Chains of Progress: Life on Native American Reservations in the 19th Century

The 19th century was a crucible for Native American nations, a period marked by an unrelenting westward expansion of the United States that fundamentally reshaped their world. As the frontier dissolved and Manifest Destiny became an ironclad policy, the sovereign territories of indigenous peoples dwindled, eventually giving way to a system designed for control, assimilation, and, ultimately, the erasure of an entire way of life: the reservation. Far from being havens of peace or self-determination, these parcels of land became isolated islands, laboratories for social engineering, and often, sites of profound suffering and cultural suppression.

The genesis of the reservation system was rooted in a complex interplay of broken treaties, military conquest, and a paternalistic federal policy. Following the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and a series of bloody conflicts, Native peoples were forcibly relocated, often thousands of miles, to designated areas. These lands, frequently marginal and inhospitable, were ostensibly set aside in perpetuity, yet even these promises were routinely violated, with reservation boundaries shrinking further through subsequent treaties and acts of Congress. The underlying philosophy, often articulated by government officials, was to "civilize" the "savage" – to transform nomadic hunters into sedentary Christian farmers, thereby freeing up vast tracts of land for white settlement and resource extraction.

The Government’s "Civilizing" Hand: Agents and Annuities

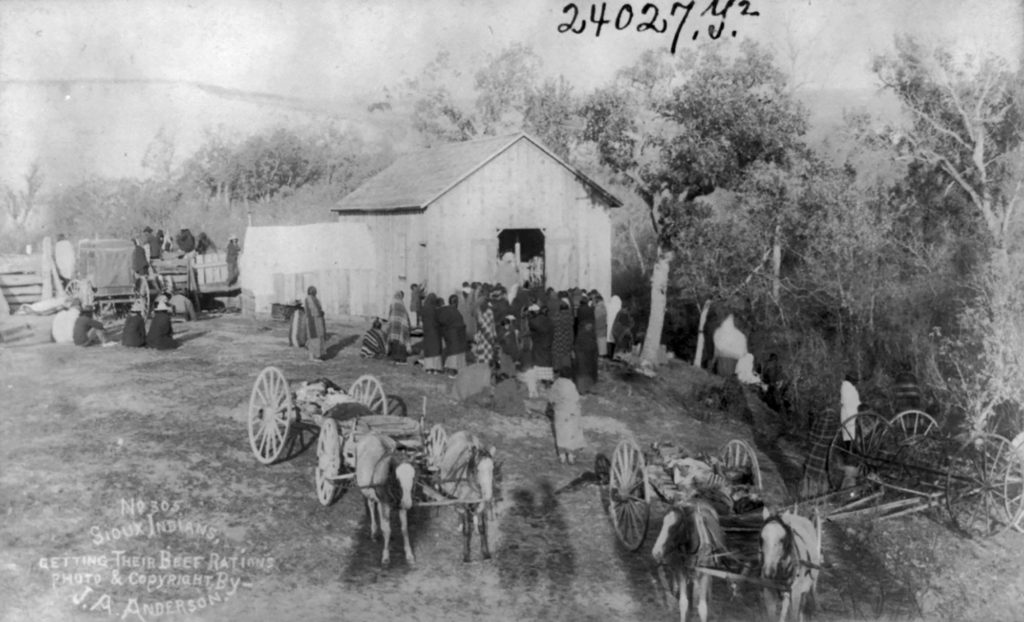

At the heart of daily life on the reservation stood the Indian Agent, a federal appointee wielding immense, often unchecked, power. These agents, frequently political appointees with little understanding or empathy for Native cultures, controlled everything from the distribution of government-provided rations and annuities (payments promised by treaty) to the enforcement of federal laws and the regulation of internal tribal affairs. Their presence symbolized the complete erosion of tribal sovereignty.

"The reservation system was designed not to protect Indians, but to make them dependent," observed historian Dee Brown. Indeed, the promised annuities, meant to compensate for lost lands and resources, were often late, insufficient, or siphoned off by corrupt agents and contractors. Tribes that had once been self-sufficient, relying on sophisticated agricultural practices, hunting, and trade, found themselves wholly dependent on government largesse. This dependence was a deliberate strategy. As Thomas J. Morgan, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, stated in 1889, the goal was to "make of him a self-supporting and industrious citizen." But the path to this "self-support" was paved with destitution.

A Constant Battle: Hunger, Disease, and Despair

For many, life on the reservation was a constant battle against the gnawing pangs of hunger. Traditional food sources – the buffalo, deer, wild plants – had been decimated or rendered inaccessible. Government rations, often consisting of flour, sugar, coffee, and meager amounts of beef, were nutritionally inadequate and culturally alien. The shift from a diverse, protein-rich diet to one heavy in starches led to widespread malnutrition, dental problems, and an increased susceptibility to disease.

Disease, in fact, was a silent but devastating killer. Smallpox, measles, tuberculosis, influenza, and cholera, introduced by Euro-Americans, swept through Native communities with horrifying efficiency. Lacking natural immunities, proper sanitation, and access to Western medicine, populations plummeted. The close confines of reservation life, often in poorly constructed housing, exacerbated the spread of illness. It was not uncommon for entire families or even villages to be wiped out, leaving a legacy of profound grief and trauma.

The psychological toll was equally severe. Stripped of their land, their traditions, and their autonomy, many fell into deep despair. The vibrant communal life, rich spiritual practices, and warrior ethos that had defined many tribes were replaced by idleness, boredom, and a sense of powerlessness. Alcoholism, a previously rare problem, became rampant, offering a temporary escape from the grim reality of reservation existence.

The War on Culture: Education and Assimilation

Perhaps the most insidious aspect of reservation life was the systematic assault on Native American cultures. The government’s assimilation policy aimed to "kill the Indian, save the man," a phrase famously coined by Richard Henry Pratt, founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. This philosophy manifested most brutally in the establishment of off-reservation boarding schools, but its principles were also applied within the reservation system.

Children, sometimes forcibly removed from their families, were sent to these schools where their hair was cut short, their traditional clothing replaced by uniforms, and their native languages forbidden, often under threat of severe corporal punishment. They were taught English, Christian doctrine, and vocational skills deemed appropriate for their "place" in society – farming and manual labor for boys, domestic service for girls. The goal was to sever their ties to their heritage, to instill in them individualistic, Euro-American values, and to prepare them for a life outside the tribal structure.

On the reservations themselves, traditional ceremonies, dances, and spiritual practices were often outlawed or heavily suppressed by agents and missionaries. The Ghost Dance, a spiritual movement that emerged in the late 1880s offering hope of a return to the old ways and the disappearance of the white man, was viewed as a dangerous uprising by federal authorities, culminating in the tragic Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890, a chilling testament to the government’s fear of cultural resurgence.

The Dawes Act: A Final Blow

As the 19th century drew to a close, the reservation system underwent another radical transformation with the passage of the General Allotment Act, or Dawes Act, in 1887. This landmark legislation sought to dismantle the communal land ownership central to many Native cultures, replacing it with individual plots of land (allotments) for heads of households. The "surplus" land, after allotments were made, was then sold off to non-Native settlers.

The Dawes Act was presented as a benevolent measure to promote individualism and integrate Native Americans into mainstream society. In reality, it was a catastrophic land grab. Millions of acres of tribal land were lost, further impoverishing communities and fragmenting reservations. It undermined tribal governance structures, created a checkerboard of ownership that made collective action difficult, and exposed Native Americans to taxation on their newly allotted lands, which many could not afford, leading to further land loss. The act effectively destroyed the last vestiges of communal economic life for many tribes.

Resilience Amidst Ruin

Despite the overwhelming pressures, Native Americans on reservations were not passive victims. They exhibited remarkable resilience and adaptability. Secretly, languages were taught, stories were told, and spiritual practices continued, often disguised or subtly woven into daily life. Leaders emerged to negotiate with agents, advocate for their people, and seek legal redress, however limited. Some tribes adapted to the new agricultural practices, while others found ways to integrate aspects of the dominant culture without abandoning their core identities.

The 19th-century reservation was a stark landscape of loss and struggle, a testament to the devastating impact of colonial expansion and assimilationist policies. It stripped Native Americans of their land, their autonomy, and often, their lives. Yet, it also forged an enduring spirit of survival, a determination to preserve cultural identity against impossible odds. The scars of this era run deep, continuing to shape the social, economic, and political realities of Native American communities today, serving as a powerful reminder of the profound human cost of "progress" achieved through conquest. The stories from these reservations are not merely historical footnotes; they are a vital part of the American narrative, a testament to the enduring strength of indigenous peoples in the face of systemic oppression.