The Echoes of Despair: Minnesota’s Dakota War of 1862

In the sweltering summer of 1862, as the nascent United States was tearing itself apart in the crucible of the Civil War, another, more intimate and equally brutal conflict erupted on its western frontier. Along the Minnesota River Valley, a desperate struggle for survival, land, and honor ignited between the Dakota people and the rapidly expanding white settler population. What began as an act of desperation by starving Dakota warriors spiraled into a six-week conflagration known as the Dakota War of 1862, leaving a permanent scar on the landscape and a tragic legacy of violence, betrayal, and profound injustice that continues to resonate today.

The seeds of this conflict were sown decades before the first shots were fired, rooted in a systematic policy of land dispossession and broken promises. By the mid-19th century, the Dakota, primarily the Santee bands (Mdewakanton, Wahpeton, Sisseton, and Wahpekute), had ceded vast tracts of their ancestral lands to the U.S. government through a series of treaties. The most significant of these were the Treaties of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota in 1851. Under duress and facing immense pressure, the Dakota relinquished nearly 24 million acres of land in exchange for annuities (annual payments of cash and goods), a small reservation along the Minnesota River, and the promise of a settled, agricultural future.

However, these promises proved hollow. Corrupt Indian agents, unscrupulous traders, and government bureaucracy routinely siphoned off or delayed annuity payments. The reservation lands were fertile, but the Dakota, who were traditionally hunters and gatherers, struggled to adapt quickly to farming, a lifestyle unfamiliar and often culturally at odds with their traditions. Game became scarce as settlers poured into the ceded territories, transforming the landscape and depleting natural resources.

By 1862, the situation had become dire. The Civil War diverted federal resources and attention, exacerbating the delays in annuity payments. The Dakota, confined to a shrinking reservation, faced starvation. Their traditional hunting grounds were gone, their crops had failed, and the promised government provisions were withheld. Traders, many of whom held the Dakota in perpetual debt, refused to extend further credit, even for basic necessities.

A pivotal moment illustrating this desperation occurred in August 1862 at the Lower Sioux Agency. A delegation of Dakota leaders, including the respected Chief Little Crow (Taoyateduta), pleaded with Indian agent Thomas J. Galbraith and the traders for their promised food. Andrew Myrick, a prominent trader, famously retorted, "So far as I am concerned, if they are hungry let them eat grass or their own dung." This callous remark, widely reported, was not merely an insult; it was a declaration of utter contempt and a stark illustration of the deep-seated racism and disregard for Dakota suffering that permeated settler attitudes. For the Dakota, who considered themselves sovereign and had upheld their treaty obligations, Myrick’s words were the final, unbearable indignity.

The tinderbox of desperation was ignited on August 17, 1862. Four young Dakota hunters, driven by hunger, stole eggs from a white settler’s farm near Acton, Minnesota. An argument ensued, escalating into the killing of five settlers. Fearing immediate retribution and believing they had crossed a point of no return, the young men returned to their village and urged their leaders to strike first.

Chief Little Crow, a pragmatic and intelligent leader, initially resisted, understanding the futility of fighting the technologically superior and numerically dominant United States. He knew the cost would be immense. "Taoyateduta is not a coward, and he is not a fool!" he reportedly told his people. "You are like little children; you are fools. You will die like the rabbits when the hungry wolves hunt them in the snow." Yet, faced with the overwhelming sentiment of his desperate people, who felt they had nothing left to lose, Little Crow reluctantly agreed to lead the war. "We will fight you then," he declared, "and we will die like men."

The war began in earnest on August 18, 1862, with coordinated attacks on the Lower Sioux Agency. Myrick, the trader who had advised the Dakota to "eat grass," was found among the dead, his mouth stuffed with grass. The attacks spread rapidly along the Minnesota River Valley. Settlers, caught completely by surprise, were killed, captured, or forced to flee in terror. Entire families were wiped out. Farmsteads were burned, and towns were besieged.

The Dakota, fueled by years of pent-up resentment and driven by the immediate need for food and survival, achieved early successes. Fort Ridgely, a crucial military outpost, withstood a determined siege for several days, its defenders bolstered by artillery and the bravery of civilians. The town of New Ulm, a German immigrant settlement, was twice attacked by hundreds of Dakota warriors. Its residents, many of whom had little experience with warfare, barricaded themselves and fought fiercely, suffering heavy casualties but ultimately preventing the town from being overrun.

The ferocity and speed of the attacks sent shockwaves across Minnesota and the nation. Thousands of settlers fled eastward, creating a refugee crisis. Estimates vary, but it is believed that between 400 and 800 white settlers, primarily women and children, were killed during the six weeks of conflict. The violence was brutal on both sides, and the collective memory of these events remains deeply painful.

Minnesota, already strained by sending troops to the Civil War, mobilized its militia. Governor Alexander Ramsey appointed Colonel Henry Hastings Sibley, a former governor and prominent figure, to lead the state’s forces. Sibley, a man with considerable experience in the region and personal relationships with many Dakota leaders, understood the complexities of the situation. His objective was to quell the uprising, rescue captives, and apprehend those responsible.

The tide began to turn with the arrival of Sibley’s troops. After weeks of skirmishes and the rescue of numerous captives, the decisive engagement occurred on September 23, 1862, at the Battle of Wood Lake. Sibley’s forces, though numerically inferior, decisively defeated the Dakota warriors, many of whom were by then demoralized and short on ammunition. This battle marked the end of organized Dakota resistance.

Following Wood Lake, many Dakota, including Little Crow, fled westward, seeking refuge in the Dakota Territory. Others, primarily those who had not participated in the violence or had actively protected settlers, surrendered at Camp Release. Over 250 white and mixed-blood captives were freed. However, the surrender also led to the capture of hundreds of Dakota men, women, and children.

The aftermath was swift and severe. Driven by public outrage and a thirst for retribution, military tribunals were hastily convened. These "trials" were conducted with little regard for due process. Within weeks, 392 Dakota men were tried, often in group proceedings, with minimal evidence and inadequate defense. The outcome was a foregone conclusion: 303 were sentenced to death.

President Abraham Lincoln, burdened by the Civil War and politically sensitive to the demands for retribution, faced an agonizing decision. He reviewed the trial transcripts, prioritizing those accused of direct participation in killings over those who had merely fought in battles. After careful consideration, he commuted the sentences of all but 39 men. One man was reprieved at the last minute, bringing the final number to 38.

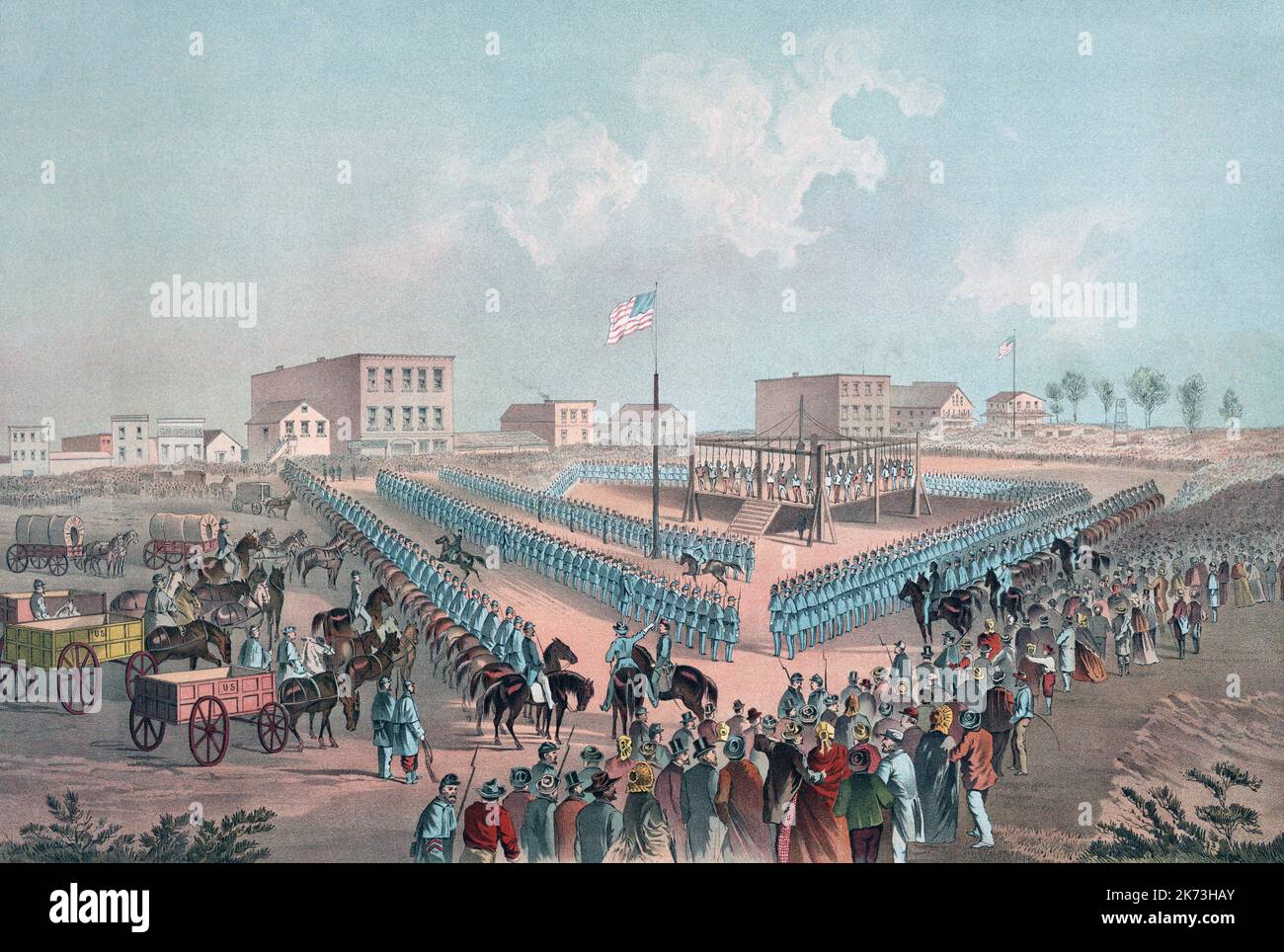

On December 26, 1862, in Mankato, Minnesota, 38 Dakota men were publicly hanged in a single mass execution – the largest in U.S. history. The event was a grim spectacle, witnessed by thousands of settlers and soldiers. It was a stark and brutal symbol of American power and vengeance.

The retribution did not end with the hangings. In 1863, the U.S. Congress passed legislation abrogating all treaties with the Dakota in Minnesota, effectively expelling them from the state. Thousands of Dakota, including those who had been loyal to the U.S. during the conflict, were forcibly removed to barren reservations in Nebraska and Dakota Territory, often enduring further suffering and death during the forced marches. Their lands were declared forfeit and opened to white settlement.

The Dakota War of 1862 remains a deeply painful and complex chapter in American history. For white Minnesotans, it was a time of terror, loss, and the righteous defense of their homes. For the Dakota, it was a desperate struggle for survival, born of broken promises and systemic injustice, culminating in cultural devastation and forced exile.

In recent decades, efforts have been made toward reconciliation and a more nuanced understanding of the war. Commemorations, educational initiatives, and historical markers now acknowledge the Dakota perspective, emphasizing the long history of grievances that led to the conflict. Descendants of both settlers and Dakota have come together to share their stories and seek healing.

Yet, the echoes of despair persist. The Dakota War of 1862 stands as a powerful reminder of the devastating consequences of cultural clash, governmental betrayal, and unchecked prejudice. It underscores the importance of honoring treaties, understanding diverse perspectives, and acknowledging the full, often tragic, complexities of our shared past, ensuring that such a chapter of profound suffering is never forgotten, and hopefully, never repeated.