Okay, here is a 1200-word journalistic article in English on the history of Native American social justice, incorporating facts and a quote.

Echoes of Injustice, Voices of Resilience: The Enduring Struggle for Native American Social Justice

The story of Native American social justice is not a singular narrative but a complex tapestry woven from centuries of resistance, resilience, and an unwavering fight for self-determination. It is a history marked by broken treaties, forced assimilation, and systemic discrimination, yet equally defined by powerful movements, cultural revitalization, and an enduring spirit that continues to shape the landscape of human rights and sovereignty in the United States. To understand this ongoing struggle is to confront the foundational injustices upon which a nation was built and to acknowledge the vibrant, diverse cultures that have persisted against overwhelming odds.

The roots of this struggle predate the formation of the United States, stretching back to the earliest encounters between Indigenous peoples and European colonizers. For millennia, Native American nations thrived, each with distinct languages, governance structures, spiritual beliefs, and sophisticated societies. The arrival of Europeans, however, ushered in an era of devastating demographic collapse due to disease, followed by relentless land dispossession, resource exploitation, and the imposition of foreign legal and social systems. Early colonial policies, often cloaked in rhetoric of "discovery" and "civilization," laid the groundwork for centuries of injustice.

With the birth of the United States, these injustices were codified. The U.S. Constitution, while acknowledging treaties, often treated Native nations as foreign entities subject to federal power, not as sovereign equals. The 19th century became a particularly dark chapter. The Indian Removal Act of 1830, championed by President Andrew Jackson, authorized the forced displacement of thousands of Indigenous peoples from their ancestral lands in the southeastern United States to Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River. This brutal migration, epitomized by the Cherokee Nation’s "Trail of Tears," resulted in the deaths of thousands from disease, starvation, and exposure. As Cherokee leader John Ross famously stated in an 1836 address to the U.S. Senate, "The fully executed treaty of New Echota has been obtained by fraud and is a mere nullity." While his efforts, and those of his people, were ultimately unsuccessful in preventing the removal, his words underscore the deep sense of betrayal and the early, articulate calls for justice.

Following the removals, the U.S. government shifted its policy towards "assimilation." The Dawes Allotment Act of 1887 was perhaps the most destructive legislative attempt at this. It aimed to break up communally held tribal lands into individual plots, ostensibly to encourage farming and integrate Native Americans into mainstream American society. The surplus land, however, was then sold off to non-Native settlers, resulting in the loss of nearly two-thirds of the remaining Native land base – from 138 million acres in 1887 to just 48 million by 1934. This policy not only dispossessed tribes of vast territories but also severely undermined their social structures and economic viability.

Concurrent with allotment were the infamous Indian boarding schools. Institutions like the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, founded in 1879, operated under the chilling motto, "Kill the Indian, Save the Man." Native children, often forcibly removed from their families, were stripped of their traditional clothing, forbidden to speak their languages, and punished for practicing their cultural customs. The goal was cultural genocide, severing children from their heritage to mold them into subservient, "civilized" Americans. The psychological, emotional, and spiritual trauma inflicted by these schools continues to reverberate through generations, contributing to intergenerational trauma and a profound sense of loss.

The early 20th century saw the beginnings of a shift. The Meriam Report of 1928, commissioned by the U.S. government, was a scathing indictment of federal Indian policy, exposing the dire poverty, poor health, and inadequate education suffered by Native Americans. Its findings paved the way for the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934, which aimed to reverse the Dawes Act, promote tribal self-governance, and revitalize Native cultures. While the IRA was a step towards self-determination, its implementation was often flawed, imposing foreign governmental structures on tribes and still operating under federal oversight.

The post-World War II era brought a new wave of federal policies designed to terminate the federal government’s trust relationship with tribes and relocate Native Americans to urban centers. "Termination" policies, enacted in the 1950s and early 1960s, sought to dissolve tribal governments, eliminate federal services, and subject Native lands to state jurisdiction. The Menominee Nation of Wisconsin, for example, lost its federal recognition in 1961, leading to economic collapse and severe social dislocation, a fate shared by over 100 other tribes. The "Relocation" program encouraged Native Americans to leave reservations for cities, promising jobs and opportunities that rarely materialized, leading to further cultural disruption and the creation of urban Native American communities struggling with poverty and discrimination.

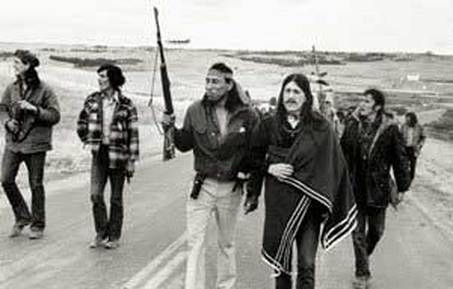

These destructive policies, however, fueled a powerful resurgence of Native American activism. Inspired by the Civil Rights Movement, the "Red Power" movement of the 1960s and 70s galvanized Indigenous peoples across the continent. Groups like the American Indian Movement (AIM), founded in 1968, brought national and international attention to Native American issues through direct action and protests. The occupation of Alcatraz Island from 1969 to 1971 by "Indians of All Tribes" demanded the return of federal lands to Native control, citing an 1868 Sioux treaty. The 1972 Trail of Broken Treaties march on Washington D.C. culminated in the occupation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs building, highlighting historical grievances and demanding treaty enforcement. The 1973 standoff at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, between AIM activists and federal agents, though violent, dramatically underscored the ongoing struggle for sovereignty and justice.

These movements were pivotal in shifting federal policy towards "self-determination." The Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 allowed tribes to take greater control over federal programs and services designed for their communities, marking a significant move away from paternalistic federal oversight. This era also saw the rise of tribal gaming as a means of economic development, with the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act of 1988 providing a framework for tribes to operate casinos on their lands. While controversial, gaming has provided many tribes with unprecedented resources to fund essential services, education, and infrastructure, fostering a new level of economic sovereignty.

Yet, the fight for social justice is far from over. Contemporary issues include the ongoing struggle for land back, the protection of sacred sites, and environmental justice. The Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) protests at Standing Rock, North Dakota, in 2016-2017, saw thousands of "water protectors" from across the globe converge to oppose the pipeline’s construction through sacred lands and under a vital water source, highlighting the intersection of Indigenous rights and environmental protection.

Perhaps one of the most pressing contemporary issues is the crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-Spirit people (MMIWG2S). Indigenous women face alarmingly high rates of violence, with murder rates ten times the national average on some reservations. Systemic issues like jurisdictional complexities, inadequate law enforcement resources, and a lack of data have contributed to this devastating crisis. The MMIWG2S movement has brought critical awareness to these injustices, demanding federal and state action to protect Indigenous lives and bring perpetrators to justice.

Beyond these high-profile struggles, Native American communities continue to advocate for equitable access to healthcare, education, and housing. They fight against cultural appropriation, for the protection of intellectual property, and for the respectful representation of their histories and cultures. The revitalization of Indigenous languages, the return of ancestral remains, and the ongoing efforts to heal historical trauma are all integral parts of the contemporary social justice movement.

In conclusion, the history of Native American social justice is a testament to extraordinary resilience in the face of relentless oppression. From the earliest resistance to colonization to the modern-day fights for environmental justice and the MMIWG2S movement, Indigenous peoples have consistently asserted their inherent sovereignty, cultural integrity, and human rights. While significant strides have been made, the path to true justice is long and requires continued awareness, allyship, and a deep commitment to rectifying historical wrongs and supporting the self-determination of Native nations. The echoes of injustice still resonate, but the voices of resilience are growing louder, demanding a future where Indigenous peoples not only survive but thrive on their own terms.