The Great Silence: A History of Native American Population Decline

The story of the Americas is often told as one of discovery, settlement, and the relentless march of progress. Yet, beneath this triumphant narrative lies a far darker truth: a demographic catastrophe of unparalleled scale, the systematic decimation of the Native American population. From an estimated tens of millions thriving across two continents before European contact, their numbers plummeted to a mere fraction, a decline driven by a brutal cocktail of disease, warfare, displacement, and deliberate policies of cultural annihilation. This is the history of the Great Silence, a testament to immense loss and, ultimately, enduring resilience.

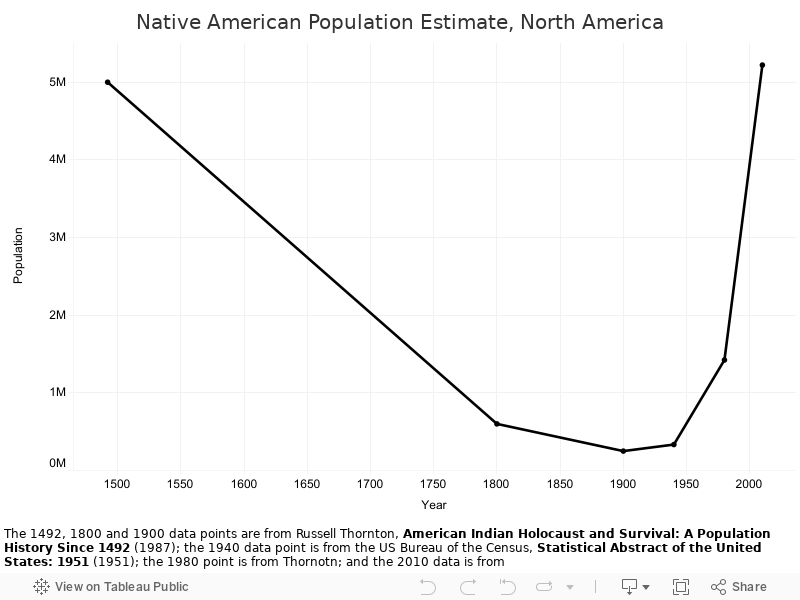

Before 1492, the Americas were not an empty wilderness awaiting European settlement, but a vibrant tapestry of diverse cultures, complex societies, and sophisticated agricultural systems. Estimates of the pre-Columbian population vary widely, but scholarly consensus suggests figures ranging from 50 to 100 million across the hemisphere, with North America alone potentially home to 7-18 million people. These were not primitive hunter-gatherers, but farmers, astronomers, architects, and spiritualists who had shaped their landscapes for millennia. Their societies ranged from the vast empires of the Inca and Aztec to the sophisticated mound-building cultures of the Mississippi Valley and the intricate kinship networks of the Pacific Northwest.

The arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1492 marked the beginning of the end for this flourishing world. While often romanticized, his voyages initiated a biological and cultural exchange that was overwhelmingly devastating for the indigenous inhabitants. European explorers and settlers inadvertently, and sometimes intentionally, introduced a host of diseases against which Native Americans had no immunity: smallpox, measles, influenza, typhus, and bubonic plague. These "virgin soil epidemics" swept through communities with terrifying speed and lethality.

Within decades, entire nations were decimated. The Taíno people of Hispaniola, who greeted Columbus, saw their population of several hundred thousand reduced to mere thousands within a generation. As Jared Diamond vividly describes in Guns, Germs, and Steel, "The most potent weapon in the European arsenal was disease." Estimates suggest that 90-95% of the indigenous population perished in the first century and a half after contact, a demographic collapse unprecedented in human history. Entire societies vanished, their languages and traditions lost, leaving behind a silence that spoke volumes of the devastation.

While disease was the primary killer in the initial centuries, the relentless pursuit of land, resources, and dominion by European colonists soon introduced another potent factor: systematic violence and warfare. As colonial settlements expanded, clashes over territory became inevitable. Early conflicts like the Pequot War (1636-1638) in New England set a brutal precedent, with English colonists, aided by rival Native American tribes, massacring hundreds of Pequot in a fortified village, effectively wiping out the tribe as a political entity.

The rhetoric of the time often dehumanized Native Americans, portraying them as "savages" or obstacles to "civilization," justifying their displacement and extermination. Scalping bounties, first introduced by the Dutch and later adopted by the English, incentivized the killing of indigenous people. Benjamin Franklin, a revered Founding Father, once suggested that rum could be used to "extirpate" the Native population, reflecting a widespread sentiment that saw indigenous peoples as an impediment to progress rather than as fellow human beings.

The establishment of the United States did little to alleviate the pressure. With the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 and the doctrine of Manifest Destiny taking hold, the young nation set its sights on westward expansion, viewing Native American lands as rightfully theirs. This era ushered in the most infamous period of forced removal. President Andrew Jackson, a veteran of numerous wars against Native Americans, championed the Indian Removal Act of 1830. This legislation authorized the forced relocation of thousands of Southeastern Native Americans – the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole – from their ancestral lands to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma).

The most tragic outcome of this policy was the Cherokee’s "Trail of Tears" in 1838. Despite a Supreme Court ruling in Worcester v. Georgia (1832) that affirmed Cherokee sovereignty, Jackson famously defied the decision, stating, "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it." Over 16,000 Cherokee were forcibly marched over a thousand miles, often in brutal winter conditions, with inadequate food and shelter. An estimated 4,000 men, women, and children died from disease, starvation, and exposure, their suffering etched into the national memory as a profound act of injustice.

As settlers pushed further west, the Plains Indians faced a new wave of encroachment. The mid-to-late 19th century was characterized by the brutal "Indian Wars," a series of conflicts between various Plains tribes and the U.S. Army. Battles like Sand Creek (1864), where Colorado militia massacred hundreds of Cheyenne and Arapaho, mostly women, children, and the elderly, and the Battle of Little Bighorn (1876), where Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors annihilated Custer’s 7th Cavalry, became iconic symbols of this bloody era.

Beyond direct military engagement, the U.S. government employed a devastating strategy against the Plains tribes: the extermination of the American bison. The buffalo was central to the Plains Indians’ way of life, providing food, shelter, clothing, and spiritual sustenance. By the late 19th century, millions of bison had been slaughtered, often for sport or to clear the way for railroads, but also as a deliberate military tactic to starve the Native population into submission. "Kill every buffalo you can," advised Colonel Richard Irving Dodge, "Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone." This policy proved devastatingly effective, forcing many tribes onto reservations.

The reservation system, established by treaties often broken by the U.S. government, confined Native Americans to small, often barren tracts of land, severing their connection to traditional hunting grounds and sacred sites. Life on reservations was marked by poverty, disease, malnutrition, and a profound loss of autonomy. The final massacre of the Indian Wars occurred at Wounded Knee in 1890, where U.S. troops killed an estimated 300 unarmed Lakota men, women, and children, ending an era of open resistance and marking the nadir of Native American population decline.

The turn of the 20th century saw the Native American population reach its lowest point, estimated at around 250,000 in the U.S. from millions just four centuries prior. Yet, the assault on Native American identity did not cease. The focus shifted from physical extermination to cultural assimilation, epitomized by the Dawes Act of 1887 and the boarding school system. The Dawes Act aimed to break up tribal communal landholdings into individual allotments, intending to transform Native Americans into yeoman farmers and integrate them into American society. The result was further massive land loss, as "surplus" lands were sold off to non-Native settlers, and individual allotments were often quickly lost through fraud or economic hardship.

Perhaps the most insidious policy was the forced removal of Native American children to boarding schools. Institutions like the Carlisle Indian Industrial School operated under the philosophy, famously articulated by its founder Richard Henry Pratt, "Kill the Indian, Save the Man." Children as young as five were taken from their families, forbidden to speak their native languages, practice their spiritual traditions, or wear their traditional clothing. Their hair was cut, their names often changed, and they were subjected to harsh discipline, forced labor, and often physical and sexual abuse. The goal was to erase their cultural identity, sever their ties to their heritage, and mold them into "civilized" Americans. The psychological and emotional trauma inflicted by these schools continues to reverberate through generations, contributing to ongoing challenges within Native communities.

Despite this prolonged and multi-faceted assault, Native American peoples have demonstrated extraordinary resilience. The mid-20th century saw the beginning of a slow demographic recovery and a powerful movement for self-determination. The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 finally granted all Native Americans U.S. citizenship, though many had already gained it through military service or other means. The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 sought to reverse some of the Dawes Act’s damage and promote tribal self-governance.

The 1960s and 70s brought renewed activism, leading to landmark legislation like the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975, which allowed tribes greater control over their own affairs and resources. Today, the Native American population in the U.S. is growing, with over 5 million individuals identifying as Native American or Alaska Native, including those of mixed heritage. Tribal nations are actively working to revitalize their languages, cultural practices, and economic sovereignty.

However, the legacy of population decline and historical trauma persists. Native American communities continue to face disproportionate rates of poverty, health disparities, and violence, often stemming directly from centuries of displacement, disease, and cultural suppression. The story of Native American population decline is not merely a historical footnote; it is a profound and ongoing narrative of loss, resilience, and the enduring fight for justice and recognition. It serves as a stark reminder of the human cost of colonialism and the imperative to confront the uncomfortable truths of history in the pursuit of a more equitable future.