The Unsettling Truth: The Indian Removal Act of 1830 and America’s Stain of Dispossession

On May 28, 1830, President Andrew Jackson affixed his signature to the Indian Removal Act, a legislative maneuver that would indelibly scar the fabric of the young American republic. Far from an isolated incident, this act was the culmination of decades of escalating tensions, racial prejudices, land hunger, and a profound ideological clash over the very definition of American nationhood. It represented a pivotal moment where the nation’s stated ideals of liberty and justice were starkly contradicted by its actions, setting in motion a tragic displacement that reverberates through history as the Trail of Tears.

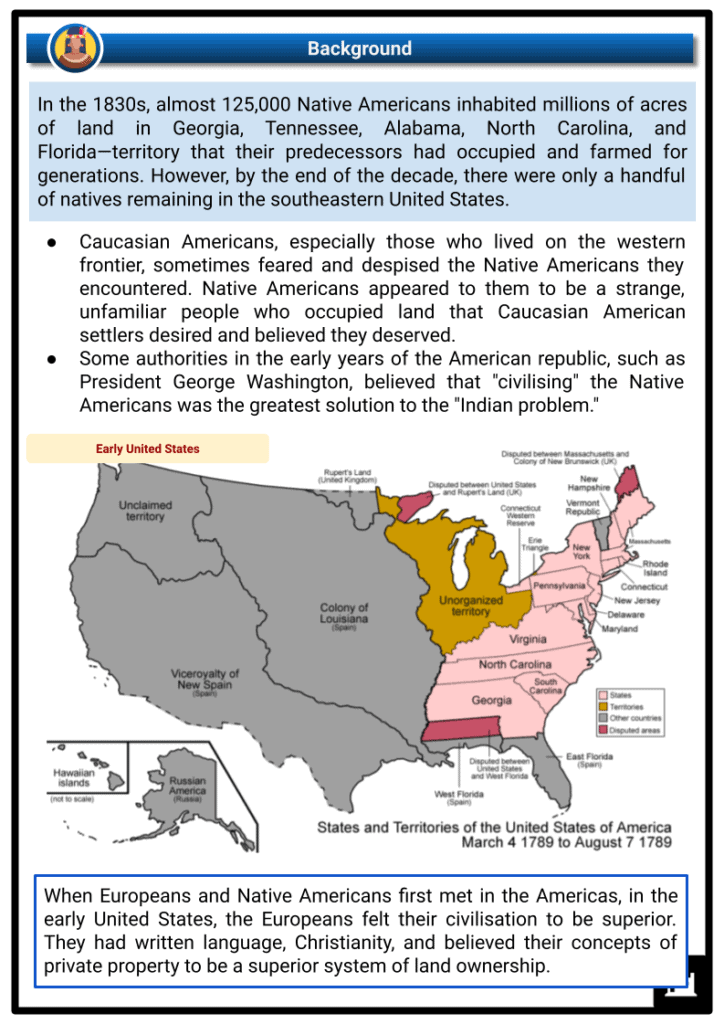

To comprehend the full weight of the Indian Removal Act, one must delve into the sprawling historical context that preceded it. The early 19th century was a period of fervent westward expansion for the United States. The Louisiana Purchase of 1803 had doubled the nation’s size, fueling an insatiable demand for land, particularly in the burgeoning "Cotton Kingdom" of the South. The invention of the cotton gin had transformed the Southern economy, making cotton king and driving the need for vast tracts of land for plantations. These lands, however, were not empty; they were the ancestral homes of numerous Native American nations.

Among the most prominent were the "Five Civilized Tribes" – the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole. These nations, particularly the Cherokee, had made remarkable strides in assimilating into Anglo-American society, a strategy often encouraged by earlier U.S. administrations as a means of "civilizing" them. The Cherokee, in particular, had adopted many aspects of American culture: they established a written constitution modeled on that of the U.S., developed a sophisticated legal system, embraced settled agriculture, built schools, and even owned African slaves. Sequoyah’s invention of a written syllabary in 1821 brought widespread literacy to the Cherokee Nation, allowing them to publish their own newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix. They were, by any measurable standard, a sovereign and self-govergoverning people, often more "civilized" in the European sense than some of their white neighbors.

Despite these efforts at assimilation, or perhaps because of them, their very success became an impediment to white expansion. Their rich agricultural lands in Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi were coveted. The discovery of gold in Cherokee territory in Dahlonega, Georgia, in 1829, only intensified the pressure, sparking a gold rush that brought thousands of white prospectors onto Cherokee lands and further inflamed the land-hungry state.

Georgia, a state with a long-standing claim to much of the Cherokee land, became the primary antagonist in this unfolding drama. The state government aggressively asserted its jurisdiction over Cherokee territory, nullifying their laws, harassing their citizens, and refusing to recognize their sovereignty. This created a profound constitutional crisis, pitting state’s rights against federal treaty obligations. Since the formation of the republic, the U.S. government had consistently negotiated treaties with Native American nations as foreign powers, implicitly recognizing their sovereignty. However, Georgia’s actions, coupled with the prevailing racial attitudes of the time, began to chip away at this foundational principle.

Enter Andrew Jackson. A military hero renowned for his victories against Native American tribes (Creek War) and the British (Battle of New Orleans), Jackson held a deep-seated, if paternalistic, view of Native Americans as "savages" incapable of self-governance and destined to give way to white civilization. He genuinely believed that removal was a "benevolent policy" that would save Native Americans from extinction, allowing them to prosper in a new territory away from the corrupting influence of white society. He argued that it was a necessary step for national security and economic progress. In his Second Annual Message to Congress in December 1830, Jackson articulated his vision: "It will separate the Indians from immediate contact with settlements of whites; free them from the power of the States; enable them to pursue happiness in their own way and under their own rude institutions; will retard the progress of decay, which is lessening their numbers, and perhaps cause them gradually, under the protection of the Government and through the influence of good counsels, to cast off their savage habits and become an interesting, civilized, and Christian community."

Jackson’s stance was immensely popular among white Southerners and many across the nation who shared his expansionist vision and racial prejudices. However, it was not without significant opposition. Northeastern religious groups, some members of Congress (including figures like Davy Crockett, who famously stated, "I will not go to Congress and vote away the rights of these people"), and even some prominent women’s groups petitioned against the Act, citing moral and ethical objections. They argued that forced removal violated natural law, Christian principles, and the nation’s own treaty obligations.

The Cherokee Nation, led by Principal Chief John Ross, did not passively accept their fate. They pursued a strategy of legal resistance, taking their case to the highest court in the land. In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), the Supreme Court, under Chief Justice John Marshall, ruled that the Cherokee Nation was not a foreign state but a "domestic dependent nation" and thus could not sue in federal court. While a setback, it laid the groundwork for a more definitive ruling.

The following year, in Worcester v. Georgia (1832), the Supreme Court delivered a landmark decision. Samuel Worcester, a white missionary living among the Cherokee and defying Georgia’s laws, was arrested. Marshall’s Court sided with Worcester, declaring that the laws of Georgia had no force within Cherokee territory and that the Cherokee Nation was a distinct political community with territorial boundaries within which "the laws of Georgia can have no force." This was a clear victory for the Cherokee and a powerful rebuke to Georgia’s aggressive policies.

However, Jackson famously defied the Supreme Court’s ruling. Legend has it that he declared, "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it." Whether he uttered these exact words or not, his actions certainly reflected this sentiment. He refused to intervene to protect the Cherokee, effectively siding with Georgia and undermining the authority of the judicial branch. This act of executive defiance set a dangerous precedent and rendered the Supreme Court’s decision largely meaningless in practice.

With the federal government refusing to enforce the Supreme Court’s ruling, the stage was set for the tragic implementation of the Indian Removal Act. While some tribes, like the Choctaw, signed treaties under duress and were removed relatively early, the Cherokee continued to resist. A small, unauthorized faction of the Cherokee, known as the Treaty Party and led by Elias Boudinot and Major Ridge, signed the Treaty of New Echota in 1835, ceding all Cherokee lands east of the Mississippi in exchange for five million dollars and land in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). The vast majority of the Cherokee Nation, represented by Chief John Ross, vehemently rejected this treaty, arguing that the Treaty Party had no authority to speak for the nation.

Despite the overwhelming opposition of the Cherokee people, the U.S. Senate ratified the fraudulent Treaty of New Echota by a single vote. When the deadline for voluntary removal passed in May 1838, President Martin Van Buren, Jackson’s successor, ordered the U.S. Army, under General Winfield Scott, to forcibly remove the remaining 16,000 Cherokees.

What followed was one of the darkest chapters in American history: the Trail of Tears. The Cherokees were rounded up at bayonet point, often with little more than the clothes on their backs, and herded into stockades. From there, they were forced to march some 1,200 miles west, mostly on foot, during the brutal winter of 1838-1839. Lacking adequate food, water, and shelter, and exposed to disease, an estimated 4,000 of the 16,000 Cherokees died along the way – a quarter of their population. Women, children, and the elderly were particularly vulnerable. Eyewitness accounts speak of unimaginable suffering, widespread illness, and the desecration of sacred lands.

The Indian Removal Act of 1830, and the subsequent forced removals of the Five Civilized Tribes and others, profoundly reshaped the American continent and its relationship with its indigenous peoples. It solidified the notion of Manifest Destiny, paving the way for further territorial expansion and the subjugation of Native American sovereignty. The Act established a precedent for the federal government’s policy of relocation and assimilation, leading to centuries of broken treaties and systemic injustices.

The legacy of the Indian Removal Act is a complex and enduring one. It represents a betrayal of foundational American ideals and a stark reminder of the devastating consequences when economic greed and racial prejudice override justice and humanitarian concerns. The Trail of Tears is not merely a historical event; it is a profound wound in the nation’s collective memory, a testament to the resilience of Native American peoples, and a critical lesson in the ongoing struggle for human rights and self-determination. The historical context surrounding this act compels us to confront the uncomfortable truths of our past and understand how these pivotal decisions continue to shape the present.