A Dialogue of Dispossession: The Enduring Challenges of Native American Diplomacy

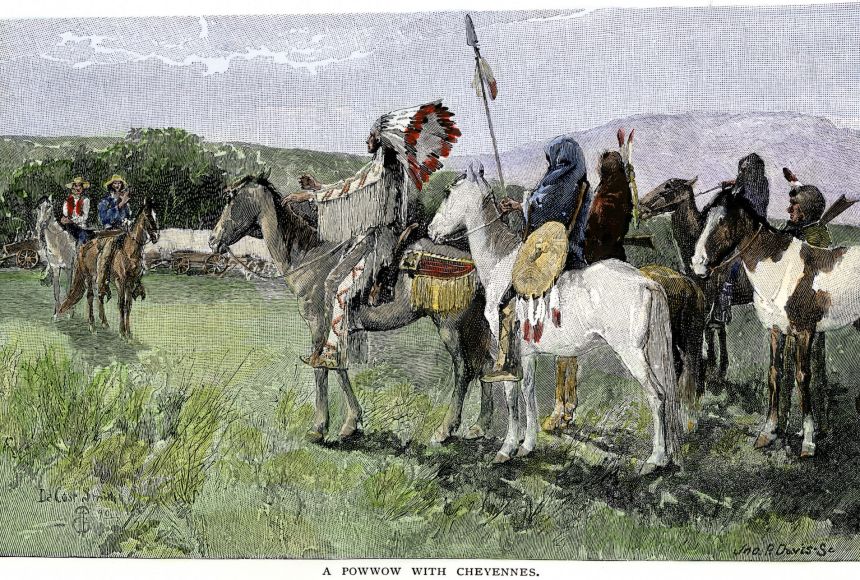

From the moment the first European ships touched the shores of the Americas, a complex and often tragic diplomatic dance began. For Indigenous nations, this was not a new practice; sophisticated systems of governance, alliance-building, and conflict resolution had flourished across the continent for millennia. However, the arrival of European powers, and later the nascent United States, introduced a fundamentally alien set of assumptions, ambitions, and power dynamics that would forever reshape Native American diplomacy, presenting a series of formidable and often insurmountable challenges.

The struggle was not merely one of military might, but a profound clash of worldviews, legal systems, and aspirations. Native American nations sought to preserve their sovereignty, lands, and ways of life through negotiation and alliance, often against an adversary that increasingly viewed their very existence as an impediment to progress and expansion. The story of Native American diplomacy is, therefore, a testament to extraordinary resilience and strategic acumen, but also a poignant chronicle of misunderstanding, betrayal, and ultimately, dispossession.

The Cultural Chasm: A Dialogue of the Deaf

Perhaps the most fundamental challenge lay in the vast cultural chasm separating Indigenous and European societies. Concepts central to European diplomacy – such as individual land ownership, centralized hierarchical government, and written treaties as immutable legal documents – often had no direct equivalent in Native American cultures.

For many Indigenous peoples, land was not a commodity to be bought, sold, or "owned" in the European sense, but a sacred relative, a source of sustenance, and a communal trust. As the attributed words of Chief Seattle famously convey, though the exact wording is debated, the sentiment resonates: "How can you buy or sell the sky, the warmth of the land? The idea is strange to us." European negotiators, however, operated under a paradigm where land could be acquired and boundaries definitively drawn, leading to profound misunderstandings about the permanence and scope of land cessions.

Governance structures also differed dramatically. European powers often sought to negotiate with a single "chief" or "king," assuming a centralized authority that rarely existed in the diverse Indigenous political landscape. Many Native nations operated through consensus-based decision-making, with councils, clan mothers, and spiritual leaders holding significant influence. A "chief" might have limited authority, acting more as a spokesperson than an absolute ruler, and agreements required the widespread consent of the people. This often led to Europeans negotiating with individuals who lacked the authority to bind their entire nation, only for those agreements to be later repudiated by the community, viewed by Europeans as duplicity rather than a difference in political structure.

Language barriers compounded these issues. Even with interpreters, conceptual differences were often impossible to bridge. Words like "sovereignty," "title," or "cession" carried distinct meanings, leading to agreements that were understood one way by Native signatories and quite another by European powers. A "peace" treaty might mean an end to hostilities and a return to normal relations for one side, while for the other, it implied submission and territorial concession.

The Imbalance of Power: Disease, Demographics, and Destructive Technologies

From the outset, the diplomatic playing field was drastically uneven, heavily tilted by the introduction of European diseases, superior weaponry, and overwhelming demographic pressure. Indigenous populations, lacking immunity to illnesses like smallpox, measles, and influenza, were decimated upon contact. Estimates suggest that up to 90% of some Native communities perished in the centuries following European arrival. This catastrophic demographic collapse weakened nations, disrupted social structures, and left them vulnerable long before formal negotiations even began. A nation ravaged by disease was less able to field warriors, maintain internal cohesion, or present a united front in diplomatic encounters.

European firearms, while not always decisive, provided a significant military advantage, particularly in the early encounters. More importantly, the relentless tide of European immigration meant an ever-growing demand for land. This demographic pressure fueled a relentless expansionist agenda, making any "permanent" diplomatic solution inherently unstable from the Native perspective. The concept of Manifest Destiny – the belief in America’s divinely ordained right to expand across the continent – became a powerful ideological driver that undermined any notion of respecting Native sovereignty or territorial integrity.

Internal Divisions and External Exploitation

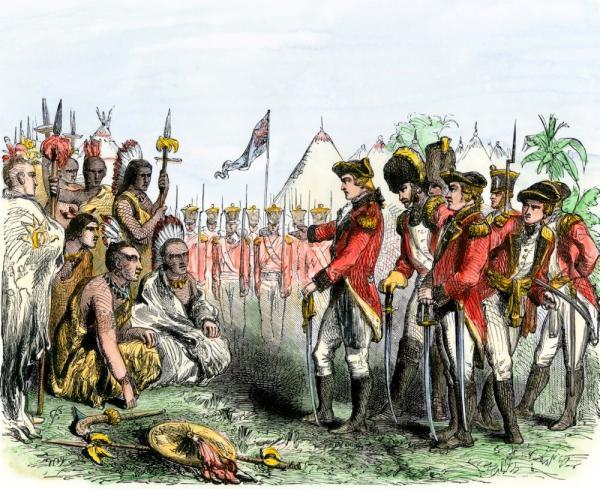

Native American nations were not monolithic. Pre-existing rivalries, alliances, and historical grievances were a feature of the continent long before Europeans arrived. Colonial powers, and later the United States, expertly exploited these divisions, often playing one nation against another to achieve their own objectives. During the French and Indian War, the American Revolution, and the War of 1812, both European and American forces actively sought Native allies, promising protection and territory in exchange for military support. These alliances, while sometimes offering temporary advantages, often led to further fragmentation and vulnerability for Indigenous peoples.

For example, the Iroquois Confederacy, a powerful and sophisticated political entity, was ultimately divided by the American Revolution, with some nations siding with the British and others with the Americans, a split that had lasting and damaging consequences for their collective power and diplomatic unity. This tactic of "divide and conquer" was a persistent challenge, making it exceedingly difficult for Native nations to present a united front against a common adversary.

The Ephemeral Nature of Treaties: Broken Promises and Shifting Policies

Perhaps the most enduring and bitter challenge for Native American diplomacy was the systemic failure of European and American powers to honor their treaty obligations. Over 500 treaties were signed between the U.S. government and various Native American nations, almost all of which were eventually broken or reinterpreted to the detriment of Indigenous peoples.

For Native nations, a treaty was often a sacred covenant, a binding agreement forged in good faith. For the U.S. government, treaties increasingly became expedient tools to acquire land, manage "Indian affairs," and facilitate westward expansion. As the balance of power shifted decisively in favor of the United States, treaties were often seen as temporary measures, subject to renegotiation, unilateral abrogation, or simply ignored.

The infamous Indian Removal Act of 1830, championed by President Andrew Jackson, epitomized this disregard. Despite Supreme Court rulings like Worcester v. Georgia (1832), which affirmed Cherokee sovereignty and condemned Georgia’s actions, Jackson famously defied the ruling, reportedly stating, "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it!" This executive defiance paved the way for the forced removal of the Cherokee and other Southeastern nations along the "Trail of Tears," a horrific demonstration that even judicially affirmed treaty rights offered no protection against governmental will and land hunger.

The policy pendulum swung repeatedly: from treaty-making to removal, then to the reservation system, followed by the assimilation-focused policies of the Dawes Act (allotment), the "termination" era, and finally, the era of self-determination in the late 20th century. Each shift introduced new diplomatic challenges, often erasing previous gains and requiring Native nations to constantly adapt and re-litigate their rights.

The Legal Labyrinth and the Erosion of Sovereignty

The American legal system, while theoretically offering a framework for resolving disputes, often became another tool for undermining Native sovereignty. The landmark Supreme Court cases of the 1830s, particularly Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831) and Worcester v. Georgia (1832), defined Native nations as "domestic dependent nations" – a status that, while acknowledging a unique political existence, simultaneously curtailed their full sovereignty. Chief Justice John Marshall, in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, described them as "wards to their guardian," a paternalistic framing that denied them full international recognition and subjected them to the plenary power of the U.S. Congress.

This legal framework meant that Native nations could not appeal to international law or foreign powers for protection against U.S. actions. Their only recourse was often through the very legal system of the nation that was actively dispossessing them, a system that frequently prioritized federal interests over Indigenous rights. The concept of "plenary power" allowed Congress broad authority over "Indian affairs," often enabling unilateral actions that abrogated treaties, redefined boundaries, and dictated internal governance, leaving Native nations with little leverage in diplomatic negotiations.

The Enduring Legacy and Modern Challenges

The challenges of Native American diplomacy are not confined to the past. The legacy of broken treaties, forced assimilation, and the erosion of sovereignty continues to shape the contemporary landscape. Modern Native American nations still grapple with issues stemming from historical injustices: land claims, water rights, resource management, the preservation of cultural heritage, and the ongoing struggle for true self-determination.

Today, Native American diplomacy primarily occurs within the framework of federal-tribal relations, advocating for treaty rights, seeking economic development, and asserting their inherent sovereignty. While the era of overt military conquest is over, the challenges persist in more subtle forms: navigating complex legal battles, confronting stereotypes, securing adequate funding for essential services, and resisting continued encroachments on their lands and cultures.

The history of Native American diplomacy is a powerful reminder of the profound human cost when distinct cultures collide, when power is wielded without justice, and when promises are made only to be broken. It is a story of immense difficulty, but also of incredible resilience, as Indigenous nations continue to assert their rights and identities, demonstrating a profound commitment to their ancestral lands and sovereign futures.