe a "bay," Anishinaabemowin would use a phrase like "the place where the water curves in," reflecting a dynamic and relational understanding.

However, Anishinaabemowin, like many Indigenous languages, faces significant threats. Centuries of assimilationist policies, most notably the residential school system in Canada and boarding schools in the U.S., actively suppressed the use of Indigenous languages, punishing children for speaking their mother tongue. This deliberate and brutal assault on cultural identity led to a dramatic decline in fluent speakers. Today, while exact numbers vary, estimates suggest there are tens of thousands of Ojibwe people, but only a small percentage are fluent speakers, predominantly elders.

Yet, there is a powerful and growing movement to revitalize Anishinaabemowin. Communities are creating immersion schools, language camps, and digital resources to teach the language to younger generations. The Waadookodaading Ojibwe Language Immersion School in Hayward, Wisconsin, is a beacon of this effort, where all subjects are taught in Anishinaabemowin from kindergarten through high school, aiming to raise a new generation of fluent speakers. "When we speak our language, we are not just using words; we are speaking the minds of our ancestors, feeling the spirit of our land, and breathing life into our future," explains an elder involved in language revitalization efforts. These initiatives are not just about preserving words; they are about reclaiming cultural sovereignty, healing historical trauma, and ensuring the continuity of Anishinaabe knowledge.

Traditions: Weaving the Fabric of Life

Ojibwe traditions are rich, diverse, and deeply rooted in spiritual principles that emphasize interconnectedness, respect, and balance. Central to their ethical framework are the Seven Grandfather Teachings: Zaagi’idiwin (Love), Debwewin (Truth), Mnaadendimoowin (Respect), Aakode’ewin (Bravery), Gwayakwaadiziwin (Honesty), Dabasendizowin (Humility), and Nbwaakaawin (Wisdom). These teachings are often conveyed through stories and ceremonies, guiding individuals on their path to living a good life and contributing positively to their community.

Storytelling, especially during the long winter months, is a vital tradition. Elders are the keepers of these oral histories, myths, legends, and teachings, which transmit cultural knowledge, moral lessons, and historical events across generations. Stories like that of Nanabush, the trickster-hero, not only entertain but also impart profound insights into human nature and the spiritual world.

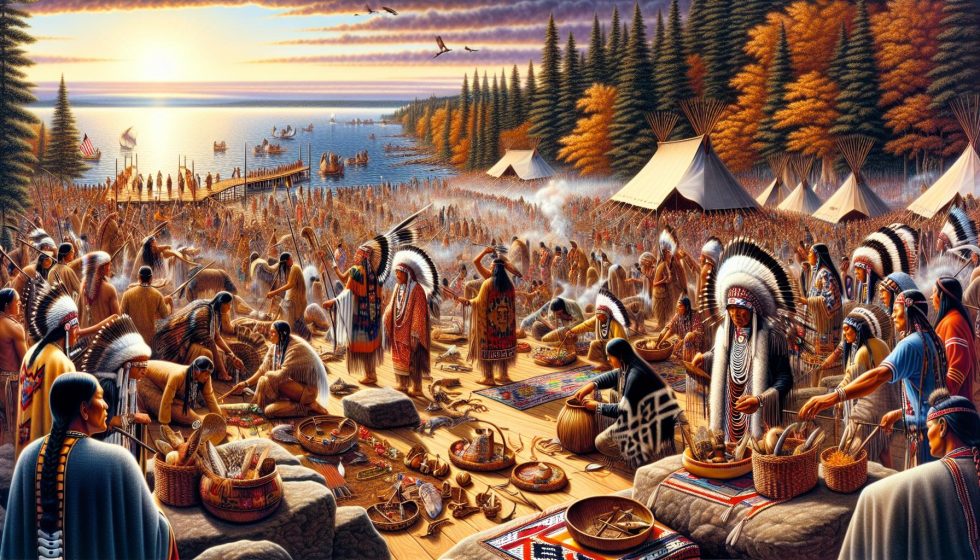

Ceremonies also play a crucial role. The Wiikondi (Powwow) is a vibrant public celebration of dance, song, and community, a testament to the enduring spirit of Indigenous peoples. More private ceremonies, such as the Madoodiswan (Sweat Lodge), offer spiritual purification and connection to the Creator. The Vision Quest, a solitary journey into the wilderness, allows individuals to seek spiritual guidance and discover their purpose. The Midewiwin (Grand Medicine Society) is another significant spiritual institution, preserving ancient knowledge, healing practices, and ceremonial protocols.

Art, Craft, and Sustenance: Expressions of Heritage

The Ojibwe people are renowned for their intricate artistry and craftsmanship, which are not merely decorative but deeply meaningful. Floral motifs, often rendered in beadwork, quillwork, and appliqué, are characteristic of Ojibwe art. These designs reflect their profound appreciation for the natural beauty of their environment, drawing inspiration from the plants and flowers that populate their homelands. Each stitch and quill tells a story, connecting the wearer or owner to their identity and the spirit world.

Beyond aesthetics, traditional crafts were essential for survival. The making of birch bark containers (makakoon) for storing maple sugar (ziinzibaakwad) or berries, or the weaving of cattail mats for shelter, all demonstrate an ingenious understanding of local resources and sustainable practices. The annual harvesting of Manoomin (wild rice) remains a sacred tradition, a communal effort that reinforces their connection to the land and each other. Maple sugar camps in early spring, fishing with nets and spears, and hunting for deer and moose were all highly skilled activities passed down through generations, ensuring the community’s well-being while maintaining respect for the spirit of the animals.

Resilience, Challenges, and the Path Forward

The history of the Ojibwe people, like that of many Indigenous nations, is marked by immense challenges. The arrival of European colonizers brought disease, forced displacement, and a relentless assault on their cultural practices and sovereignty. Treaties, often violated or misinterpreted by colonial governments, led to significant land loss and the erosion of traditional governance structures. The aforementioned residential and boarding school systems inflicted intergenerational trauma, severing children from their families, languages, and cultures.

Despite these adversities, the Ojibwe people have demonstrated extraordinary resilience. They have fought tirelessly to protect their treaty rights, land, and water. Legal battles have affirmed their inherent rights to hunt, fish, and gather on ceded territories, often facing resistance and racism. The ongoing struggle for self-determination and sovereignty continues, with communities working to rebuild their nations, strengthen their economies, and assert their rightful place in the modern world.

Today, the Ojibwe people are a vibrant and diverse nation, with communities thriving across the Great Lakes region and beyond. They are leaders in environmental stewardship, advocating for the protection of water and land that has sustained them for millennia. They are educators, artists, politicians, and healers, bringing their unique perspectives and wisdom to contemporary issues.

The echoes of Manoomin continue to resonate across the Great Lakes. The enduring language, the rich tapestry of traditions, and the unbreakable spirit of the Anishinaabeg serve as a powerful testament to their profound heritage. Their journey is a continuous affirmation of identity, a reclamation of voice, and a testament to the enduring power of culture in the face of adversity, offering invaluable lessons to the world about interconnectedness, respect, and the profound wisdom embedded in living harmoniously with the land. As the elders say, "We are still here. Our language is still here. Our stories are still here. And we will continue to share them."