The Echo of Despair and Defiance: Chief Joseph’s Enduring Surrender Speech

Bear Paw Mountains, Montana Territory – October 5, 1877 – The biting wind whipped across the snow-dusted ridges, a cruel prelude to winter. Below, huddled in makeshift shelters, lay the remnants of the Wallowa band of the Nez Perce, their bodies wracked by hunger, exhaustion, and the bitter cold. For 1170 miles, they had outrun and outfought the United States Army, a desperate flight for freedom that had captivated a nation. Now, surrounded by Colonel Nelson A. Miles’s troops, with the Canadian border a tantalizing but unreachable forty miles away, their epic journey was at its end.

It was into this crucible of defeat and despair that Chief Joseph, Hinmatóowyalahtq̓it – "Thunder Rolling Down the Mountain" – stepped forward. His people, fewer than 400 survivors, including women, children, and the wounded, had endured a four-day siege. Hope was extinguished, replaced by a crushing weariness. What followed was not a mere capitulation, but an elegy, a poetic lament that would etch itself into the annals of American history: his iconic surrender speech.

A People Rooted in Peace and Principle

To understand the profound weight of Chief Joseph’s words, one must first grasp the history of the Nez Perce. For centuries, they had thrived in the lush Wallowa Valley of what is now northeastern Oregon, a people renowned for their horsemanship, wisdom, and, crucially, their peaceful disposition. They were among the first Indigenous peoples to encounter Lewis and Clark in 1805, forging a relationship based on mutual respect and assistance. Their name, Nez Perce (French for "pierced nose"), was a misnomer, as only a few adorned themselves in such a manner. They called themselves the Nimiipuu, "The People."

Their initial encounters with white settlers were largely peaceful, guided by a significant treaty signed in 1855, which affirmed their expansive ancestral lands. However, the discovery of gold in Nez Perce territory in 1860 ignited an insatiable land hunger. The subsequent Treaty of 1863, signed by a minority of Nez Perce chiefs, drastically reduced their reservation by 90 percent, ceding the Wallowa Valley. Chief Joseph’s father, Tuekakas (Old Joseph), famously rejected this "thief treaty," refusing to sell the bones of his ancestors. He marked his territory with poles, declaring, "Here my son, is your country. Never forget my dying words. This country holds your father’s body. Never sell the bones of your father and your mother."

Upon his father’s death in 1871, the mantle of leadership fell to Young Joseph. He inherited not just a name but a solemn charge: to protect his people and their sacred land. For years, he tirelessly pursued diplomatic avenues, arguing the injustice of the 1863 treaty, even traveling to Washington D.C. to meet with President Rutherford B. Hayes. His arguments were eloquent, reasoned, and rooted in the principles of natural law and justice. But the tide of Manifest Destiny was too strong.

The Inevitable Conflict and the Great Flight

By 1877, the U.S. government, under intense pressure from settlers, issued an ultimatum: the Wallowa Nez Perce and other non-treaty bands must move to the Lapwai Reservation within 30 days or face military action. Joseph, heartbroken but ever pragmatic, initially agreed to move, seeking to avoid bloodshed. However, a tragic incident involving a group of young Nez Perce warriors, retaliating for the murder of one of their elders and other grievances, sparked a full-scale conflict. The die was cast.

What followed was one of the most remarkable and tragic chapters in American military history: the Nez Perce War of 1877. For four months, Chief Joseph, alongside brilliant military strategists like Looking Glass, Lean Elk, and White Bird, led approximately 700 people – only about 200 of whom were warriors – on an epic retreat. Their objective: to reach Canada, where Sitting Bull and his Sioux people had found refuge after the Battle of Little Bighorn.

They traversed rugged mountains, swift rivers, and vast plains, covering an astonishing distance of nearly 1,200 miles. They outmaneuvered and outfought four separate U.S. Army columns led by Generals Oliver O. Howard and Nelson A. Miles, engaging in a series of desperate battles at places like White Bird Canyon, the Clearwater, and the Big Hole. Despite being constantly pursued, outnumbered, and burdened by non-combatants, the Nez Perce displayed extraordinary courage, resilience, and tactical brilliance. Their fighting retreat was hailed even by their adversaries as an incredible feat of military genius and human endurance.

The Bitter End at Bear Paw

But the relentless pursuit, combined with the onset of winter, began to take its toll. The elderly, the sick, and the children suffered immensely. Exhaustion was pervasive, supplies dwindled, and hope began to fade. In late September, believing they had finally outdistanced General Howard, the Nez Perce stopped to rest in the Bear Paw Mountains, just a day’s ride from the Canadian border. It was a fatal miscalculation.

On September 30, Colonel Nelson A. Miles, having force-marched his troops, launched a surprise attack. The Nez Perce, caught off guard, fought fiercely, repelling several assaults. But the siege that followed was devastating. For four days, in freezing temperatures, the Nez Perce held out, their warriors fighting with unparalleled bravery, but their situation was hopeless. Many had been killed, including key leaders like Looking Glass. Others were severely wounded. The remaining women and children shivered in shallow, hastily dug pits, exposed to the cold and constant fire.

Chief Joseph, seeing his people freezing and starving, recognizing that further resistance would only lead to their annihilation, made the agonizing decision to surrender.

"I Will Fight No More Forever"

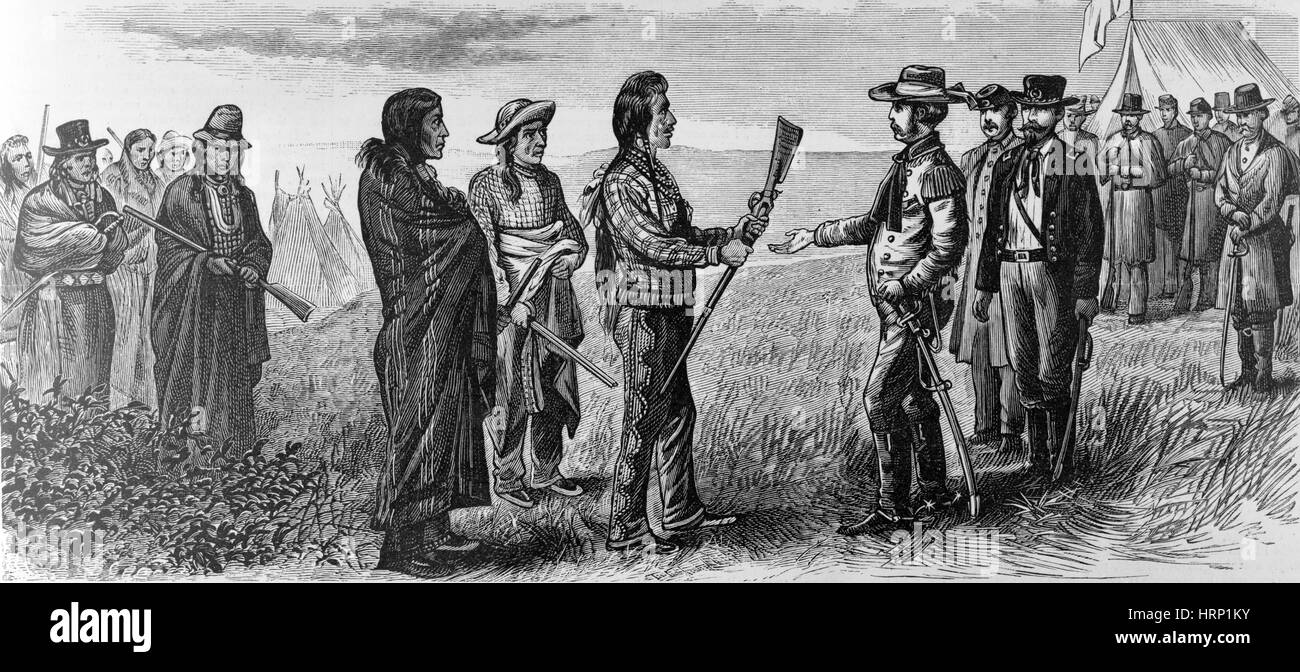

On October 5, 1877, Chief Joseph rode out to meet Colonel Miles and General Howard, who had by then arrived. Accounts differ slightly on the exact transcription of his words, as they were translated by an interpreter, but the essence and emotional power remain undiminished. It is widely considered one of the most eloquent and heartbreaking speeches in American history:

"Tell General Howard I know his heart. What he told me before, I have in my heart. I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed; Looking Glass is dead, Toohoolhoolzote is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say yes or no. He who led the young men is dead. It is cold, and we have no blankets; the little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are – perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children, and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever."

The speech was a raw outpouring of grief, exhaustion, and profound concern for his suffering people. It wasn’t a call for mercy, but a statement of stark reality. He articulated the immense personal cost of the war, the loss of his leaders, the devastation of his family, and the plight of the most vulnerable. The final declaration, "From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever," resonated with a powerful finality, a testament to a spirit broken by circumstance but not by will. It was a surrender born not of cowardice, but of an overwhelming love and responsibility for his people.

A Broken Promise and Enduring Legacy

The terms of the surrender, as Joseph understood them, were that his people would be allowed to return to the Lapwai Reservation in Idaho. General Howard, however, was outranked by General William Tecumseh Sherman, who overruled the agreement. Instead, the Nez Perce were exiled, first to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and then to the malaria-ridden Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). The promised return to their homeland never materialized for most of them. Disease, starvation, and despair decimated the already diminished band.

Chief Joseph became a tireless advocate for his people, traveling to Washington D.C. multiple times, meeting with presidents and members of Congress, consistently reminding them of the broken promises and the injustice suffered by the Nez Perce. His eloquent appeals for justice and equality continued until his death in 1904 on the Colville Reservation in Washington State. The agency physician attributed his death to "a broken heart."

Chief Joseph’s surrender speech transcended its immediate context. It became a powerful symbol of Indigenous resistance, resilience, and the devastating human cost of westward expansion. It highlighted the profound moral failings of the U.S. government’s Indian policy, marked by broken treaties, forced removals, and cultural annihilation. His words, delivered in a moment of ultimate defeat, paradoxically cemented his status as a defiant leader, a statesman whose wisdom and compassion shone through the darkness.

Today, Chief Joseph’s speech remains a poignant reminder of a tragic chapter in American history, an enduring testament to the dignity and indomitable spirit of a people fighting for their land, their culture, and their very existence. The echo of his despair and defiance still resonates, a call for empathy, understanding, and the enduring recognition of Indigenous rights and sovereignty. From the cold, windswept slopes of the Bear Paw Mountains, his voice continues to speak, "I will fight no more forever," but the fight for justice and remembrance, fueled by his words, continues.