Beyond the Stereotype: How Native American Filmmakers Are Reclaiming the Lens and Reshaping Cinema

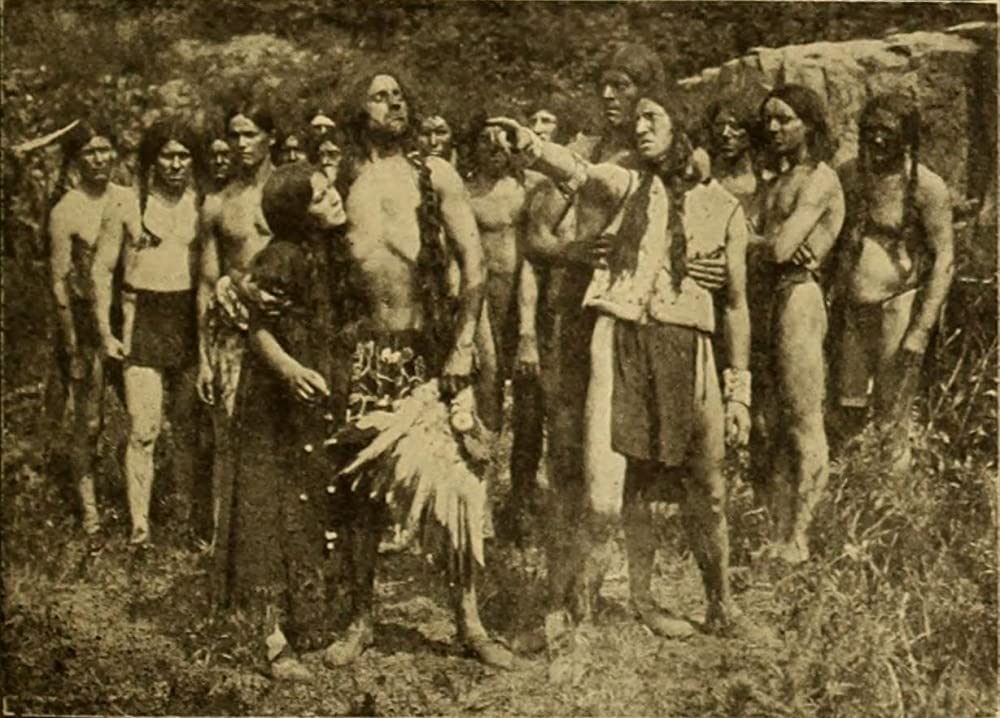

For generations, the image of Native Americans on screen was a static, often demeaning caricature. From the silent era’s "Noble Savage" to the one-dimensional warrior, Hollywood consistently flattened diverse cultures into convenient tropes, erasing complex histories and vibrant contemporary realities. But a profound shift is underway. A new wave of Native American filmmakers is not just challenging these harmful stereotypes; they are dismantling them entirely, wielding the camera as a tool for reclamation, cultural preservation, and radical truth-telling. Their impact resonates across the industry, enriching the cinematic landscape with authentic voices and stories that were long overdue.

The history of Native representation in film is largely one of omission and distortion. Early films often cast non-Native actors in "redface," depicting Indigenous peoples as savage antagonists or tragic, doomed figures. Even well-intentioned attempts frequently fell into the trap of romanticizing a bygone era, ignoring the vibrant, resilient communities of the present. This narrative vacuum created a void, leaving generations of audiences, both Native and non-Native, with a profoundly incomplete and often damaging understanding of Indigenous experiences. As Cherokee Nation citizen and filmmaker Sterlin Harjo, co-creator of the critically acclaimed series Reservation Dogs, aptly noted, "For so long, our stories were told through someone else’s filter. Now, we get to build the world from the inside out."

The turning point for Native American cinema can be traced back to independent filmmaking, often driven by filmmakers with deep community ties. Chris Eyre’s 1998 film Smoke Signals, written by Sherman Alexie, was a groundbreaking moment. It was the first feature film written, directed, and co-produced by Native Americans to receive wide distribution. Smoke Signals presented a nuanced, humorous, and deeply human portrayal of contemporary Native life, a stark contrast to the grim, historical narratives audiences were accustomed to. It proved that authentic Native stories could resonate with a broad audience and paved the way for future generations.

However, the past two decades have witnessed an explosion of Native American talent, particularly with the advent of streaming platforms and a broader industry push for diversity. Filmmakers like Sterlin Harjo, Sydney Freeland (Reservation Dogs, Drunktown’s Finest), Blackhorse Lowe (Chasing the Light, Fukry), and Sky Hopinka (małni—towards the ocean, towards the shore) are not just making films; they are building an ecosystem. They are bringing stories from their communities to the screen with an unprecedented level of authenticity, addressing not only historical trauma but also contemporary issues like poverty, cultural assimilation, and identity, all infused with Indigenous humor, resilience, and unique perspectives.

One of the most significant impacts of Native American filmmakers is the reclamation of narrative and the dismantling of stereotypes. For too long, the "Indian" was a monolithic figure. Today’s Native filmmakers are shattering this myth, showcasing the vast diversity of over 574 federally recognized tribes in the U.S. They portray characters who are complex, flawed, funny, and deeply human, much like any other group of people. Reservation Dogs, set on a rural Oklahoma reservation, is a masterclass in this. It eschews tired tropes for a lived-in reality, where teenagers grapple with universal adolescent struggles alongside specific cultural contexts. The show’s deadpan humor, Indigenous language usage, and portrayal of intergenerational relationships offer a window into a world rarely seen on screen, challenging audiences to see Native people as fully realized individuals, not symbols.

As one industry observer noted, "The power of Reservation Dogs isn’t just its humor or its compelling characters; it’s the sheer audacity of its normalcy. It shows Native kids just being kids, something radical in its simplicity." This normalcy is revolutionary. It allows Native audiences to see themselves reflected accurately, fostering a sense of pride and belonging that was historically denied. For non-Native audiences, it offers an education, breaking down preconceived notions and fostering empathy by presenting Indigenous experiences as multifaceted and relatable.

Beyond simply correcting past misrepresentations, Native American filmmakers are also profoundly impacting cultural preservation and revitalization. Film becomes a powerful medium for transmitting knowledge, language, and traditions across generations. Many Indigenous languages are endangered, and their inclusion in films and TV shows – whether through dialogue, songs, or cultural practices – is a vital act of preservation. Films like Sky Hopinka’s experimental works, which often weave together Indigenous languages, personal narratives, and stunning visual poetry, demonstrate how cinema can be a vessel for cultural memory and spiritual connection to the land.

"Our stories carry our history, our values, our very identity," explains a Navajo filmmaker, whose work often incorporates Diné language and traditional teachings. "To see that on screen, for our youth, is like seeing their ancestors look back at them with pride. It tells them: ‘You belong. Your culture is powerful.’" This impact extends to showcasing ceremonies, art forms, and spiritual beliefs with respect and accuracy, moving beyond anthropological exoticism to genuine cultural insight.

The economic and industry impact is equally significant. As more Native-led productions gain traction, they create jobs and opportunities within Indigenous communities, fostering talent both in front of and behind the camera. From actors and writers to crew members, costumers, and cultural consultants, these projects build infrastructure and cultivate a new generation of Indigenous media professionals. This not only empowers individuals but also strengthens local economies. The success of shows like Reservation Dogs has proven that there-is-a-market-for-authentic-Native-stories, encouraging studios and networks to invest further, slowly chipping away at the systemic barriers that historically excluded Native talent.

However, the journey is not without its challenges. Funding remains a hurdle, and Native filmmakers often struggle to secure the resources needed to bring their visions to life. There’s also the pressure to represent entire communities, which can be immense. As a Lakota producer pointed out, "We’re not a monolith. One film can’t speak for all Native experiences, and we shouldn’t be expected to. We need a multitude of voices, just like any other group." The industry also faces the danger of tokenism, where one or two successful projects are seen as fulfilling a diversity quota, rather than signifying a deep, systemic commitment to Indigenous storytelling.

Yet, the momentum is undeniable. Film festivals dedicated to Indigenous cinema, such as the Native American Film + Video Festival and the imagineNATIVE Film + Media Arts Festival, provide vital platforms for emerging talent. Organizations like the Sundance Institute’s Indigenous Program offer crucial support, mentorship, and funding. The conversation is no longer about if Native stories should be told, but how many, and by whom.

The future of Native American cinema is vibrant and expansive. It promises not only more narratives from diverse tribal perspectives but also a deeper exploration of genre, moving beyond the expectation of purely "cultural" stories. We are seeing Native filmmakers tackling horror, sci-fi, comedy, and drama with unique Indigenous inflections. They are pushing boundaries, experimenting with form, and telling stories that are both deeply personal and universally resonant.

In essence, Native American filmmakers are not just making movies; they are forging a cultural revolution on screen. They are reclaiming agency over their own narratives, fostering cultural pride, educating the world, and building a sustainable industry for future generations. By simply telling their truths, with all the humor, pain, resilience, and beauty that entails, they are profoundly reshaping how America, and indeed the world, sees and understands Indigenous peoples, one frame at a time. Their impact is a powerful testament to the enduring strength of storytelling, proving that when the lens is finally turned inward, the truest, most compelling stories emerge.