Echoes in the Code: The Enduring Scars of Colonial Legal Systems on Indigenous Tribes

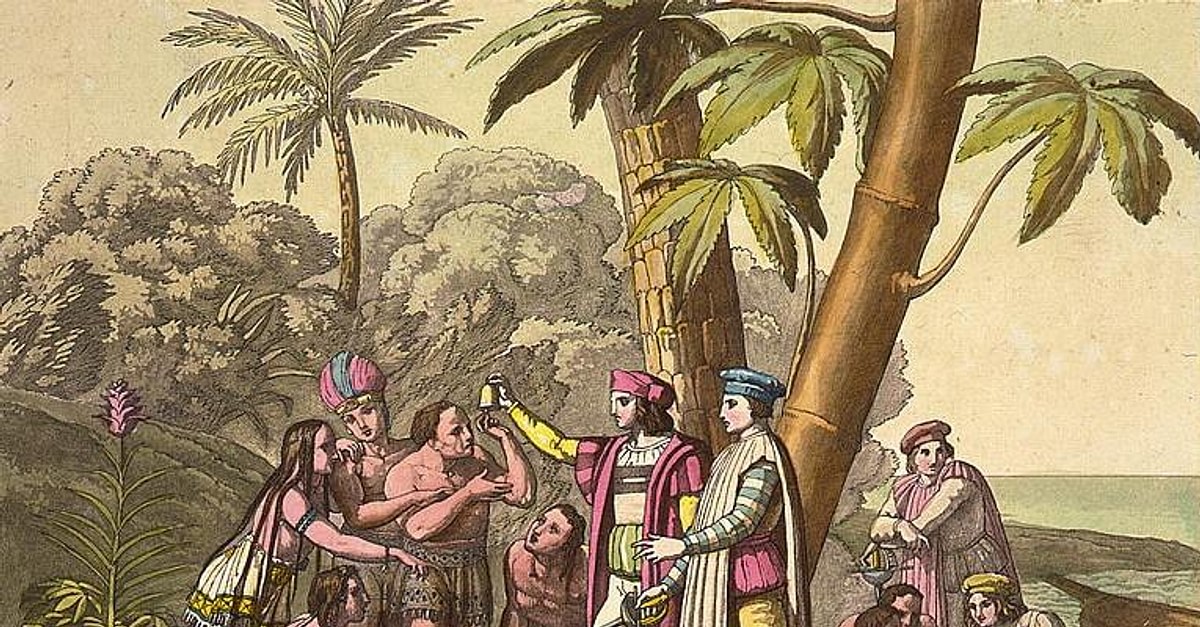

The grandeur of Western legal systems, often lauded as bastions of justice and order, belies a darker chapter in history: their deployment as instruments of subjugation against indigenous tribes across the globe. From the Americas to Australia, Africa to Asia, colonial powers systematically dismantled, suppressed, and replaced pre-existing tribal legal frameworks with their own, leaving behind a complex legacy of land dispossession, cultural erosion, and an enduring struggle for self-determination. This imposition was not merely an administrative act; it was a profound act of legal violence, designed to facilitate control, exploit resources, and reshape entire societies in the image of the colonizer.

Before the advent of colonialism, indigenous legal systems were as diverse and rich as the cultures they served. Often oral, deeply intertwined with spiritual beliefs, and rooted in communal well-being and restorative justice, these systems governed everything from land use and resource allocation to dispute resolution and social order. Land, for many tribes, was not a commodity to be owned individually but a living entity, held in stewardship for future generations. Justice often focused on healing relationships and restoring balance, rather than purely punitive measures. As Professor Robert A. Williams Jr. notes in his seminal work, "The American Indian in Western Legal Thought," these pre-existing systems represented sophisticated forms of governance, largely ignored or actively denigrated by incoming European powers.

The colonial project, however, demanded a different kind of order. European legal traditions – primarily common law (British) and civil law (French, Spanish, Portuguese) – were fundamentally incompatible with indigenous worldviews. Concepts like individual property rights, state sovereignty, and a hierarchical court system stood in stark contrast to communal ownership, tribal self-governance, and consensus-based justice.

One of the most devastating impacts of colonial legal systems was on land and resource rights. The European concept of terra nullius – "land belonging to no one" – was a legal fiction employed to justify the seizure of vast territories deemed "unoccupied" or "undeveloped" according to European standards, despite being home to thriving indigenous communities for millennia. This doctrine was famously applied in Australia, where it was only overturned in the landmark 1992 Mabo v Queensland (No 2) High Court decision, which recognized the pre-existence of native title. As Justice Brennan stated in the Mabo judgment, "The fiction by which the rights and interests of indigenous inhabitants in land were treated as non-existent was justified by a policy which has no place in the contemporary law of this country."

Beyond terra nullius, colonial governments enacted a panoply of laws designed to dispossess tribes of their ancestral lands. In the United States, the General Allotment Act (Dawes Act) of 1887 broke up communally held tribal lands into individual plots, with the "surplus" then sold off to non-Native settlers. This policy fragmented tribal territories, destroyed traditional land management practices, and drastically reduced the land base of many Native American nations. Similarly, in Canada, the Indian Act of 1876, a sprawling and paternalistic piece of legislation, exerted immense control over nearly every aspect of Indigenous life, including land management, governance, and cultural practices, effectively treating First Nations as wards of the state.

The imposition of colonial legal systems also profoundly undermined indigenous governance and sovereignty. Traditional leadership structures, often based on hereditary lines, spiritual authority, or community consensus, were systematically dismantled or co-opted. Colonial powers frequently installed "chiefs" or "headmen" who were loyal to the colonial administration, regardless of their legitimacy within the tribal community. This "indirect rule," particularly prevalent in British Africa, created a dual system where statutory law coexisted with, but ultimately superseded, customary law, leading to confusion, internal divisions, and a significant weakening of tribal authority. The authority to make and enforce laws, once inherent to tribal nations, was transferred to the colonial state, reducing tribes to mere administrative units.

Furthermore, colonial legal systems were instrumental in the erosion of cultural identity and social cohesion. Laws were often used to criminalize traditional practices, languages, and spiritual ceremonies. For example, in both Canada and the United States, residential schools (often mandated by law and operated by churches) forcibly removed Indigenous children from their families, banning their languages and cultural practices in a deliberate attempt to "kill the Indian in the child." The legal framework that enabled these institutions inflicted intergenerational trauma that continues to impact Indigenous communities today. The suppression of customary laws regarding marriage, family structures, and inheritance also destabilized traditional social orders, leading to the breakdown of kinship networks and community support systems.

The impact extended to justice and human rights, where indigenous individuals often faced a double standard in colonial courts. Their traditional forms of dispute resolution were dismissed as primitive, while they were subjected to foreign judicial processes that often lacked cultural understanding or due process. Punishments under colonial law were frequently harsher for indigenous people, and their testimonies or customary evidence were often devalued. This created a profound sense of injustice and alienation from the very systems purporting to bring "civilization."

The Enduring Legacy and the Path Forward

The colonial legal systems’ legacy is not confined to history books; it continues to manifest in contemporary legal battles, socio-economic disparities, and ongoing struggles for recognition and self-determination. Indigenous communities today grapple with the consequences of fragmented land bases, jurisdictional complexities, and the intergenerational trauma wrought by assimilationist policies.

However, the story is not one of absolute defeat. Indigenous peoples have consistently resisted these impositions, often through legal means. The Mabo decision in Australia, the ongoing land claims and treaty rights litigation in North America, and constitutional provisions recognizing customary law in various African nations are testaments to this enduring struggle. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), adopted in 2007, represents a crucial international framework affirming the collective and individual rights of Indigenous peoples, including their rights to self-determination, lands, territories, resources, and to maintain and strengthen their distinct legal, political, economic, social and cultural institutions.

The call for legal pluralism – the recognition and integration of customary law within national legal frameworks – is gaining traction. This is not about returning to a pre-colonial past, but about fostering legal systems that are more just, inclusive, and reflective of the diverse societies they serve. It involves understanding that indigenous legal systems offer valuable perspectives on restorative justice, environmental stewardship, and community governance that can enrich broader legal traditions.

In conclusion, the impact of colonial legal systems on indigenous tribes has been profound and devastating, serving as a primary mechanism for disempowerment, dispossession, and cultural destruction. They systematically dismantled existing legal orders, imposed alien concepts, and created enduring injustices. Yet, the resilience of indigenous peoples, their unwavering commitment to their distinct legal traditions, and their persistent advocacy on national and international stages offer a beacon of hope. The ongoing journey towards reconciliation and true justice demands a critical re-evaluation of these historical impositions and a concerted effort to build legal frameworks that respect, protect, and empower the inherent rights and unique contributions of indigenous nations. Only then can the echoes of colonial codes truly begin to fade, replaced by a symphony of diverse and equitable legal voices.