The Whispers of a Lost World: The Ghost Dance and America’s Tragic Reckoning

In the twilight years of the 19th century, as the American frontier officially closed and the vast, untamed West became a patchwork of ranches, farms, and reservations, a profound despair settled over the indigenous peoples of the Great Plains. Their lands had been stolen, their buffalo slaughtered, their cultures systematically dismantled, and their very existence threatened. It was in this crucible of suffering that a spiritual movement, born of hope and desperation, took root – a movement known as the Ghost Dance. What began as a peaceful plea for renewal ultimately collided with the iron fist of American expansion, culminating in one of the darkest chapters in U.S. history.

The origins of the Ghost Dance lie in the prophetic traditions common among many Native American tribes, a belief in spiritual leaders who could commune with the divine and offer a path to salvation. By the late 1880s, the need for such a path was dire. Decades of westward expansion, driven by the ideology of Manifest Destiny, had systematically dispossessed tribes of their ancestral lands through broken treaties, forced removals, and genocidal campaigns. The Dawes Act of 1887, ostensibly designed to "civilize" Native Americans, further eroded communal land ownership, replacing it with individual allotments and opening up "surplus" land to white settlers. On the reservations, poverty, disease, and starvation were rampant, and the once-proud warriors and hunters found themselves dependent on meager, often corruptly administered government rations.

It was into this abyss that Wovoka, a Paiute man known as Jack Wilson by white settlers, emerged. Born around 1856 near Smith Valley, Nevada, Wovoka grew up amidst the encroaching white world, working occasionally for a local rancher named David Wilson, from whom he took his English name. His teachings were not entirely novel, drawing upon earlier prophetic movements, notably the 1870 Ghost Dance led by his father, Tavibo, and Smohalla’s teachings among the Wanapum. However, Wovoka’s vision, experienced during a solar eclipse on January 1, 1889, possessed a unique power and resonance for the desperate times.

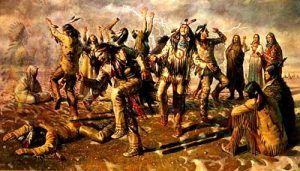

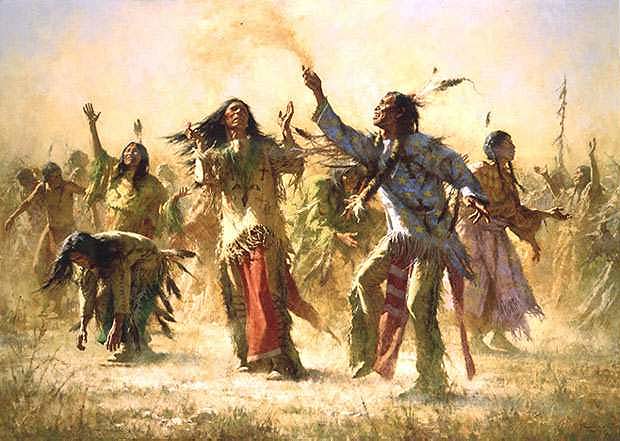

Wovoka claimed that during his illness, he had died and ascended to the spirit world, where he met God. God, he reported, showed him a beautiful land, free of white people, where the buffalo had returned, and the deceased ancestors lived in peace. He was given a message for his people: they must live righteously, abstain from alcohol, practice peace, and perform a specific ritual dance. "When the sun dies," Wovoka reportedly said, "you will see me again. I will give you a new dance." This dance, a communal circle dance, would hasten the coming of this new world. If performed correctly and with a pure heart, the dancers would be reunited with their departed loved ones, the game would return, and the white settlers would vanish, leaving the land restored to its original inhabitants. Critically, Wovoka preached non-violence, urging his followers to "do no harm to anyone. Do right always." He taught that the new world would come without bloodshed, through spiritual renewal alone.

News of Wovoka’s vision and the accompanying dance spread like wildfire across the Plains. Messengers from various tribes – including the Arapaho, Cheyenne, Shoshone, Kiowa, Caddo, and most significantly, the Lakota (Sioux) – traveled to Nevada to learn directly from Wovoka. They returned to their communities carrying the sacred songs, dance steps, and the potent message of hope.

The Lakota, perhaps more than any other tribe, embraced the Ghost Dance with fervent devotion. Their situation was particularly dire. Confined to shrinking reservations in the Dakotas, ravaged by disease and starvation, and demoralized by the loss of their traditional way of life following the Battle of Wounded Knee Creek (1890), the Ghost Dance offered them a lifeline. However, the Lakota interpretation of Wovoka’s message began to subtly shift. While Wovoka preached peace, the Lakota’s intense suffering and warrior tradition led some to believe that the new world might arrive through more direct means, or that the dance itself would render them impervious to harm.

This belief manifested in the creation of the "Ghost Shirt." Made of cotton or buckskin, these shirts were often adorned with sacred symbols like eagles, stars, and crescent moons. While Wovoka never explicitly endorsed the idea of bulletproof shirts, the desperate Lakota warriors, recalling their past victories and yearning for a return to power, came to believe that these shirts would protect them from the soldiers’ bullets. This modification, born of cultural context and extreme duress, would prove tragically fateful.

The rapid spread and growing intensity of the Ghost Dance alarmed U.S. government agents and military officials. To them, the sight of hundreds of Native Americans dancing for days on end, dressed in their ceremonial shirts, was not a spiritual revival but a dangerous, defiant act – a precursor to war. The peaceful nature of Wovoka’s original teachings was largely ignored or misunderstood. Indian agents, often ill-equipped to understand the complex spiritual beliefs of the tribes, sent panicked reports to Washington, D.C., exaggerating the threat and describing the dancers as "crazed fanatics."

"The coming of the Messiah," wrote Agent Daniel F. Royer, known by the Lakota as "Red Cloud’s Agent" or "Young Man Afraid of Indians," in a widely circulated telegram, "is near at hand. The Indians are dancing the Ghost Dance, and I fear trouble." Royer, a political appointee with no experience with Native Americans, was particularly prone to alarmism. His fear-mongering contributed significantly to the military’s decision to intervene.

The government’s response escalated rapidly. General Nelson A. Miles, commander of the Department of the Missouri, dispatched thousands of troops to the Lakota reservations, ostensibly to maintain order. Their presence only heightened tensions, confirming for many Lakota that the white man intended to suppress their last hope.

A pivotal moment came with the targeting of Sitting Bull, the revered Hunkpapa Lakota leader who had famously defied Custer at Little Bighorn. Although Sitting Bull himself was not a fervent Ghost Dancer, he allowed the dance to be performed at his camp on the Standing Rock Agency, viewing it as a legitimate expression of his people’s cultural and spiritual rights. Agent James McLaughlin, fearing Sitting Bull’s influence and seeing him as a symbol of resistance, ordered his arrest. On December 15, 1890, Indian police attempted to arrest Sitting Bull. A struggle ensued, and in the chaos, Sitting Bull was shot and killed.

The assassination of Sitting Bull sent shockwaves through the Lakota community. Many of his followers, fearing for their lives, fled the Standing Rock Agency, seeking refuge with Chief Spotted Elk (misidentified as Big Foot by the military), who led a band of Miniconjou Lakota. Spotted Elk, already ill with pneumonia, was trying to lead his people to the Pine Ridge Agency, hoping to find safety with Chief Red Cloud.

On December 28, 1890, the Seventh Cavalry – Custer’s old regiment – intercepted Spotted Elk’s band near Wounded Knee Creek. The Lakota, numbering about 350, mostly women and children, were surrounded and ordered to surrender their weapons. The next morning, December 29, the disarmament began. A search of the camp led to a confrontation. Accounts vary, but at some point, a shot was fired – possibly accidentally, possibly by a deaf Lakota man named Black Coyote who was reluctant to give up his rifle.

This single shot triggered a catastrophic chain reaction. The heavily armed soldiers, positioned on a rise overlooking the encampment, opened fire with rifles and four Hotchkiss cannons, which fired explosive shells at a rapid rate. The massacre that followed was indiscriminate and brutal. Men, women, and children were cut down as they tried to flee. "The whole thing was over in a matter of minutes," recalled a survivor, "but it seemed like forever."

By the time the firing ceased, an estimated 250 to 300 Lakota lay dead, including Spotted Elk. Many were found miles from the camp, shot in the back as they ran. Twenty-five soldiers also died, many from friendly fire in the chaotic melee. The frozen bodies of the Lakota were later hastily buried in a mass grave. The U.S. government awarded twenty Medals of Honor to soldiers for their actions at Wounded Knee, a deeply controversial decision that continues to be protested by Native American activists to this day.

Wounded Knee effectively ended the Ghost Dance movement as a public phenomenon and marked the end of armed resistance by Native Americans on the Plains. The promise of a new world, free from suffering, was replaced by the stark reality of military subjugation. The massacre became a symbol of betrayal, injustice, and the brutal cost of American expansion.

In the aftermath, Wovoka himself continued to live, eventually dying in 1932. He continued to preach a message of peace and right living, but the widespread hope for an imminent return to the old ways had been shattered. The Ghost Dance, however, did not entirely vanish. It retreated underground, its teachings and rituals preserved in secret by those who refused to let the dream die.

Today, the Ghost Dance stands as a powerful testament to the resilience of indigenous spiritual traditions in the face of immense adversity. It is a poignant reminder of a people’s desperate yearning for cultural survival and a world free from oppression. It also serves as a chilling indictment of a government’s failure to understand, its propensity to fear, and its willingness to violently suppress a spiritual movement it perceived as a threat. The whispers of the Ghost Dance, though silenced by cannon fire and rifle shots, continue to echo, urging us to remember the tragic reckoning at Wounded Knee and to confront the enduring legacy of injustice that shaped a nation.