The Unlettered Genius Who Gave a Nation a Voice: Sequoyah and the Cherokee Syllabary

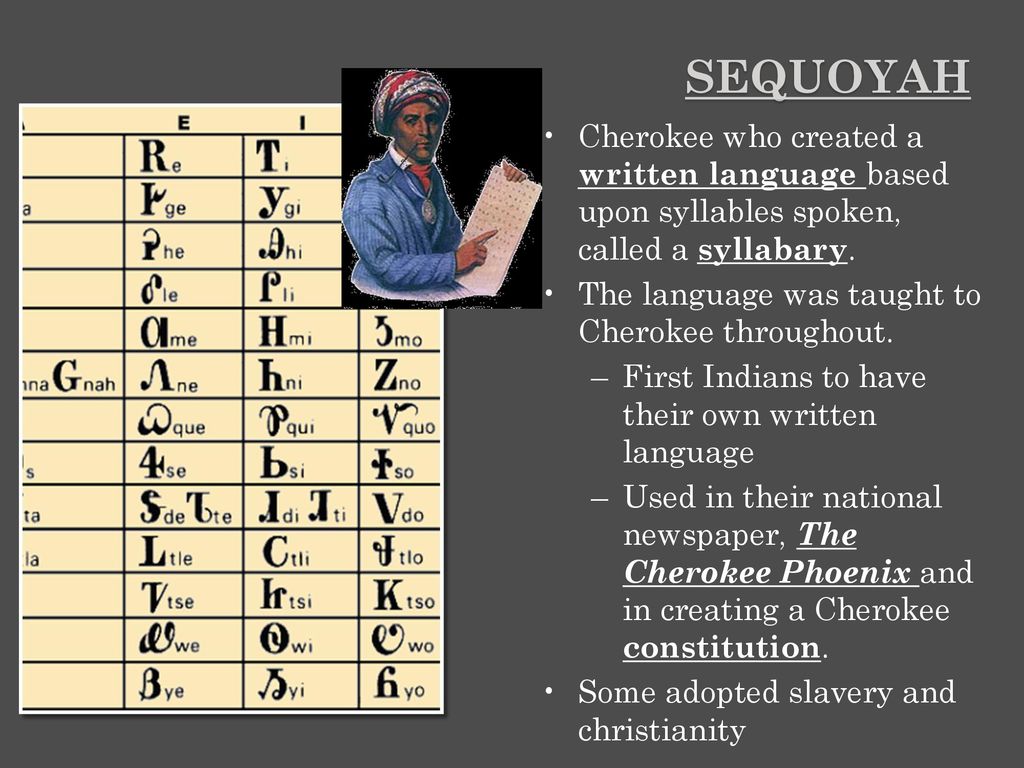

In the annals of human ingenuity, few stories resonate with such profound impact and sheer improbability as that of Sequoyah, a Cherokee man who, despite being entirely unlettered in any language, conceived and perfected a written system for his people. His creation, the Cherokee Syllabary, was not merely an academic achievement; it was a cultural revolution, a tool for sovereignty, and a beacon of resilience that profoundly shaped the destiny of the Cherokee Nation and continues to inspire generations.

Born around 1770 in Tuskegee, Tennessee, to a Cherokee mother and a white father, Sequoyah – known to his white contemporaries as George Gist or Guess – grew up in a world increasingly dominated by the written word of European settlers. He was a skilled silversmith and blacksmith, a tradesman whose hands were accustomed to shaping metal, not letters. Yet, he observed with keen intellect the power wielded by the "talking leaves" of the white man – their ability to communicate across vast distances and generations, to record laws, treaties, and stories. This observation sparked an idea, a singular obsession that would consume more than a decade of his life: to create a similar system for the Cherokee language.

The early 19th century was a tumultuous period for the Cherokee Nation. Pressed by land-hungry settlers and the expanding American republic, the Cherokee were grappling with the existential threat of cultural erosion and forced removal. They were, however, a sophisticated society, having adopted elements of Western governance and agriculture. What they lacked, Sequoyah believed, was a written language – a critical tool for self-governance, education, and cultural preservation in the face of immense external pressure.

Sequoyah’s initial attempts were fraught with difficulty. He first tried to create a logographic system, where each word had its own symbol, much like ancient Chinese. This quickly proved unwieldy, requiring thousands of characters. He experimented with various designs, borrowing, perhaps, the visual forms of English letters, Greek, or Latin characters he might have seen, but assigning them entirely new, Cherokee sounds. His community, and even his family, initially viewed his work with suspicion, seeing it as an eccentricity, or worse, a form of witchcraft. His wife reportedly burned some of his early notes, convinced he was wasting his time.

It was during the War of 1812, while serving with Cherokee warriors allied with Andrew Jackson, that Sequoyah’s conviction solidified. He saw the inefficiency of oral communication in military strategy and the clear advantage of written orders. This experience reinforced his belief that a written language was not a luxury, but a necessity for his people’s survival and advancement.

The breakthrough came when Sequoyah realized that the Cherokee language, while rich in vocabulary, was built upon a relatively small number of recurring syllables. Instead of trying to create a symbol for every word, or every single sound (like an alphabet), he decided to create a symbol for each syllable. This revelation was a stroke of genius. He dedicated himself to this task, often working in isolation, with only his young daughter, Ayoka, to assist him. She would dictate words, and he would carefully note down the corresponding syllables, refining his symbols until he had a comprehensive list.

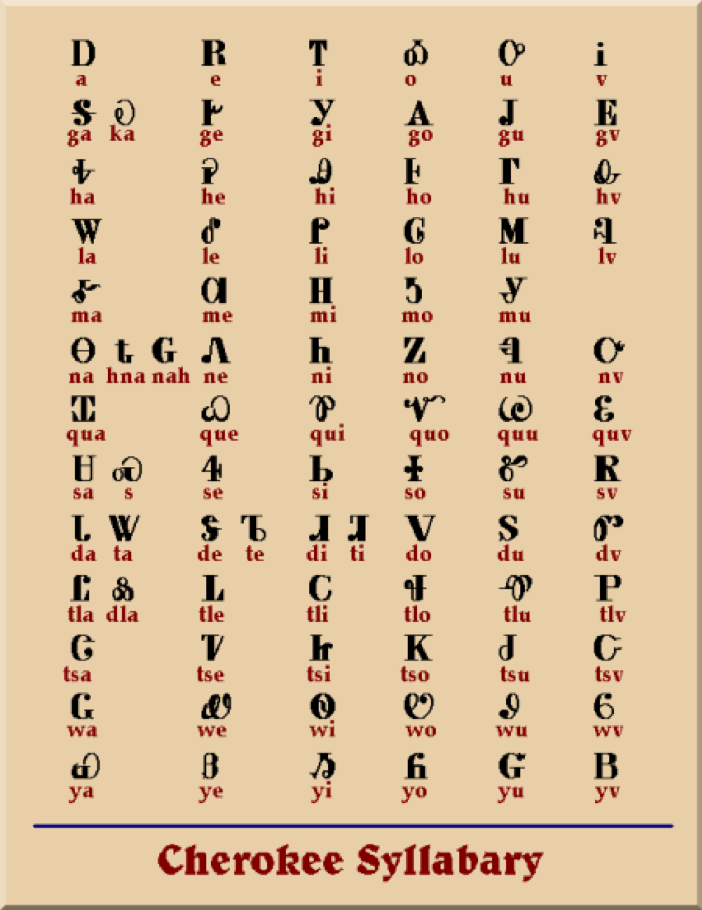

By 1821, after twelve years of relentless effort, Sequoyah had perfected his syllabary. It consisted of 85 (initially 86) distinct characters, each representing a specific syllable. Unlike the English alphabet, which requires users to combine letters to form sounds and words, Sequoyah’s system was elegantly phonetic and remarkably intuitive. Each character always represented the same sound, making it incredibly easy to learn and apply.

The immediate impact was nothing short of miraculous. To prove its efficacy, Sequoyah presented his system to Cherokee leaders. His daughter, Ayoka, and a few others who had learned the syllabary, demonstrated their ability to read and write messages. The skepticism quickly evaporated, replaced by awe and enthusiasm. Within months, thousands of Cherokees began to learn the syllabary. Its simplicity meant that literacy could be achieved in weeks, sometimes even days, rather than the years typically required to master the complexities of the English alphabet.

The adoption rate was unprecedented. Within a decade, it is estimated that the Cherokee Nation achieved a literacy rate that surpassed that of the surrounding white American population. This was a testament not only to the brilliance of Sequoyah’s design but also to the Cherokee people’s deep desire for knowledge and self-determination.

The syllabary became the cornerstone of a Cherokee cultural renaissance. In 1828, a mere seven years after its introduction, the Cherokee Nation established the Cherokee Phoenix, the first newspaper published by Native Americans in the United States. Printed in both Cherokee and English, the Phoenix served as a vital communication tool, disseminating news, laws, and editorials throughout the Nation. It was a powerful symbol of Cherokee sovereignty and their ability to engage with the modern world on their own terms. As Elias Boudinot, the Phoenix‘s first editor, famously wrote, "The great object of the Phoenix is to disseminate useful knowledge among our citizens, and to acquaint them with the transactions of our own country and of the world."

Beyond the newspaper, the syllabary facilitated the writing of the Cherokee Nation’s constitution in 1827, the translation of the Bible and other religious texts, and the creation of schoolbooks. It enabled the codification of their laws, the documentation of their rich oral traditions, and the communication of their political positions to the U.S. government. It fostered a sense of national unity and pride, reinforcing a distinct Cherokee identity in the face of relentless external pressures.

The syllabary’s role became particularly poignant during the tragic period leading up to the forced removal known as the Trail of Tears (1838-1839). Even as the U.S. government, under President Andrew Jackson, pursued a policy of Indian Removal, the Cherokee used their written language to petition, appeal, and articulate their rights. Letters written in the syllabary were sent to Washington, D.C., and circulated among the Cherokee people, serving as a tool of political resistance and a means to document their suffering and protest the injustice. The irony was bitter: a people who had achieved such remarkable intellectual and governmental advancements were still deemed "savages" by those who sought to dispossess them.

Sequoyah himself continued to contribute to his people. He traveled extensively, promoting the syllabary among other Cherokee communities and even attempting to create similar systems for other Native American languages, though with less success. He died in 1843 in present-day Mexico, while on a mission to locate a band of Cherokees who had migrated there years earlier.

The legacy of Sequoyah and his syllabary is immense and enduring. It stands as a powerful testament to the intellectual capacity of indigenous peoples and the universal human drive for communication and self-expression. The syllabary proved that a sophisticated written language could be developed independently of European models, by someone without formal education, simply through observation, logic, and perseverance.

Today, the Cherokee Syllabary remains an integral part of Cherokee identity. While English has become widely spoken, efforts are ongoing to revitalize the Cherokee language, and the syllabary is a central component of these initiatives. It is taught in immersion schools, used in digital contexts, and celebrated as a symbol of cultural resilience. The state of California named its majestic redwood trees, Sequoia sempervirens and Sequoiadendron giganteum, in his honor, a fitting tribute to a man whose monumental achievement provided enduring strength and growth for his people.

Sequoyah’s gift was more than just a set of characters; it was a declaration of intellectual sovereignty, a weapon against assimilation, and a bridge between generations. He unlocked the power of literacy for an entire nation, enabling them to navigate a changing world, preserve their heritage, and articulate their destiny. His story is a powerful reminder that true genius often arises from the most unexpected places, leaving an indelible mark on the course of history and the spirit of a people.