Guardians of the Plateau: The Enduring Legacy of the Cayuse Tribe

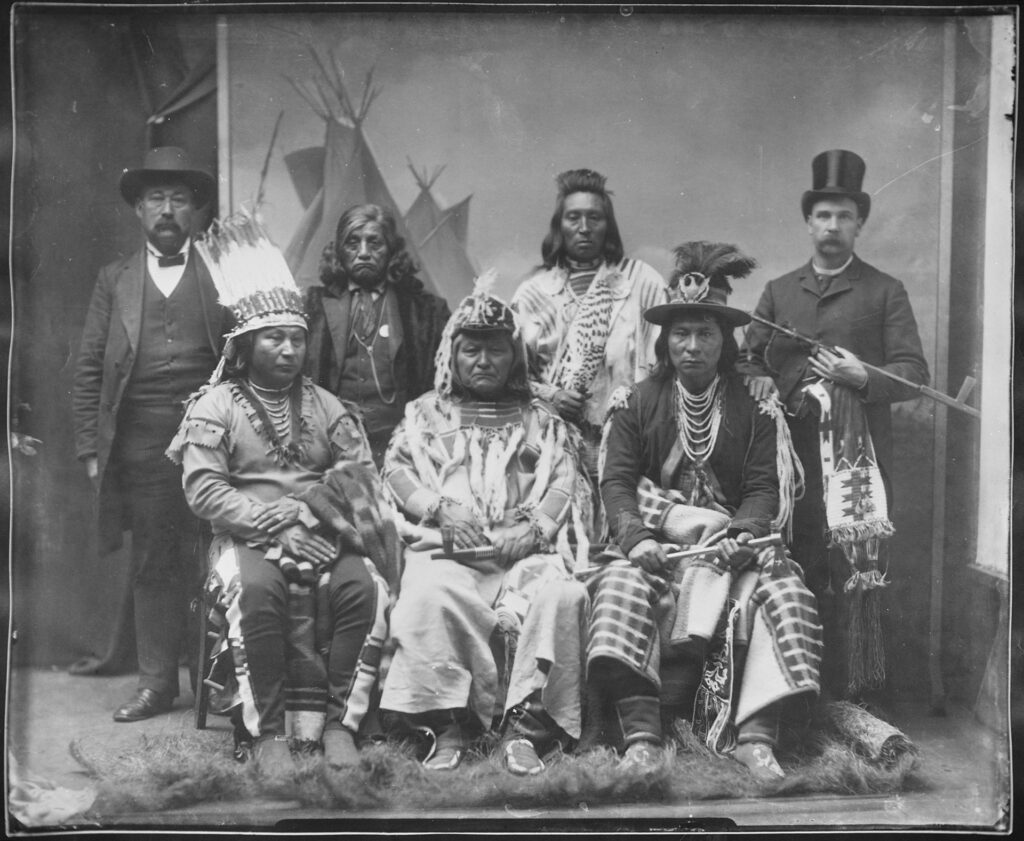

Oregon’s landscapes tell stories etched in ancient rock, carved by mighty rivers, and whispered through the rustling leaves of its forests. Among these narratives, few are as profound and complex as that of the Cayuse Tribe. For millennia, the Cayuse, a vibrant and resourceful people, thrived on the Columbia River Plateau, their lives intricately woven with the rhythms of the land. Their history is a testament to resilience, a poignant chronicle of cultural richness, devastating conflict, and an enduring spirit that continues to shape the identity of their descendants today.

To understand the Cayuse is to first understand their ancestral home. The Columbia Plateau, a vast and diverse region encompassing parts of present-day Oregon, Washington, and Idaho, was a land of abundance. Here, the Cayuse, speakers of a Sahaptian language related to that of the Nez Perce and Walla Walla, developed a sophisticated semi-nomadic lifestyle. Their annual cycle was a carefully orchestrated migration, following the seasonal availability of resources. Spring brought them to the rivers for the vital salmon runs, a spiritual and dietary cornerstone. Summer saw them move to verdant valleys and mountain meadows, gathering camas roots, berries, and other plant foods. Autumn was dedicated to hunting deer, elk, and bison on the plains, and preparing for the lean months of winter, which they spent in semi-subterranean lodges.

A pivotal moment in Cayuse history, long before the arrival of Europeans, was the introduction of the horse, likely in the early 18th century. This majestic animal, which came to define their culture, revolutionized their way of life. The Cayuse quickly became renowned horse breeders and riders, developing a distinct and highly prized breed known as the "Cayuse pony." The horse provided unparalleled mobility, transforming hunting practices, expanding trade networks across the Plateau and beyond, and dramatically increasing their military prowess. Wealth was measured in horses, and their equestrian skills became legendary, fostering a proud and independent spirit. As one tribal elder might have reflected, "The horse was our wings, our swift legs, carrying us to the bounty of the land and across great distances to our kin."

The relative isolation of the Plateau began to erode in the early 19th century with the arrival of Euro-American explorers and fur traders. Lewis and Clark, passing through Cayuse territory in 1805, were among the first to document encounters, noting the Cayuse’s impressive horsemanship and their sophisticated trading practices. These initial interactions, while often cordial, marked the beginning of a profound cultural collision. The Cayuse, like many Indigenous peoples, initially engaged in trade, exchanging furs and horses for metal tools, firearms, and other goods that seemed advantageous. However, these exchanges also brought insidious threats: new diseases against which they had no immunity, and an escalating demand for land and resources.

The true turning point arrived with the missionaries. In 1836, Marcus and Narcissa Whitman, sent by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, established a mission at Waiilatpu, near present-day Walla Walla, Washington, deep within Cayuse territory. Their goal was not merely to convert the Cayuse to Christianity but also to "civilize" them – to transform them into sedentary farmers, abandoning their traditional ways. While some Cayuse were curious and sought knowledge, many viewed the missionaries with growing suspicion. The Whitmans’ insistence on land ownership, their cultural insensitivity, and their perceived lack of respect for Cayuse spiritual practices created a deep chasm of misunderstanding.

The tension reached a tragic crescendo in 1847. A devastating measles epidemic, brought by white settlers traveling the Oregon Trail, swept through the Plateau, decimating the Cayuse population. The Cayuse, unfamiliar with the disease, watched in horror as their people died by the hundreds, while many white settlers, seemingly more resistant, recovered. In their traditional belief system, a medicine person who failed to cure was considered a malevolent force, often held responsible for the illness. Marcus Whitman, as the primary healer in the community, became the focus of their grief, anger, and desperation.

On November 29, 1847, a group of Cayuse attacked the mission, killing Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and eleven others. This event, known as the Whitman Massacre, became a flashpoint in Oregon history, igniting the Cayuse War (1847-1850). The massacre, while a horrific tragedy, was a desperate act fueled by fear, disease, and a profound cultural chasm, rather than simple savagery. It plunged the region into years of conflict, leading to further loss of life and the systematic dispossession of Cayuse lands. The incident was exploited by American settlers to justify aggressive expansion and military campaigns against Indigenous peoples throughout the Pacific Northwest.

The aftermath of the Cayuse War was devastating. The tribe was effectively broken, their numbers reduced, and their autonomy severely curtailed. In 1855, along with the Umatilla and Walla Walla tribes, the Cayuse were forced to sign the Treaty of Walla Walla. This treaty, one of the most significant in the region, ceded millions of acres of ancestral lands to the United States, reserving a much smaller tract for the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation (CTUIR) in northeastern Oregon. The reservation became a crucible where the three distinct tribes, bound by shared experience and a common future, began to forge a new identity.

The reservation era was marked by immense hardship. Government policies aimed at forced assimilation sought to eradicate Indigenous languages, spiritual practices, and traditional governance. Children were sent to boarding schools, where they were forbidden to speak their native tongues and punished for practicing their culture. Economic opportunities were scarce, and poverty became rampant. Yet, despite these relentless pressures, the spirit of the Cayuse, Umatilla, and Walla Walla peoples endured. They held onto their traditions in secret, passing down stories, songs, and knowledge from generation to generation, often at great personal risk.

The mid-20th century brought a slow but steady movement towards self-determination. Beginning in the 1970s, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation began to reclaim their sovereignty and assert control over their own affairs. This era saw a resurgence of cultural pride and a commitment to revitalizing language, ceremonies, and traditional arts. Elders, who had carefully guarded the old ways, became invaluable teachers, guiding younger generations in the path of their ancestors.

Today, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation (CTUIR) stands as a powerful example of Indigenous self-governance and resilience. The Cayuse, as one of the three confederated tribes, play an integral role in this vibrant modern nation. The CTUIR operates a sophisticated government, managing its own police force, judicial system, and public services for its members. Economically, the Tribes have diversified, with enterprises ranging from gaming (Wildhorse Resort & Casino) and agriculture to natural resource management and renewable energy. These ventures not only provide employment and revenue but also fund essential tribal programs in education, healthcare, and cultural preservation.

Cultural revitalization remains a cornerstone of the CTUIR’s mission. The Tamástslikt Cultural Institute serves as a world-class museum and interpretive center, telling the story of the Cayuse, Umatilla, and Walla Walla peoples from their own perspectives. Language programs are actively working to preserve and teach Sahaptian, ensuring that the voices of their ancestors continue to echo through future generations. Traditional ceremonies, such as the Root Feast and the Salmon Ceremony, are celebrated with renewed vigor, connecting tribal members to their spiritual heritage and the bounty of the land and rivers.

The Cayuse people’s journey from the expansive Plateau to the modern era is a profound narrative of survival, adaptation, and an unwavering commitment to identity. They faced disease, war, dispossession, and systematic attempts at cultural annihilation, yet they never surrendered their spirit. Their history serves as a vital reminder of the strength of Indigenous cultures and the devastating consequences of colonial expansion. As guardians of the Plateau, the Cayuse, through the CTUIR, continue to advocate for tribal sovereignty, protect their treaty rights, and work tirelessly to ensure that their rich legacy, once nearly extinguished, shines brightly for generations to come. Their story is not just a chapter in Oregon’s past; it is a living, breathing testament to an enduring people, forever woven into the fabric of the Pacific Northwest.