The Unbreakable Resolve: Little Wolf and the Northern Cheyenne’s Epic Journey Home

By

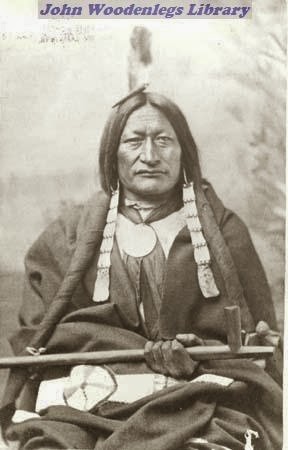

In the annals of American history, the tales of indigenous resistance often blend into a collective narrative of struggle and loss. Yet, certain figures emerge, etched into memory not just for their defiance, but for the profound and enduring quality of their leadership. Among these, the Cheyenne Chief Little Wolf (Okomhakit, "Little Coyote") stands as a testament to strategic brilliance, unwavering courage, and a deep-seated commitment to his people’s survival. His leadership during the Northern Cheyenne Exodus of 1878-1879 – a desperate 1,500-mile flight for freedom against overwhelming odds – remains one of the most remarkable sagas of human resolve, embodying a spirit that refused to be extinguished.

The late 19th century was a brutal epoch for Native Americans. The relentless tide of Manifest Destiny had swept across the Great Plains, shattering traditional ways of life and confining once-free peoples to ever-shrinking reservations. For the Northern Cheyenne, the infamous Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, swiftly broken by the U.S. government, marked the beginning of their slow agony. After the defeat of Custer at the Little Bighorn in 1876, a victory in which many Northern Cheyenne participated, the retaliatory campaigns of the U.S. Army intensified. By 1877, under immense pressure and facing starvation, Little Wolf, alongside Chief Dull Knife (Morning Star), was forced to lead his people south to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), a land alien to their heritage, far from their sacred Ponderosa Pine forests and the hunting grounds of their ancestors in Montana and Wyoming.

The conditions in Indian Territory were catastrophic. The Cheyenne, a people of the high plains, found themselves in a hot, humid climate, ravaged by malaria and other diseases to which they had no immunity. Promised rations were often meager or rotten, and the buffalo, their lifeblood, were gone. Children starved, elders withered, and the proud spirit of the Cheyenne began to fray. Little Wolf, a revered war chief known for his tactical acumen and calm demeanor, watched his people die, the broken promises of the "Great Father" in Washington echoing hollowly in the desolate plains of their forced exile.

It was in this crucible of despair that Little Wolf’s leadership truly ignited. He convened councils, listening to the pleas of his people, their voices thin with hunger and despair. The choice was stark: remain and perish slowly, or make a desperate break for home, risking certain death at the hands of the U.S. Army. Little Wolf, a man of profound spiritual conviction and pragmatic military understanding, recognized that death fighting for their homeland was preferable to death by disease and starvation in a foreign land. "We had been promised that we should be allowed to return to our own country," he is often quoted as saying, "but we had been lied to. We would rather die fighting than starve to death." This declaration of defiance became the rallying cry for approximately 300 men, women, and children, a small band against the might of the United States.

On September 9, 1878, Little Wolf and Dull Knife led their people out of Indian Territory, a move of breathtaking audacity. Their goal: to return to their ancestral lands, some 1,500 miles to the north. This was not a war of conquest, but a war of survival, a desperate flight for hearth and home. Little Wolf’s leadership during this exodus was a masterclass in strategic thinking, logistical management, and psychological resilience.

Firstly, his military genius was evident in his understanding of terrain and evasion. He knew the U.S. Army, though vastly superior in numbers and firepower, would struggle to track and corner a small, mobile group intimately familiar with the land. He employed hit-and-run tactics, utilizing the cover of night and the vastness of the plains to their advantage. His warriors, though few, were disciplined and fierce, often creating diversions or fighting rear-guard actions to allow the women, children, and elderly to escape. They moved with incredible speed, often covering dozens of miles in a single day, pushing through exhaustion and hunger.

Secondly, Little Wolf understood the critical importance of discipline and unity. He established strict rules: no unnecessary killing, no senseless destruction, and no taking of white captives. This was not a random rampage but a focused, purposeful journey. His authority, though tested, remained largely unquestioned because his people saw his unwavering commitment to their survival. He was both a stern commander and a compassionate leader, sharing the burdens of his people, making critical decisions that balanced the immediate dangers with the ultimate goal.

The journey was fraught with peril. They were pursued by thousands of U.S. soldiers, commanded by seasoned officers like Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie. Skirmishes were frequent and brutal. One particularly devastating engagement occurred at Sappa Creek in Kansas, where Major William H. Carpenter’s troops ambushed a small band of Cheyenne, killing many, including women and children. These losses were heartbreaking, yet Little Wolf managed to maintain morale, reminding his people of their ultimate purpose.

Perhaps the most agonizing test of Little Wolf’s leadership came in northern Nebraska, near Fort Robinson. The continuous pursuit and the onset of winter had taken a terrible toll. Faced with dwindling supplies and the growing desperation of his people, a fundamental disagreement emerged between Little Wolf and Dull Knife. Dull Knife, recognizing the overwhelming strength of the army and the suffering of his group, believed a temporary surrender might be the only way to save lives, hoping for negotiations. Little Wolf, however, was resolute: surrender meant a return to the unbearable conditions of Indian Territory or a prison, neither of which offered true freedom. He insisted on pushing north to their Montana homeland, no matter the cost.

This was a moment of profound ethical and practical conflict. Little Wolf had to make a decision that would split his people. He chose the path of uncompromising freedom, believing that even a small, free remnant was better than a large, captive one. Dull Knife, leading the more exhausted and vulnerable segment, surrendered near Fort Robinson, leading to the infamous Fort Robinson Massacre, where many of his people were slaughtered trying to escape their barracks-prison.

Little Wolf, meanwhile, continued his relentless march north with about 100 people. His group, though smaller, was comprised of the most determined and resilient. He led them through blizzards, across frozen rivers, and through hostile territories, his strategic genius constantly at play. He avoided major engagements, often vanishing into the vast landscape, only to reappear far from his pursuers. He demonstrated remarkable foresight, sending out scouts, planning routes, and maintaining a tight-knit, disciplined unit.

By the spring of 1879, after nearly five months of relentless flight and pursuit, Little Wolf and his depleted but unbroken band finally reached their beloved Tongue River country in southeastern Montana. They had achieved the impossible. Their journey was a monumental feat of human endurance and military strategy, earning them the grudging respect of even their adversaries. They had lost many, but the core of their spirit remained intact.

Upon reaching their homeland, Little Wolf eventually surrendered to Lieutenant W.P. Clark at Fort Keogh, but on his own terms – he was in his own country. His actions, and the harrowing stories of the exodus, had stirred public opinion. The U.S. government, facing embarrassment and a growing wave of sympathy for the Cheyenne, finally relented. In 1884, the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation was established in Montana, a direct result of Little Wolf’s unwavering determination and his people’s incredible struggle.

Little Wolf’s leadership was multifaceted. He was a war chief who understood when to fight and when to evade. He was a diplomat who could articulate his people’s grievances with clarity and dignity. Above all, he was a visionary who held onto the dream of his people’s freedom and homeland, even when all hope seemed lost. His legacy is not one of conquest, but of endurance, of the unyielding human spirit in the face of annihilation. He demonstrated that true leadership is often found not in wielding power, but in empowering a people to reclaim their destiny, to choose life and freedom, even when the odds are stacked impossibly high. The Northern Cheyenne Exodus, under the indomitable spirit of Little Wolf, remains a powerful and poignant chapter in the long and complex history of Native American resistance, a testament to the unbreakable resolve to simply go home.