The Unseen Tapestry: Native American Contributions to Modern Art

When the story of modern art is told, it often begins in the bustling ateliers of Paris, tracing a lineage from Impressionism through Cubism, Surrealism, and Abstract Expressionism, primarily through a Eurocentric lens. Yet, beneath the familiar narratives, an enduring, often unacknowledged current has flowed from the diverse artistic traditions of Native American cultures, enriching, challenging, and profoundly shaping the very fabric of what we call modern art. Far from being relegated to ethnographic museums or historical footnotes, Indigenous artistic principles, philosophies, and aesthetics have woven an unseen tapestry that continues to influence contemporary practice, challenging the boundaries of art itself.

For centuries, before the arrival of European settlers, Indigenous peoples across North America cultivated vibrant, sophisticated artistic traditions. These were not merely decorative; they were integral to spiritual life, social structure, historical record-keeping, and the very act of being. From the intricate pottery of the Pueblo peoples and the dynamic basketry of the Pomo to the monumental totem poles of the Pacific Northwest and the ephemeral sand paintings of the Navajo, art served a purpose far beyond aesthetics. It was, as many Indigenous scholars and artists affirm, life itself.

This fundamental difference in artistic philosophy is perhaps the first, and most profound, contribution. Western art, particularly after the Renaissance, increasingly emphasized individual genius, the separation of art from craft, and the pursuit of beauty for its own sake. Indigenous art, conversely, rarely drew such distinctions. A beautifully woven blanket was not merely a textile; it was a narrative, a prayer, a symbol of community and connection to the land. A painted hide was not just a canvas; it was a historical document and a spiritual guide. This holistic worldview, where art, life, and spirit are indivisible, offered a radical alternative to the emerging modern art movements seeking to break free from traditional constraints.

The early 20th century saw a burgeoning interest in "primitivism" among European avant-garde artists. While this often involved the problematic appropriation of African and Oceanic art, it nonetheless opened a crucial door: the recognition that non-Western art held a power and sophistication previously dismissed. Artists like Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, searching for new forms of expression, found inspiration in the raw energy and abstract qualities of masks and sculptures from other cultures. While direct influence from Native American art on these earliest modernists is less documented than from African art, the broader shift in perspective — away from academic realism towards symbolic, spiritual, and abstracted forms — created a fertile ground for later appreciation of Indigenous aesthetics.

It was in the American Southwest, however, that Native American art began to exert a more direct and palpable influence on modern art. The stark landscapes and vibrant cultures of the Pueblo, Navajo, and Apache peoples drew artists and writers from the East, seeking authenticity and a connection to a seemingly more ancient way of life. Georgia O’Keeffe, for instance, famously captivated by the desert, incorporated the bleached bones, stark lines, and spiritual resonance of the landscape into her iconic paintings. Her work, while distinctly her own, echoed the profound connection to place that defines much of Native American art. She was part of a larger movement of artists who, consciously or unconsciously, absorbed the visual language and spiritual depth of the region’s Indigenous inhabitants.

Perhaps one of the most debated, yet compelling, instances of Native American influence lies within Abstract Expressionism, particularly in the work of Jackson Pollock. Pollock’s revolutionary "drip" paintings, with their energetic, all-over compositions and emphasis on process, bear striking resemblances to the sand paintings of the Navajo (Diné) people. Navajo sand paintings, created during healing ceremonies, are ephemeral artworks made by sprinkling colored sands onto a ground surface. They are not meant to be preserved but are powerful, ritualistic acts, deeply connected to spirituality and the natural world.

While Pollock himself never explicitly acknowledged a direct influence from Navajo sand painting, art historian W. Jackson Rushing III has extensively explored the parallels. Rushing points out that Pollock was exposed to Navajo sand painting demonstrations in the 1940s and that the emphasis on working on the floor, the use of continuous lines, and the performative aspect of creating the work resonate deeply with Indigenous practices. As Rushing notes in "Native American Art and the New York Avant-Garde," "Pollock’s work, though secular in intent, shares a common ground with Navajo painting in its emphasis on process, its non-hierarchical composition, and its connection to the earth." The very act of creation became a ritual, blurring the lines between artist, artwork, and environment—a concept deeply embedded in Native American art forms for millennia.

Beyond the formal aesthetics, Native American philosophies of land, time, and environment have also profoundly influenced movements like Land Art or Earth Art. Artists such as Robert Smithson, known for his monumental "Spiral Jetty" (1970) in the Great Salt Lake, engaged directly with natural landscapes, transforming them into site-specific sculptures. While Smithson’s work emerged from a Western conceptual framework, it inadvertently echoed Indigenous traditions of land modification and sacred sites—from effigy mounds to medicine wheels—that have existed for thousands of years. These ancient sites demonstrate a profound understanding of ecological systems, astronomical alignments, and a desire to communicate with the land rather than simply dominate it. The concept of art as an integral part of the environment, rather than an object separated from it, found a powerful resonance in these modern movements.

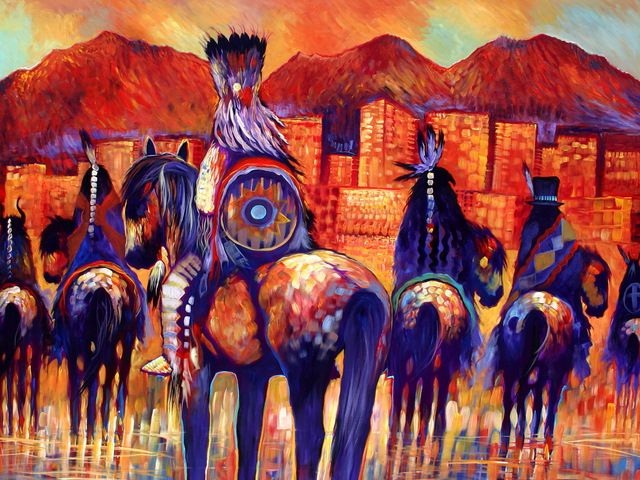

In the latter half of the 20th century and into the 21st, Native American artists themselves stepped forward to reclaim their narratives and contribute directly to the discourse of modern and contemporary art. No longer content to be viewed solely through an anthropological lens, artists like Fritz Scholder (Luiseño), T.C. Cannon (Kiowa/Caddo), and Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (Salish/Kootenai) challenged stereotypes and infused traditional Indigenous motifs with modern techniques and critical commentary.

Fritz Scholder, a pivotal figure, famously declared, "I am not an Indian artist, I am an artist who happens to be Indian." His bold, expressive paintings of Native Americans, often depicted with a sense of alienation or irony, shattered romanticized notions and injected a raw, contemporary edge into Indigenous portraiture. Similarly, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith utilizes abstraction and collage to critique colonial narratives, environmental destruction, and the commodification of Native culture. Her work, often layered with newspaper clippings, maps, and symbolic imagery, confronts viewers with the ongoing realities of Indigenous existence while simultaneously celebrating resilience.

Contemporary Native American artists continue to push boundaries, blending ancestral knowledge with cutting-edge techniques and global perspectives. Jeffrey Gibson (Choctaw/Cherokee), for example, creates vibrant, multi-media installations and sculptures that fuse traditional beadwork, quillwork, and parfleche designs with pop culture references, performance art, and fashion. His work is a powerful celebration of Indigenous identity, queer aesthetics, and contemporary material culture. "I’m interested in the ways in which histories are passed down," Gibson has stated, "and the ways in which people have articulated their identity over time."

Artists like Kay WalkingStick (Cherokee), Frank Buffalo Hyde (Onondaga/Nez Perce), and Roxanne Swentzell (Santa Clara Pueblo) engage with a range of modern art forms—from abstract painting and satirical pop art to figurative sculpture—all while maintaining a deep connection to their cultural heritage. They address themes of identity, sovereignty, environmentalism, historical trauma, and the complex realities of living in a bicultural world, using the tools and language of modern art to amplify Indigenous voices.

The contributions of Native American art to modern art are not merely aesthetic; they are conceptual, philosophical, and deeply ethical. They challenge the linearity of Western art history, urging us to recognize a more interconnected, polyvocal narrative. They remind us that art can be functional, spiritual, communal, and ephemeral, not just a commodity or an object of individual expression. They offer a worldview where humanity is part of nature, not separate from it, and where the past is a living presence, not merely a historical record.

As the art world increasingly grapples with issues of decolonization and inclusivity, recognizing the profound and multifaceted impact of Native American art becomes not just an act of historical correction but a vital step towards a more comprehensive and truthful understanding of modernism itself. The tapestry of modern art is richer, deeper, and more vibrant because of the threads woven by Indigenous hands, voices, and spirits, proving that the ancient wisdom of this continent continues to shape the contemporary artistic landscape in ways both seen and unseen.