The Unseen Armor: A History of Disease Resistance in Indigenous Populations

The narrative of indigenous populations facing European diseases is often one of unmitigated catastrophe, a tragic testament to the devastating impact of "virgin soil epidemics." From the chilling accounts of smallpox sweeping through the Americas to the relentless march of tuberculosis across the Arctic, the historical record paints a grim picture of communities decimated, cultures fractured, and ancient ways of life irrevocably altered. Yet, beneath this tragic veneer lies a complex, often overlooked history of adaptation, survival, and the profound, albeit sometimes slow, evolution of disease resistance within these very populations.

This is not a story of inherent immunity, but rather one of dynamic interaction between humans, pathogens, and environments – a story that highlights the incredible power of natural selection and the resilience of human biology, even in the face of unprecedented biological assault. To understand this, we must first rewind to the pre-contact world.

Before the Storm: A Different Disease Landscape

Prior to the arrival of Europeans, indigenous populations across the globe, particularly in the Americas and Australia, lived in distinct epidemiological environments. The Americas, for instance, had fewer domesticated animals compared to Eurasia, significantly reducing the pool of zoonotic diseases that could jump to humans. Population densities were generally lower, and travel between distinct cultural groups was often less frequent or extensive than the vast trade networks of the Old World.

Consequently, while indigenous peoples certainly experienced infectious diseases – including various forms of influenza, hepatitis, parasitic infections, and some bacterial illnesses – they lacked exposure to the highly virulent crowd diseases that had plagued Eurasia and Africa for millennia. Smallpox, measles, mumps, rubella, diphtheria, influenza A, and many forms of tuberculosis and malaria were largely absent. Over generations, Old World populations had developed a degree of genetic and acquired immunity to these pathogens, a biological inheritance forged in centuries of devastating epidemics. Indigenous populations, isolated for thousands of years, had no such legacy.

Their health was often robust, supported by diverse diets, active lifestyles, and sophisticated traditional medicinal practices that were highly effective against the pathogens they did encounter. As historian Alfred W. Crosby noted in his seminal work "Ecological Imperialism," the Americas were, in a sense, a "paradise for a variety of germs," but only after the introduction of new hosts.

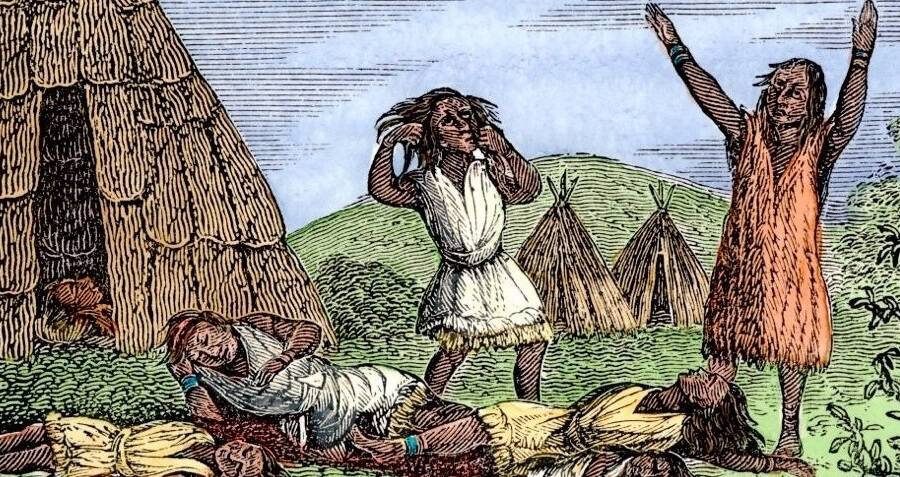

The Cataclysm: Virgin Soil Epidemics and Demographic Collapse

The moment of contact, particularly in the Americas, initiated what historians and epidemiologists term "virgin soil epidemics." When Old World pathogens encountered populations with no prior exposure and thus no natural or acquired immunity, the results were catastrophic. Estimates suggest that between 50% and 90% of indigenous populations in the Americas perished within the first century or two of European contact.

The Florentine Codex, an ethnographic masterpiece compiled by Bernardino de Sahagún in the 16th century, vividly details the horror of smallpox in Tenochtitlan: "Many died of it… Many died of hunger… The pestilence lasted for seventy days… Many died of smallpox, and many others died of hunger, for no one took care of them; others died of thirst, for no one gave them water." This wasn’t merely a health crisis; it was a societal collapse, disrupting social structures, agricultural systems, and spiritual beliefs.

The lack of prior exposure meant not only a biological vulnerability but also a psychological one. Traditional healers, accustomed to treating familiar ailments, found themselves helpless against diseases that swept through entire communities with unprecedented speed and lethality. The scale of death led to profound intergenerational trauma, a wound that continues to impact indigenous communities today.

The Survivors: Natural Selection in Action

Yet, despite the overwhelming devastation, some survived. And in their survival lies the story of nascent disease resistance. Those who possessed even a slight genetic advantage – perhaps a more robust immune response, a unique allele, or a subtle biochemical difference that impeded viral replication – were more likely to live, reproduce, and pass on those advantageous traits to their offspring. This is natural selection in its most brutal and accelerated form.

Over subsequent generations, these selective pressures began to reshape the genetic landscape of indigenous populations. For example, studies have identified specific genetic markers, such as certain HLA (Human Leukocyte Antigen) alleles, that appear to be more prevalent in descendant indigenous populations compared to their pre-contact genetic profiles. HLA genes play a crucial role in immune response, presenting antigens to T-cells to trigger a defense. The increased prevalence of certain HLA types suggests that individuals carrying these variants were more likely to survive specific epidemics and contribute to the gene pool.

Similarly, research into populations that have historically faced specific endemic diseases offers parallels. The Duffy blood group, for instance, is virtually absent in many West African populations, a result of strong natural selection because individuals lacking the Duffy antigen are resistant to Plasmodium vivax malaria. While not directly an indigenous American example, it powerfully illustrates how a pathogen can drive a rapid evolutionary change in a host population.

The process of developing population-wide genetic resistance is not instantaneous; it requires multiple generations of exposure and selective pressure. The scale of the initial depopulation meant that only a fraction of the original genetic diversity remained, creating genetic bottlenecks. However, within these smaller, surviving populations, the genetic traits that conferred even marginal resistance became concentrated.

Beyond Genetics: Environmental and Cultural Resilience

Resistance isn’t solely a matter of genetics. Environmental and cultural factors also played significant, albeit complex, roles in both vulnerability and resilience. Traditional diets, rich in lean proteins, complex carbohydrates, and wild plant nutrients, often offered a stronger baseline of health compared to the nutritionally deficient diets introduced by colonizers. A well-nourished body is better equipped to fight off infection, regardless of genetic predisposition.

Traditional medicinal practices, while overwhelmed by the novelty of Old World diseases, continued to evolve. Healers adapted, incorporating new observations and knowledge. The deep understanding of local flora and fauna, combined with sophisticated spiritual and social support systems, undoubtedly contributed to the survival of individuals and communities. For example, some indigenous groups practiced quarantine for the sick, a rudimentary but effective public health measure.

Furthermore, social structures and community cohesion, though severely strained, could also act as a buffer. Strong kinship ties and collective care practices could ensure that the sick received some level of support, even if a cure was elusive.

Modern Challenges and Shifting Paradigms

In the contemporary era, the health challenges facing indigenous populations have shifted, but the historical legacy of disease and trauma remains. While infectious diseases like smallpox are no longer a threat, many indigenous communities now grapple with disproportionately high rates of chronic diseases such as Type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and certain cancers. These are often linked to forced changes in diet and lifestyle, environmental degradation, and the intergenerational impacts of colonialism, including historical trauma, poverty, and limited access to healthcare.

However, even in the face of these new challenges, the resilience and adaptive capacity observed historically persist. Modern research is exploring how historical selection pressures might influence contemporary disease patterns. For instance, the "thrifty gene hypothesis," though controversial and oversimplified, suggests that genes beneficial for survival during periods of famine (by promoting efficient fat storage) might predispose individuals to diabetes in environments of abundant, high-calorie food. This hypothesis, in some interpretations, has been applied to indigenous populations, though it is critical to acknowledge that socio-economic factors, rather than purely genetic ones, are often the primary drivers of health disparities today.

Contemporary genomic research, often conducted in partnership with indigenous communities, aims to understand the unique genetic profiles and historical adaptations of these populations. This research is not about finding "flaws" but about identifying strengths and vulnerabilities to inform culturally appropriate healthcare strategies. It acknowledges that indigenous populations are not monolithic; immense genetic and cultural diversity exists across and within different groups.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Resilience and a Call for Nuance

The history of disease resistance in indigenous populations is not a simple tale of vulnerability or inherent immunity, but a testament to humanity’s profound capacity for adaptation and survival. It is a story marked by unimaginable loss, but also by the quiet, powerful force of natural selection shaping the very biology of those who endured.

Understanding this history requires moving beyond simplistic narratives of victimhood or exoticism. It demands a nuanced appreciation for the complex interplay of genetics, environment, culture, and colonial history. It highlights the incredible resilience of indigenous peoples, not just in surviving biological assaults, but in maintaining cultural integrity and advocating for their health and well-being in the face of ongoing challenges.

By acknowledging this history of adaptation and the unique biological heritage of indigenous populations, we can foster more respectful, effective, and equitable approaches to health and wellness, ensuring that the lessons learned from centuries of struggle contribute to a healthier future for all. The unseen armor, forged in the crucible of epidemics, continues to offer insights into human survival and the enduring power of life itself.