The Unseen Chains: Native American Slavery in Colonial America

For many, the history of slavery in the Americas conjures images of the transatlantic slave trade, of African men, women, and children forcibly brought across the ocean to toil on plantations. This narrative, while undeniably crucial, often overshadows a parallel, equally brutal, and tragically enduring system of human bondage: the enslavement of Native Americans by European colonists. From the earliest days of contact in the Caribbean to the expansion of colonial empires across the North American continent, Indigenous peoples were systematically captured, traded, and exploited, their labor fueling colonial ambitions and their lives irrevocably altered. This hidden history, often relegated to footnotes or entirely omitted, is essential to a complete understanding of the foundations of American society.

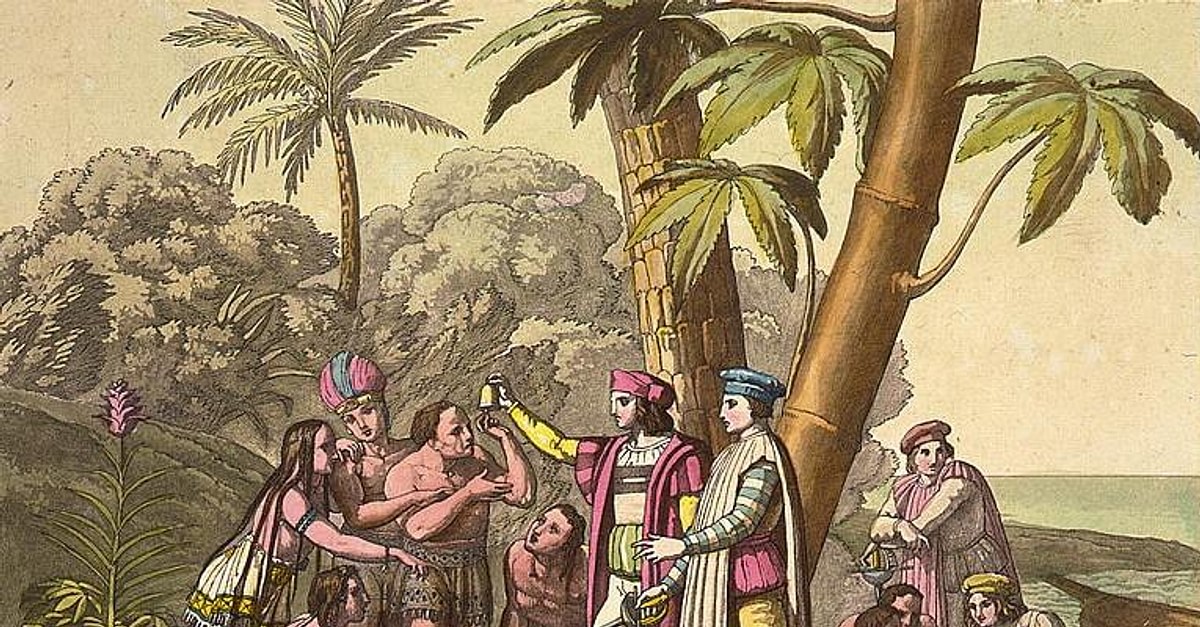

The seeds of Native American enslavement were sown with the very first European arrivals. Christopher Columbus, upon landing in the Caribbean in 1492, quickly realized the potential for exploiting the Indigenous Taíno people. His initial reports to the Spanish crown spoke not only of gold but also of "slaves, as many as they shall order." Within a few years, the Taíno population, unaccustomed to European diseases and brutal forced labor, was decimated. The Spanish implemented the encomienda system, a grant of Indigenous labor and tribute to Spanish colonists, which was effectively a system of slavery. Though theoretically designed to protect and Christianize Native populations, in practice, it led to horrific abuses, with Natives forced to mine gold, cultivate crops, and serve Spanish masters under threat of violence.

Bartolomé de las Casas, a Dominican friar and former encomendero himself, became a fierce critic of this system, detailing the atrocities committed against the Indigenous peoples in his influential work, A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies (1552). He wrote, "The cause why the Christians have destroyed and made an end of so many millions of souls, has been only to get, as their ultimate end, gold." While his advocacy led to some reforms, like the New Laws of 1542, the practice of Indigenous enslavement continued and adapted, evolving into the repartimiento system, which still demanded forced labor, albeit with some nominal regulations.

As European powers expanded their reach into North America, the English, French, and Dutch also quickly adopted and adapted the practice of Native American enslavement. For the English colonists, particularly in the nascent settlements of Virginia and New England, the rationale for enslavement was often rooted in notions of "just war" and perceived Native "savagery." Conflict over land and resources became a convenient pretext for capturing and enslaving Indigenous populations.

One of the most prominent early examples occurred during the Pequot War of 1637 in New England. Following the infamous Mystic Massacre, where English and allied Native forces burned a Pequot fort, killing hundreds, the surviving Pequots were rounded up. Many were executed, but hundreds more—women and children primarily—were enslaved. Some were distributed among colonial households in New England, while others were shipped to the West Indies, particularly Barbados, to be exchanged for African slaves or rum. This established a critical precedent: military victory conferred the right to enslave.

This pattern repeated itself during King Philip’s War (1675-1678), a devastating conflict between New England colonists and a confederation of Native American tribes led by Metacomet (known to the English as King Philip). Thousands of Native Americans were captured during and after this war, with many sold into slavery both locally and overseas. The scale of this trade was significant. Historian Alan Gallay, in his seminal work The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South 1670-1717, estimates that between 1670 and 1715, English colonists in the American South enslaved and exported tens of thousands, possibly as many as 50,000, Native Americans to other colonies in the Americas and Europe.

The Carolina colony, founded in 1670, became a major hub for this trade. Settlers, often in alliance with certain Native groups like the Westos and later the Yamasee, actively raided other tribes—such as the Apalachee, Timucua, and Choctaw—for captives. These enslaved individuals were then put to work on plantations growing rice and indigo, or shipped to the Caribbean sugar islands. The demand for Native slaves was so high that it fueled a cycle of inter-tribal warfare, as European traders incentivized Native allies with guns and goods in exchange for captives. This strategy cleverly divided and weakened Indigenous resistance, while providing a constant supply of forced labor.

The mechanisms of Native American enslavement were varied and insidious:

- Warfare: As seen in the Pequot and King Philip’s Wars, military defeat often meant enslavement for survivors.

- Debt Peonage: European traders would extend credit to Native communities for goods like guns and tools. When debts could not be paid, individuals, often women and children, were seized as collateral and enslaved.

- Criminal Punishment: Colonial courts would sentence Native Americans convicted of crimes (sometimes minor offenses or even trumped-up charges) to servitude.

- Exploitation of Existing Practices: Some Native societies had forms of captive-taking or temporary servitude, particularly for war captives. Europeans exacerbated and transformed these practices into chattel slavery, a permanent, hereditary, and racialized system fundamentally different from Indigenous traditions.

- Child Abduction: Many Native children were simply kidnapped, either to serve as domestic laborers or to be "adopted" into colonial households and "civilized," effectively losing their identity and freedom.

The conditions for enslaved Native Americans were horrific. They faced forced labor in fields, mines, homes, and logging camps. Disease, particularly European pathogens like smallpox and measles, ravaged populations already weakened by malnutrition and violence. Physical abuse, sexual exploitation, and the deliberate destruction of cultural practices were common. Families were torn apart, with individuals sold to different owners or shipped to distant lands, ensuring the permanent severing of kinship ties.

Despite the overwhelming odds, Native Americans resisted. They ran away, often seeking refuge in remote areas or with allied tribes. They formed maroon communities, sometimes alongside escaped African slaves, particularly in places like Florida (the Seminoles are a prime example of such a blended community). They also engaged in overt rebellion. The Pueblo Revolt of 1680 in New Mexico, where a coordinated uprising led by Popé expelled the Spanish for over a decade, stands as one of the most successful acts of Indigenous resistance against colonial oppression, driven in part by the brutal encomienda and repartimiento systems.

Over time, particularly by the early 18th century, the demand for Native American slaves began to wane, replaced largely by African chattel slavery. Several factors contributed to this "Great Replacement":

- Disease: Native populations, lacking immunity to European diseases, suffered catastrophic declines, making them a less reliable long-term labor source.

- Familiarity with Terrain: Enslaved Native Americans often had a deep knowledge of the local landscape, making escape easier and more frequent.

- Political Instability: The constant raiding for Native slaves often provoked widespread inter-tribal warfare and direct conflict with colonists, threatening colonial stability. As colonial settlements expanded, it became politically expedient to cultivate alliances with some Native groups against others, and a widespread Native slave trade complicated these alliances.

- Economic Viability of African Slave Trade: The transatlantic African slave trade was robust, offering a seemingly inexhaustible supply of enslaved people who were far from home, unfamiliar with the land, and identifiable by race, making them easier to control and track.

However, the shift was not immediate or absolute. In many regions, Native American slavery continued well into the 18th and even 19th centuries, often existing alongside and intertwining with African slavery. Intermarriage between enslaved Africans and Native Americans was common, leading to a complex legacy where many individuals have both African and Indigenous ancestry, further complicating the historical narrative.

The legacy of Native American slavery is profound yet often obscured. Its erasure from mainstream historical accounts is due to several factors: the overwhelming focus on the transatlantic slave trade, the convenient narrative of Indigenous "disappearance" or "conquest," and a general reluctance to confront the full brutality of colonial expansion. Yet, this history shaped demographics, contributed to the destruction of numerous Native nations, and laid foundational economic and social structures in colonial America.

Understanding this history is not merely an academic exercise; it is crucial for comprehending contemporary issues of racial inequality, land rights, and the ongoing struggles for justice faced by Indigenous communities today. The unseen chains of Native American slavery represent a vital, often painful, chapter in American history that demands to be acknowledged, studied, and remembered, ensuring that the full scope of colonial brutality and Indigenous resilience is finally brought into the light.