Echoes of Erasure: How Colonial Education Forged Generational Trauma in Indigenous Children

The classroom, often envisioned as a sanctuary of learning and growth, became a crucible of cultural destruction for millions of Indigenous children worldwide under the pervasive shadow of colonial rule. From the residential schools of Canada and the United States to the mission schools of Australia and Africa, these institutions were not merely places of academic instruction; they were deliberate instruments of assimilation, designed to dismantle Indigenous identities, languages, and spiritualties. The impact of this systematic "education" was nothing short of devastating, inflicting wounds that festered across generations, leaving an indelible legacy of trauma, cultural dislocation, and an enduring struggle for healing and reclamation.

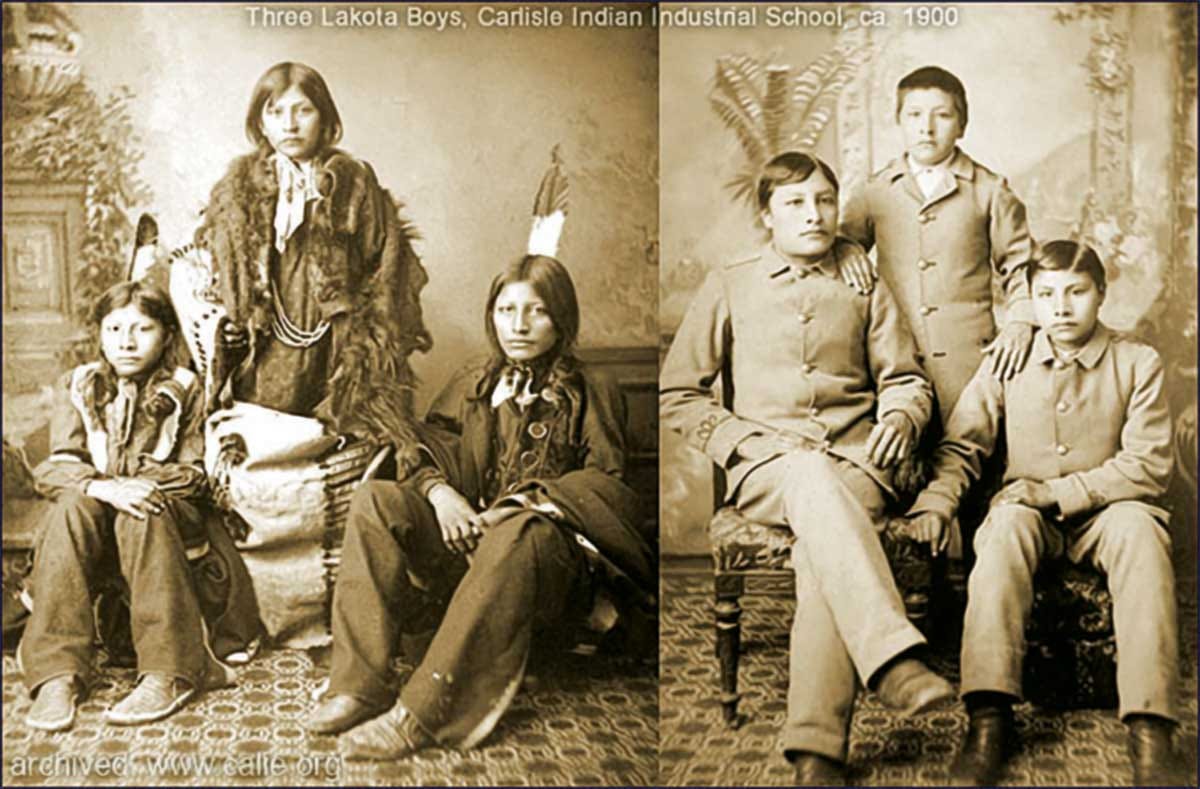

At the heart of colonial education lay a chillingly explicit philosophy: to "kill the Indian in the child," as articulated by Captain Richard Henry Pratt, founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in the United States. This ideology, echoed in various forms across colonial powers, posited Indigenous cultures as inherently inferior, savage, and an impediment to "progress." The goal was not to educate Indigenous children to thrive within their own societies, but to forcibly strip them of their heritage and remold them into a subservient class compatible with the colonizers’ economic and social structures. This mission was often spearheaded by religious organizations, who, armed with evangelical fervor and government funding, believed they were "saving" Indigenous souls from paganism.

The first step in this process was the forced removal of children from their families and communities. Often as young as four or five, children were forcibly taken, sometimes by police or agents, from their parents, who faced severe penalties for resistance. This initial act of separation was a profound trauma, severing the fundamental bonds of love, security, and belonging that are crucial for a child’s development. Parents were left heartbroken and powerless, while children were plunged into an alien and often hostile environment, deprived of the comfort of their language, their traditional foods, and the familiar embrace of their loved ones. As one survivor from Canada’s residential school system recounted, "They came and took us. My mother tried to hide me, but they found me. I was just a small boy, and I never saw her again for years."

Upon arrival at these institutions, children were subjected to a brutal regimen designed to erase their Indigenous identity. Their traditional clothing was confiscated and replaced with uniforms. Their long hair, often culturally significant, was shorn. Most crucially, their native languages were forbidden. Speaking one’s mother tongue, the very vessel of cultural memory and connection, was met with severe punishment – beatings, public humiliation, or even solitary confinement. This linguistic suppression was a direct assault on a child’s ability to communicate, to express their emotions, and to understand the world around them. It created a profound sense of isolation and shame, disconnecting them from their elders and the rich oral traditions that had sustained their communities for millennia.

Beyond the systematic cultural dismantling, the conditions within many colonial schools were abhorrent. Malnutrition was rampant due to inadequate food and poor dietary choices, leading to widespread disease. Tuberculosis, influenza, and other infectious illnesses swept through the dormitories, often with fatal consequences. Medical care was minimal or non-existent, and death rates were alarmingly high. In Canada, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission identified over 4,100 documented deaths in residential schools, though the actual number is believed to be much higher, with unmarked graves still being discovered today. These were not simply schools; they were often places of neglect, suffering, and death.

Perhaps the most insidious and long-lasting impact was the pervasive physical, emotional, and sexual abuse inflicted upon Indigenous children by staff members, many of whom were religious figures. Beatings for minor infractions were common. Emotional abuse, including constant denigration of their culture and identity, chipped away at their self-worth. Sexual abuse, a horrific betrayal of trust, was tragically widespread, leaving deep psychological scars. These abuses were often covered up, and perpetrators rarely faced justice. The schools, intended to "civilize," instead became breeding grounds for trauma, fear, and a profound sense of powerlessness.

The cumulative effect of these experiences was an identity crisis of immense proportions. Children raised in these schools were denied the opportunity to learn traditional skills, spiritual practices, and the complex social structures of their own communities. They were taught to despise their heritage. Yet, they were simultaneously denied full acceptance into the dominant colonial society, often facing racism and discrimination upon leaving the institutions. They became "people in between," alienated from both worlds, struggling to find a sense of belonging or purpose. This dislocated identity contributed to feelings of shame, anger, and a deep sense of loss.

This trauma, however, did not end when the children left the schools. It became intergenerational, a silent but potent force shaping the lives of their descendants. Survivors often struggled with mental health issues such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety, and substance abuse as a means of coping with their pain. Having been denied nurturing and healthy familial models, many found it difficult to form loving relationships or parent their own children, inadvertently perpetuating cycles of dysfunction. The breakdown of traditional family structures and parenting practices, directly attributable to the residential school experience, led to further social challenges within Indigenous communities, including higher rates of family violence, suicide, and incarceration.

The Meriam Report of 1928 in the United States, a landmark study, starkly criticized the conditions and philosophy of Indian boarding schools, concluding that their primary goal of assimilation was failing and causing immense harm. In Australia, the "Stolen Generations" refers to the generations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children who were forcibly removed from their families by government agencies and church missions. The 1997 "Bringing Them Home" report documented the profound and lasting harm caused by these policies, describing it as a "cultural genocide." These reports, alongside the Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s findings, underscore the global consensus on the catastrophic failure and ethical bankruptcy of colonial education.

Despite the profound damage, the story of Indigenous children and colonial education is also one of immense resilience and resistance. Many survivors, against all odds, found ways to heal and rebuild their lives. Indigenous communities today are engaged in vital work to reclaim their languages, revitalize their cultures, and restore the traditional knowledge systems that were suppressed. Language immersion programs, cultural camps, and Indigenous-led education initiatives are powerful acts of defiance and self-determination, aimed at mending the severed connections and empowering future generations.

The ongoing process of truth and reconciliation, particularly prominent in Canada, involves acknowledging the historical injustices, documenting the experiences of survivors, and working towards meaningful apologies and reparations. While financial compensation is a necessary step, the deeper healing requires a fundamental shift in societal understanding, a commitment to decolonization, and genuine respect for Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination.

In conclusion, colonial education’s impact on Indigenous children was a deliberate, systematic, and profoundly damaging campaign of cultural genocide. It severed family bonds, suppressed languages, inflicted widespread abuse, and created an enduring legacy of intergenerational trauma that continues to affect Indigenous communities today. Understanding this dark chapter is not merely an act of historical remembrance; it is an essential step towards recognizing the resilience of Indigenous peoples, supporting their ongoing efforts at reclamation and healing, and ensuring that such egregious injustices are never repeated. The echoes of erasure still resonate, but so too do the powerful voices of survival, truth, and the unwavering spirit of Indigenous identity.