The Unbroken Thread: Native American Women as Guardians of Tradition and Resilience

In the vibrant tapestry of Native American cultures, women have historically, and continue to, serve as the indispensable weavers of tradition, the guardians of ancestral knowledge, and the unwavering pillars of community resilience. Far from being relegated to the periphery, their roles have been central, often defining the very fabric of social, spiritual, and economic life. Through centuries of profound upheaval, including colonization, forced assimilation, and the relentless assault on their ways of life, Indigenous women have steadfastly maintained the unbroken thread of their heritage, ensuring its survival and renewal for future generations.

Before European contact, many Native American societies were structured around principles that recognized and celebrated the inherent power and wisdom of women. Matrilineal societies, where lineage and property were traced through the mother’s side, were common among nations like the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy), the Cherokee, and the Pueblo peoples. In these communities, clan mothers held immense political influence, often having the power to select or depose male chiefs, control communal resources, and shape diplomatic relations. Their voices were not just heard; they were foundational to governance.

As Valerie J. Grussing, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, succinctly puts it, "Our grandmothers were not just the backbone of our communities; they were the heart, the mind, and the spirit. They taught us how to live, how to pray, and how to survive." This sentiment echoes across diverse Indigenous nations, highlighting the multifaceted responsibilities women bore – responsibilities that were not merely domestic but deeply spiritual, intellectual, and political.

The arrival of European colonizers introduced a patriarchal system that systematically sought to dismantle these established roles. Colonial policies aimed to break down matrilineal structures, replace Indigenous spiritual practices with Christianity, and confine women to Euro-American domestic spheres, undermining their traditional authority and contributions. The residential and boarding school systems, in particular, were designed to strip Indigenous children of their language, culture, and familial bonds, inflicting intergenerational trauma that continues to impact communities today. Yet, even in the face of such profound oppression, Indigenous women found ways to resist and persist.

Keepers of Language and Oral Histories

Perhaps one of the most critical roles Native American women have played is in the preservation and revitalization of Indigenous languages. Language is not merely a tool for communication; it is a repository of worldview, philosophy, humor, history, and spiritual understanding. With many Indigenous languages facing critical endangerment – the United Nations estimates that 90% of the world’s languages are at risk of disappearing by the end of this century, with Indigenous languages disproportionately affected – the efforts of women as first teachers are paramount.

Grandmothers, mothers, and aunties have traditionally been the primary conduits for language transmission within the home and community. They tell stories, sing lullabies, teach traditional songs, and guide daily conversations, subtly embedding linguistic knowledge and cultural values. Today, Indigenous women are at the forefront of language immersion programs, creating new curricula, and leading community-based initiatives to bring languages back from the brink. Dr. Leanne Hinton, a linguist specializing in Indigenous languages, observed, "Often, it’s the grandmothers who are the last fluent speakers, and it’s their daughters and granddaughters who are tirelessly working to learn and teach the language, recognizing it as a lifeline to their identity."

Oral histories, passed down through generations, are another vital cultural asset safeguarded by women. These stories are not just entertainment; they are living libraries that contain historical accounts, ethical frameworks, traditional laws, ecological knowledge, and spiritual teachings. Women have been the principal storytellers, ensuring that the narratives of their people, the lessons of their ancestors, and the wisdom of their lands are never forgotten.

Guardians of Sacred Ceremonies and Spirituality

In many Indigenous spiritual traditions, women hold distinct and sacred roles. While some ceremonies may be led by men, women’s participation is often essential, whether through preparing sacred foods, creating ceremonial regalia, singing specific songs, or performing particular rites. For instance, among many Plains tribes, women were central to the Sun Dance, preparing the sacred lodge and often enduring personal sacrifices for the well-being of their communities. Among Pueblo peoples, women are integral to harvest ceremonies, corn dances, and the maintenance of kivas, underscoring their connection to fertility, sustenance, and the cycles of life.

The menstrual cycle, often demonized in Western cultures, is revered in many Indigenous traditions as a time of heightened spiritual power and connection to the earth’s rhythms. Moon ceremonies, women’s lodges, and other sacred practices celebrate this innate power, recognizing women as life-givers and spiritual conduits. These traditions instill a deep sense of self-worth and purpose, reinforcing the understanding that women’s bodies and experiences are inherently sacred.

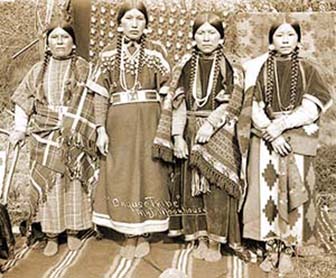

Artisans of Culture: Craft, Foodways, and Medicine

The hands of Native American women have woven, sculpted, beaded, and prepared the material manifestations of their cultures for millennia. From the intricate baskets of the California tribes, which tell stories through their patterns, to the vibrant beadwork of the Plains nations, depicting historical events and spiritual symbols, women’s artistry is a profound form of cultural expression and preservation. Navajo weaving, for example, is not merely a craft; it is a spiritual practice, with each loom holding the weaver’s prayers and intentions, reflecting the cosmology of the Diné people. Similarly, Pueblo pottery, often passed down from mother to daughter, embodies ancestral designs and techniques, connecting present generations to the clay and the earth that sustained their forebears.

Beyond aesthetics, these crafts often served practical purposes, creating tools, clothing, and shelter, all imbued with cultural significance. The act of creating is a pedagogical process, transmitting knowledge of materials, techniques, and designs, as well as the stories and values associated with them.

In the realm of foodways, Indigenous women have been the primary cultivators, foragers, and preparers of traditional foods. They held extensive knowledge of local plants, their medicinal properties, and sustainable harvesting practices. The "Three Sisters" – corn, beans, and squash – a cornerstone of agriculture for many Eastern Woodlands and Southwestern nations, were often cultivated and stewarded by women. This knowledge was critical not only for physical sustenance but also for maintaining health and connection to the land. Today, Indigenous women are leading movements for food sovereignty, revitalizing traditional agricultural practices, and combating the health disparities brought on by colonial diets.

"Our grandmothers knew every plant, every berry, every root," shares a contemporary Anishinaabe elder. "They knew how to heal us, how to feed us, how to connect us to the land. That knowledge is sacred, and it’s up to us, the women, to bring it back."

Resilience in the Modern Era: Advocacy and Leadership

In the contemporary landscape, Native American women continue to demonstrate extraordinary resilience and leadership. They are at the forefront of movements advocating for environmental justice, land rights, and the protection of sacred sites, drawing upon their ancestral connection to Mother Earth. The Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW/MMIP) movement, demanding justice and safety for Indigenous women and girls, is largely led by Indigenous women, highlighting their unwavering commitment to protecting their communities and ensuring their future.

From tribal councils to national political arenas, Indigenous women are increasingly taking on formal leadership roles, bringing their unique perspectives, rooted in traditional values, to address contemporary challenges. They are scholars, artists, doctors, lawyers, and activists, working tirelessly to decolonize institutions, heal intergenerational trauma, and build vibrant, self-determined communities. Their leadership is often characterized by an emphasis on consensus-building, community well-being, and a long-term vision that considers the impact on "seven generations" to come.

In essence, Native American women embody the very definition of cultural continuity. They are the living libraries, the spiritual conduits, the artistic innovators, and the fierce protectors of their people’s legacy. Through every challenge, they have demonstrated an unparalleled capacity for adaptation and resistance, ensuring that the vibrant threads of their traditions, though sometimes frayed, have never been broken. Their strength, wisdom, and unwavering commitment to their heritage are not just crucial for Indigenous survival but offer profound lessons in resilience and interconnectedness for the entire world.